|

| ||||||

Context

Phonology

Morphology

Verbs • Pronouns • Numbers • Derivational morphology

Syntax

Parameter order • Noun phrases • Adjectives • Conjunctions • Locative verbs • Questions • Complex sentences

Transformations

Focus • Subordination • Nominalization • Causative • VP Anaphor • Gapping • Clefting • Light verbs

Semantic fields

Time • Measures • Names • Letters

Examples • Inside and Outside • Shall we elope?

Sound changes

Borrowings

Lexicon

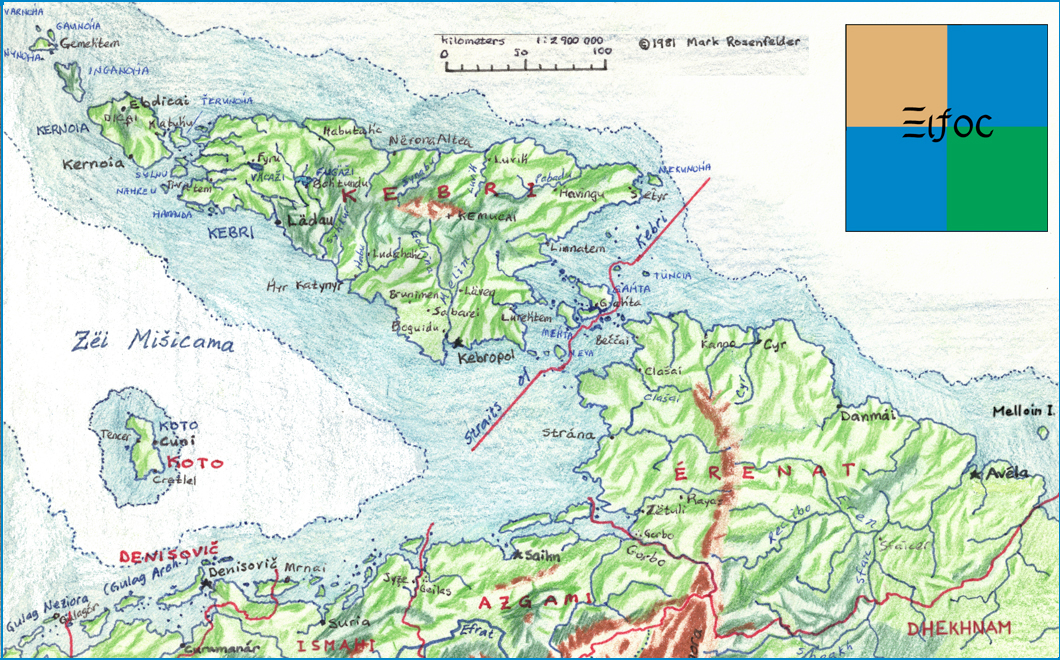

You can decipher the map names using the lexicon.

The map shows borders as of Z.E. 3480.

--Mark Rosenfelder

The first human states in the Plain were Monkhayic: Como and Meťaiu on the upper Svetla, established about Z.E. -1150. By the time they appeared, men had lived in the Plain for twenty thousand years, and the Monkhayic peoples were divided into dozens of mutually incompatible languages.

Civilization and trade spread the prestigious dialects of the cities, and just before the Eastern invasion we are aware of three major speech varieties: that of Okiami and Meťaiu in the south, that of Davur along the lower Svetla, and that of Agimbea and Newor along the Serea and the Mišicama littoral.

The Easterners pushed the Monkhayic peoples (those who were not absorbed) north and east (-375). Refugees from Davur established the kingdom of Davrio on Kebri.

Most of these lands were conquered by Munkhâsh (440), except for the littoral (reorganized as Leziunea) and Kebri.

The continental Monkhayic peoples (and, for about two centuries, even Kebri) were incorporated into the Caďinorian empire as it pushed back and ultimately destroyed Munkhâsh (1667), and though the Monkhayic languages persisted throughout the entire classical area, colonization and Caďinorization eventually replaced them everywhere except two areas, Kebri (plus some regions of Érenat and, till recently, the island of Koto) and Monkhay, the mountainous southwestern corner of Dhekhnam.

The relationship between Kebreni and Monkhayu (both the languages and the peoples) has been obscured by long isolation. In addition, Kebreni has been highly influenced by Caďinor, Ismaîn, and Verdurian, and has borrowed from languages further afield, the Kebreni being great seafarers; while Monkhayu is heavily influenced by Dhekhnami, Caizuran, and Sarroc.

'Monkhayu', which has given its name to the language family, simply means 'the people'; compare Kebreni neḣada.

This document describes the standard Kebreni of the 3400s, in particular that of Kebropol. A separate page on modern Kebreni and its variant in Śaidahami will come later. The lexicon covers both versions; hopefully it will be clear that terms like “quantum mechanics” were not used in the 3400s.

Some of the more notable features of Kebreni:

Following Verdurian scholars, we will call it Meťaiun, after the state of Meťaiu— although the language of pre-invasion Meťaiu was actually a southern Monkhayic language.

This is certainly the most rickety of the ancient languages presented on this website, not excluding proto-Eastern. To begin with, there are no direct ancient attestations; the Monkhayic peoples were illiterate, and remained so till the Caďinorians conquered them. The problem is compounded by the extreme distance between Monkhayu and Kebreni; only a few hundred cognates can be identified.

Our sources for Meťaiun are as follows:

Meťaiun may be taken as an idealized form of the Monkhayic language of Kebri and the littoral, some time before the Munkhâshi invasion. I say ‘idealized’ because none of our sources are completely satisfactory. The Caďinorians were not linguists, and adapted the Monkhayic words to the sounds of Caďinor in order to write them down; while the reconstructions are biased toward the eastern area. Still, the overlap of the two methods is large and reassuring, and where divergences are systematic they can be taken as belonging to western and eastern dialects of Meťaiun.

Kebreni is written using the Verdurian alphabet, using the letters shown. The consonants are as follows:

labial dental palatal velar glottal stops p b

p bt d

t dc

ck g

k gfricatives f v

f vť s z

† s zḣ ś ź

… ß #h

hnasals m

mn

nliquids l r

l r

c is a true palatal stop /c/, pronounced by touching the tongue to the top of the palate. If you can’t do it, you can substitute [tʃ]. Verdurian speakers should not confuse it with [k].

k is pronounced like Verdurian c c /k/, not like its k k /q/. Kebreni has sensibly used Caďinor's two back stop symbols for two points of articulation, but the points are moved forward one step.

ť is the same as the th /θ/ in English thin, the unvoiced version of Verdurian ď ∂.

ś, though it's written using the Verdurian š ß, is a dorso-prepalatal fricative [ɕ], the same as Polish ś or Chinese x. One recipe for producing it is to start with a sh [ʃ] and add more palatal friction to it— say sh, think [ç]. ź is the voiced equivalent.

The h is pronounced as in English (and Old Verdurian), while ḣ is a palatal fricative /ç/, as in German ich. h must be pronounced word-finally (e.g. sih), but not before a consonant (sihzar).

ŋ is sometimes considered a phoneme in Kebreni; it's written ng, as in ingarei. Some dialects say [ŋg] instead.

Doubled consonants (as in linna ‘lord’) are drawn out, as in English pen knife, not penny.

The vowels:

y is a mid vowel, IPA [ɨ], right between i and u. Verdurians mispronounce it as ü, which at least is better than [i]. Kebreni u is a very back vowel (as opposed to English where it is somewhat fronted).

front central back high i

iy

yu

umid e

eo

olow a

a

e o have a wide phonetic range, but it’s safe to pronounce them [ɛ o].

Vowels can adjoin; there is no good case for considering these separate phonemes. Long aa is often written ä ä, as in Verdurian.

Stress is placed on the last syllable if it ends in a consonant, otherwise on the second-to-last vowel: Kébri, Kebropól, paḣár, Leléc, śaída, nizýru, Raazám, mýgu, paúśte, kulséu, ingaréi. Since stress is completely predictable, it is never indicated orthographically.

Kebreni is a syllable-timed language— one where each syllable takes up an equal amount of time— rather than a stress-timed one like English, where stresses occur at roughly equal intervals. Unstressed syllables in Kebreni retain their clear vowel sounds.

The sounds of Meťaiun are reconstructed as follows:

labial dental palatal velar vowels stops p t k i u b d g fricatives f ť s č ȟ e o v z j γ nasals m n a liquids l r semivowel w

This schema should be viewed as our best guess; it is certainly wrong in spots, and phonetic interpretations are quite uncertain.

We have little idea how č was pronounced. The Kebreni reflex is ś. We use č because this is its reflex in Verdurian names inherited from Meťaiun. In Caďinor it was usually written t, tr, or ts, suggesting a palatal stop or affricate. Note also Cad. atrabion ‘emperor‘ > *ačabion > aźban.

In addition, inflection is accomplished by vowel interchange, vowel change, and infixing, not by affixation.

The citation form of the verb is the imperfective:

kanu I see, you see, he was seeing...

diru I work, you work, he was working...

sudy I am called, you are called...

The final -u is not part of the root; it's a grammatical ending. It dissimilates to -y when the last vowel of the root is u, as in sudy.

To form the perfective you switch the last two vowels. (This relationship holds for all the other forms described below, as well.)

kuna I have seen, I saw...

duri I have worked, you worked...

sydu I was once called...

Perfective forms are used for completed actions, no matter what time they occur. Thus you'd use the imperfect diru for 'I was working', because you weren't done yet; and the perfective kuna for 'I will read it', if you mean you'll read it and finish.

An explicit time may always be indicated with adverbs:

Note that Kebreni transitive or ditransitive verbs, used with one less noun phrase, express a passive meaning. ThusPaḣar kanu pol.

Tomorrow you will see the city.

Paḣar kuna pol.

Tomorrow you will have seen (everything in) the city.

Melaḣ

kuna neku.

The king saw the cat.

Nekukuna .

The cat was seen.Nyne

ḣouźi aisel. The girl lost the key.

Aiselḣouzi . The key is lost.Gymu

sudy kulseu 'Ḣulo'.

We call the commander 'Idiot'.

Kulseusudy 'Ḣulo'.

The commander is called 'Idiot'.

Schematically:

NP Vo NP = S V O

NP Vo = O V

NP Voo NP NP = S V O O

NP Voo NP = O V O

Some English verbs work this way as well; but all Kebreni verbs do.

Falte śenen

truśe lyḣ. Your boy broke the window.

Lyḣtruśe . The window broke.

To form the volitional, add an initial e, voice the initial consonant (if any), then switch the first two vowels (that is, the added e- plus what was the first vowel of the root). A final -y returns to -u.

agenu I intend to see, I will see, see! (volitional, uncompleted action)

agune I intended to see, I will have seen (volitional, completed action)ideru I intend to work, I will see, work!

idure I intended to work, I will have worked...uzedu I intend to call, I intend to be called...

uzude I intended to call / no longer be called...

The volitional forms emphasize that the agent consciously intends the action (imperfective) or the result (perfective).

Pucso mabu.

I kicked the dog (perhaps accidentally).Obucse mabu.

I kicked the dog (on purpose).

It is frequently used for a future event (lahu 'come' → alehu 'I will come'), and by extension as an imperative: alehu 'come!' Neither of these extensions is permitted with nonhuman subjects.

There is no word for 'want' as an independent lexical item; some volitional expression must be substituted. Often in fact this is agenu 'want to see', but other verbs are used as appropriate:

If the verb begins with a vowel, insert an h before the vowel switch: adnedu 'I added it' → ahednedu 'I added it on purpose'. (Eśu 'to not be', discussed later, inserts v instead, for historical reasons.)Impuźeu

agenu bonnezi!

The publisher wants (lit. wants-to-see) the story!Linna

ezeḣepu gembadi?

Does His Lordship want (lit. want-to-eat) breakfast?

karynu I see, you see, he sees (uncompleted action)

kurina I have seen, you've seen, he's seen (completed action)agerynu I intend to see, I will see, see! (volitional, uncompleted action)

agurine I intended to see, I will have seen (volitional, completed action)

Polite forms express deference toward a superior, or politeness to an equal. They are used with nobles and royalty, employers, military superiors, parents, in-laws, teachers, and so on. In addition the middle and upper classes use it with each other; but man and wife, siblings or cousins, or very close friends do not.

Ḣem

cyryru ? Do I know you, sir?Alerihu ! Please come!

Note that the politeness applies to the listener, not to the referent.

Kulseu, falaute mabu furina<; ne…at obucrise.

Kulseu, falaute mabufurina ; neḣatobucrise .

commander / you-SUB dog die-PERF-POL / man kick-PERF-POL

Commander, your dog is dead; a man kicked (it).

Polite forms are made by inserting -ri- within the verb root, before the last consonant; -ry- if the vowel in the next syllable is a u. The infix may divide a consonant cluster: kulsu 'command' → kulrysu.

In addition there are a few suppletive forms; e.g. badu 'eat' has the polite form sehepu; tasu 'do' has the polite form soru, and so on. (Do not add -ri- to the suppletive forms; they are already polite.)

The benefactive implies that the given action benefits the speaker in some way:

keni someone sees, to my benefit

deri someone works for me

sidi someone is called, and it helps or flatters me

syťi someone provides to me

It is formed by fronting the stem vowel (a → e, o →e; u → y, y → i, i → e, e unchanged) and changing the final -u to -i. The perfective, volitional, and polite forms are formed according to the usual rules.

The stem vowel is the last vowel of the root; e.g. pansyru 'someone kisses' → pansiri 'someone kisses me'. (Verbs with stem y, like this one, have identical perfective and imperfective.)

To indicate that the action was performed for the benefit of the listener, the infix -ni- is added before the final consonant of the root:

kenini someone sees, to your benefit

deniri someone works for you

Compare:

Ḣazum diru keda. Hazum is working on the house.

Ḣazumderi keda. Hazum is working on my house.

Ḣazumdeniri keda. Hazum is working on your house.Kulseu nuzi melaḣ. The commander spoke to the King. (from nizu, speak)

Kulseunize melaḣ. The commander spoke to the King on my behalf.

Kulseuninize melaḣ. The commander spoke to the King on your behalf.

The antibenefactive implies that the given action harmed the speaker in some way. It's very common in the mouths of Kebrenis and essential for mastering colloquial speech.

kona someone sees, to my loss

dyra someone works against me

soda someone is called, and it harms or insults me

suťa someone provides at my expensekano someone saw, has seen, to my loss

dary someone worked against meadery someone purposely worked against me

oseda they purposely call him that to spite meloriha someone is coming to harm me (polite form)

It is formed by backing the stem vowel (a → o, e → o, i → y; y → u, u → o, o unchanged) and changing the final -u to -a. The perfective, volitional, and polite forms are formed according to the usual rules.

Mabufano . The dog went and died on me.

Ḣemdyra . I'm killing myself by working.Kona hem. He watched me (in order to hurt me); he's spied on me.Obeka . Oh, fuck me.

Again, -ni- can be infixed to indicate that the action was performed to the harm of the listener.

Kulseunyniza . The commander is speaking against you.

Lelecpocnisa ? Is Lelec kicking you?

The subordinating form is used when there is another verb in the sentence. It's formed by moving the final vowel of the verb before the final consonant and adding -te. A labial stop becomes dental and a voiced stop becomes unvoiced before the -te (so m → n, p/b/d → t, g → c, z → s, etc.).

kanu 'see' → kaunte 'seeing'

diru 'work' → diurte 'working'

kulsy 'command' → kulyste 'commanding'

mimu 'deal' → miunte 'dealing'

ciḣcu 'praise' → ciḣucte 'praising'

This form has several uses. One is with auxiliary verbs, or any verb which takes another verb as a possible object. The -te form appears before the main verb, and after its objects:

Mela… kaunte elecu.

Melaḣkaunte elecu.

king seeing VOL-able

The king is able to see you.Kulseu gorkreha kaunte maru.

Kulseu gorkrehakaunte maru.

commander ledger seeing be.probable

The commander is probably reading the ledger.Tarautte …ilu?

Tarautte ḣilu?

dancing like

Do you like to dance?Úem diurte luha.

Ḣemdiurte luha.

I working come-PERF

I came (in order) to work.

The negative in Kebreni is an auxiliary verb, eśu (polite natu):

Úem Úazum cyurte eßu.

Ḣem Ḣazumcyurte eśu .

I Hazum knowing not.be

I don't know Hazum.Úazum kulseu kriu…te uße.

Ḣazum kulseukriuḣte uśe .

Hauzm commander killing not.be-PERF

Hazum won't kill the commander tomorrow.Pa…ar lauhte natu?

Paḣarlauhte natu ?

tomorrow coming not.POL

Aren't you coming tomorrow? (polite)

Note that volitional, politeness, and aspect inflections normally apply only to the main verb. One can make such finicky distinctions as the following--

diurte lahu was/is coming to be working

diurte luha came to be working

duirte lahu was/is coming to work (and finish)

duirte luha came to work (and finish)

diurte alehu is intending to come to work

iderute lahu is coming intending to work

—but these are rare even in writing; normally only the base form (i.e. diurte) is used, and inflections are applied only to the auxiliary. Semantically, they are considered to apply to the auxiliary + verb combination— e.g. for diurte alehu the intention is taken to apply to both the coming and the working; while for diurte luha the entire action— coming to work— is taken as being completed.

Another usage of the -te form is as a gerund or modifier. The subordinated verb suggests the manner in which the main action was performed, or simply names a following or resulting action.

Kulseu kaunte nuzi.

Kulseukaunte nuzi.

commander watching speak-PERF

The commander spoke watchfully.Nyne pabautte taradu.

Nynepabautte taradu.

girl laughting dance-PERF

The girl was laughing and dancing.ˇazu mabu kri…ute pucso.

Ťazu mabukriḣute pucso.

they dog killing kick-PERF

They kicked the dog to death.Úulo ci…ḣucte diurte eßu.

Ḣulociḣucte diurte eśu.

food praising working not-IMPF

The fool works without praising (God).

Finally -te is used to form relative clauses. In this usage volitional, aspect, and effect inflections (but not politeness infixes) can be applied to the subordinating form. Note that the clause precedes the modified noun.

Neḣat duri keda.

Neḣat duri keda.

The man worked on the house →Diurte keda ne…at alehu pahar.

[Diurte keda] neḣat alehu pahar.

[work-SUB house] man come-VOL tomorrow

The man [who worked on the house] will come tomorrow.Kulseu nazy ne…at.

Kulseu nazy neḣat.

The commander spoke against me to the man →Kulseu nayste ne…at sudy Kalum.

[Kulseu nayste] neḣat sudy Kalum.

[commander spoke-ANTIB-SUB] man name Kalum

The man [the commander spoke to against me] is named Kalum.Mela… tigu nyne.

Melaḣ tigu nyne.

The king is screwing the girl →Mela… tiugte nyne …ilu …ente mabu

[Melaḣ tiugte] nyne ḣilu ḣente mabu.

[king screw-SUB] girl like I-SUB dog

The girl [the king is screwing] is fond of my dog.

There is no relativizing pronoun. Note that if the subordinated verb is preceded by a subject, as in the last two sentences, the head of the clause must be taken as a direct or indirect object; if the verb begins the clause, as in the first example, the head must be the subject of the clause. Schematically:

NP Vte NP = [S V] O

Vte NP NP = [V O] S

If the head noun refers to a place or time, the phrase is equivalent to a when or where clause in English— again, these pronouns do not appear in Kebreni:

[vaac mygu moiutte] ha…c

[vaac mygu moiutte] haḣc

[blue ox find-SUB] valley

the valley [where the blue ox was found][pocuste mela…] re

[pocuste melaḣ] re

[kick-SUB king day

the day [when I kicked the King]

Ellipses indicate that variations (the imperfective and the two volitional forms) are being left out.

| 'see' | 'work' | 'call' | 'laugh' | 'kick' | 'command' | 'not' | ||

| Neutral | imperfective | kanu | diru | sudy | pabadu | pocsu | kulsy | eśu |

| perfective | kuna | duri | sydu | pabuda | pucso | kylsu | uśe | |

| volitional imp. | agenu | ideru | uzedu | abebadu | obecsu | ugelsu | eveśu | |

| volitional perf. | agune | idure | uzude | abebuda | obucse | ugulse | evuśe | |

| polite imp. | karynu | diryru | suridy | pabarydu | pocrysu | kulrisy | natu | |

| polite perf. | kurina | duriri | syrydu | paburida | pucriso | kylrysu | nuta | |

| vol. pol. imp. | agerynu | ideryru | uzerydu | abebarydu | obecrysu | ugelrysu | anetu | |

| vol. pol. perf. | agurine | idurire | uzuride | abeburida | obucrise | ugulrise | anute | |

| Benef. | benef. imp. | keni | deri | sydi | pabedi | pecsi | kylsi | eśi |

| benef. perf. | kine | dire | sidy | pabide | picse | kilsy | iśe | |

| vol. ben. imp. | egeni | ederi | yzedi | abebedi | ebecsi | ygelsi | eveśi | |

| vol. ben. perf. | egine | edire | yzide | abebide | ebicse | ygilse | eviśe | |

| benef. polite | kerini... | deriri... | syridi... | paberidi... | pecrisi... | kylrisi... | neti... | |

| benef. 'you' | kenini... | deniri... | synidi... | pabenidi... | pecnisi... | kylnisi... | eniśi... | |

| Antib. | antib. imp. | kona | dyra | soda | paboda | pocsa | kolsa | ośa |

| antib. perf. | kano | dary | sado | pabado | pacso | kalso | aśo | |

| vol. antib. imp. | ogena | ydera | ozeda | abeboda | obecsa | ogelsa | oveśa | |

| vol. antib. perf. | ogane | ydare | ozade | abebado | obacse | ogalse | ovaśe | |

| antib. polite | korina... | dyrira... | sorida... | paborida... | pocrisa... | kolrisa... | nota... | |

| Subord. | subordinating | kaunte | diurte | suytte | pabautte | pocuste | kulyste | euśte |

| subord. perf. | kuante | duirte | syutte | pabuatte | pucoste | kyluste | ueśte | |

| sub. vol. imp. | ageunte | ideurte | uzeytte | abebautte | obecuste | ugeluste | eveuśte | |

| sub. vol. perf. | aguente | iduerte | uzyette | abebuatte | obuceste | uguleste | evueśte | |

| Deriv. | one who does | kaneu | direu | sudeu | pabadeu | pocseu | kulseu | |

| 'participle' | kaina | diera | suida | pabaida | pocisa | kulisa | ||

| action | kani | deri | sodi | pabadi | pacsi | kolsi |

pejorative ordinary deferential person sing plural sing plural sing plural 1 (I, we) cin źum ḣem gymu — 2 (you) kuḣ fal falau 3 (he, she, it, they) vuḣ ťaḣ ťaza vep vybu

There are three sets of pronouns in Kebreni, which imply contempt, neutrality, or deference toward the referent.

The pejorative first person forms (cin, źum) are humilifics, used to refer to oneself when speaking with a superior; the remaining pejorative forms (kuḣ and vuḣ— one does not bother with any number distinction) are used to refer to those of lower classes (or, of course, to insult someone by referring to them as inferiors).

The deferential second person form falau is an honorific, used to refer to a listener or listeners who are social superiors; its use roughly correlates with the use of the polite forms of verbs. Note that the third person forms (vep, vybu) express deference to the person referred to, not (unlike polite verbs) to the listener. There are no deferential first-person pronouns.

For all of these pronouns, possessive forms can be made by adding -te (which forces a preceding labial stop to assimilate): ḣente 'my (ordinary)', falaute 'your (deferential)', vuḣte 'his/her/its/theirs (pejorative)'.

It must be emphasized that pronouns are optional, and indeed to be avoided, in Kebreni. They are used only when necessary for clarity. For direct address, in fact, it's preferable to use honorifics and titles:

Linna, agenu gembadi?

Linna, agenu gembadi?

lord / eat-VOL breakfast

Lord, [do you] want [your] breakfast?

‘This’ and ‘that’, as adjectives, are gem and kuri (the relation to ‘one’ and ‘two’ is obvious, but the direction of semantic borrowing is not!): gem nyne ‘this woman’, kuri palaźnu ‘that thorn-bush’.

As standalone pronouns these become gente ‘this one’ and kurite ‘that one'. (This is actually a standard nominalizing use of the clitic -te with adjectives.)

Myra ‘here’, tomo ‘there’, źada ‘now’ and bada ‘then’ function as adverbs.

The standard interrogative anaphora are:

śava ßava who, what śete ßete which (of what quality) aśeve aßeve why ciźe ci#e how, in what way śanu ßanu where (locative verb) śere ßere when bigynte bigynte how much, how many

Unlike in English, the interrogative anaphora cannot be used in relative clauses. Subordinated clauses usually have no explicit subordinator at all. See Complex sentences below for examples.

Quantifiers are ordinary adjectives, and like any adjectives are nominalized with -te.

fyn fyn none fynte fynte nothing, no one biha biha some, any bihate bihate something, someone, anything, anyone kum kum many, much kunte kunte many things, many people orat orat all, every oratte oratte everything, everyone

There are no words meaning ‘everywhere’, ‘sometime’, and so on; instead one uses expressions like biha re ‘some day’, orat hami ‘every land’, fyn haḣcte zani ‘in every valley’, etc.

1 grem (related to 'this') 2 kuri (related to 'that') 3 dama 4 γakaȟ ('almost (a hand)') 5 amua ('hand') 6 migrem amua ('with-one hand')... 9 γakaȟ kuri ('almost two (hands)') 10 kuramua ('two hands') 11 poc pinaȟ ('down to the feet') 12 mikuri kuramua ('two hands with two') 14 mipoc kuramua ('two hands with a foot') 15 migrem mipoc kuramua ('two hands with a foot with one') 18 oranda neȟad ('entire man') 324 dikumi (related to kumi 'many') 5832 ťeleť

Under the influence of Cuêzi and Caďinor, a decimal system was adopted; but the Kebreni numbers from 1 to 19 still show their origins in the Meťaiun system:

The numbers from 21 to 99 are formed on the model [tens] kram [digits]-ai: 21 = kur kram gemai, 37 = dam kram migurai. In fast counting, kram is omitted.

1 gem 11 pinaḣ 2 kur 12 migram 3 dam 13 midakram 4 hak 14 mipoc 5 amma 15 mipokemai 6 migem 16 mipokurai 7 migur 17 hakraida 8 midam 18 raida 9 hakur 19 raigemai 10 kram 20 kur kram

It's still possible to count by 18s: raida, kuraida, dam raida... This can be a nice way to hide a price increase: rather than charging 4 alať for ten, you charge 8 alať for eighteen.

dygum (from dikumi) has become the word for 100, while myga '1000' was borrowed from Cuêzi. The same basic model is followed: 487 = hak dygum midam kram migurai, 3480 = dam myga hak dygum midam kramai.

There are two ways of numbering noun phrases: by inserting the number before the noun, or by subordinating the noun and following it with the number:

dam kyr laḣ or kyr laḣtedam

three green fields

The subordinated form is more formal, and is preferred in writing, or with very long numbers.

The suffix -eḣ (-ḣ after vowel) forms ordinal numbers: gemeḣ 'first', raidaḣ 'eighteenth'.

The suffix -nu is used for fractions: kuirnu 1/2, dainnu 1/3, haiknu 1/4, ammanu 1/5, migemnu 1/6, etc.

Arithmetic expressions:

As in Verdurian, multiplication and division are expressed using ordinals. Note the double marking: dam 3 > dameḣ 1/3 > dameḣte.3 + 2 = 5

dam e…c kur zaru amma

dam eḣc kur zaru amma

three and two exist five

3 + 2 = 57 – 2 = 5

migur kur fuuste zaru amma

migur kur fuuste zaru amma

seven two lacking exist five

7 - 2 = 53 ° 4 = 12

dame…te hak zaru migram

dameḣte hak zaru migram

third four exist twelve

3 x 4 = 1212 ^ 4 = 3

migrame…te haiknu zaru dam

migrameḣte haiknu zaru dam

twelfth 1/4 exist twelve

12 / 4 = 3

With adjectives, nominalizations with -gu name the abstract quality; with nouns and verbs, they generally name a countable action, result, or associated entity.

kanu see → kangu vista

boťynu fight → boťengu battle

syh strong → sygu strength

śen honorable → śengu honor

With nouns and verbs, -au (Meť. -adio) is an abstract nominalizer, comparable to our -tion; with adjectives it names an object with the given quality.

adnedu add → adnedau addition

kanu see → kanau vision

maru be probable → marau probability

melaḣ king → melaḣau royalty, kingship

ty round → tyau tube, pipe

For simple actions, a name for an instance of the action can be formed by lowering the last root vowel (i, y → e; e, o → a; u → o, a unchanged) and adding -i:

riḣu count → reḣi count, counting

pocsu kick → pacsi kick

taradu dance → taradi dance

źynu go → źeni departure

kulsy command → kolsi command

The suffix -nu, usually accompanied by raising of the last root vowel (a → e, e → i, o → u, others unchanged) names a concrete thing related to the root object or action.

gyru (Meť. ger-) rise → hernu (Meť. gerno) stair

kam oak → kamnu acorn

muk new → muhnu news

To pluralize a noun, you follow the formula (X)V1C(V2) → (X)V1C[+vcd]V1. The status of pluralization in Kebreni is quite different from languages such as Verdurian and English, where it is obligatory and grammaticalized. It is an optional derivation in Kebreni; it can be thought of as forming a collective noun— ‘a unit formed by more than one X.’

hami land → hama lands, large area, nation

neḣat man → neḣada people

cai (Meť. kiodi) mountain → cadu (Meť. kiodo) mountain range

beź grape → beźe bunch of grapes

lore horse → loro team of horses

-na is an augmentative; -iḣ is a diminutive.

ḣir long → ḣirna very long

siva sand → sivana desert

lezu forest → Lezyna Leziunea = big forestzeveu friend → zeviḣ little friend

tada father → tadiḣ dad

nyne maiden → nyniḣ little girl

-eu names a person who does the action, comes from a place, or has a certain quality:

kulsy command → kulseu commander

taradu dance → taradeu dancer

Verdura Verduria → Verdureu Verdurian

zev loyal → zeveu friend

The Meťaiun equivalent was formed by replacing the final root vowel of the verb with -u- and suffixing -i. This formation is found in a few old words:

γis- cure → γusi (hus) doctor

brin- watch → bruni (brun) shepherd

-ec has about the same meaning, but specifically names a feminine referent. Kebreni is usually not concerned to do so (e.g. melaḣ means both king and queen), but may use -ec in a few cases where the occupation is chiefly female (e.g. maḣec ‘prostitute’) or where it’s desired to refer to a couple without awkwardness— e.g. a dance manual describing a duet may refer to the taradeu and taradec. The suffix is most commonly used to form girls’ names.

lele cute, pretty → Lelec

lezu forest → Lezec

Meťaiun -(γ)umi, whose Kebreni reflex is -um, named someone who lives in a particular place; it's related to γami 'land': thus limiγumi 'highlander'. As a productive prefix, it has been replaced by -eu in Kebreni; but -um is still found in personal names and in inhabitant-names of very old cities:

kal bee → Kalum

śogu ridge → Śogum

Laadau → Laadum person from Laadau

Kaťinaḣ Caďinas → Kaťynum Caďinorian

A manufacturer of something is named with -teu (a reduced form of taseu 'maker'):

nabira ship → nabirateu shipwright

Given a verbal root CVXn, the formula VC[+vcd]VXne names a tool which accomplishes the action, or a substance which exemplifies it (contrast -eu, which is always a person):

paźu cut → abaźe knife

ťanu harm → aťane weapon

treḣ black → etreḣe ink

The suffix -eśa creates a concrete nominalization of an adjective: an object having the quality named by the adjective:

gem one → geneśa primacy (among interested parties), lien

ḣir long → ḣireśa street

-arei names a place:

suťy provide → suťarei store

lore horse → lodarei stable (with dissimilation)

nizu speak → nizarei forum

The proprietor or manager of such a place is named with the suffix -areu (unless there already exists a simple form with -eu, e.g. suťeu 'provider, storekeeper'):

ingarei tavern → ingareu tavernkeeper

From toponyms and nobles' names we learn of a vowel-harmonizing honorific prefix me- in Meťaiun: Monȟado (Monkhayu), Mičiaγama (Mišicama), meneula (Menla), meleȟ 'king', myvun 'leader'. It's also seen in Meťaiu, Meuna, Mevost, Metōre. The prefix is not seen in modern Kebreni, and usually disappears in cognates: Śahama 'Mišicama', neḣada 'the people'.

The subordinator -te, attached to a single word, in effect turns it into an adjective.

keda house → kedate domestic

neḣada people → neḣadate popular

diru work → dirte relating to work

Attached to expressions referring to people, including pronouns, it serves as a genitive:

falau you → falaute your

nyne maiden → nynete maiden’s

Verdureu Verdurian → Verdureute Verdurian’s

An adjective related to a geographic expression is formed with -en:

Kebri Kebreni → kebren Kebreni

Ernaituḣ Érenat → ernaituhen Érenati

The infix -n- + final -(y)r gives an adjective meaning 'having the quality of X' or 'liable to X':

boḣtu water → bontur wet

men hill → mennyr hilly

ḣulo idiot → ḣunlor idiotic

zeveu friend → zevenur friendly

kriḣu kill → krinḣyr murderous

pabadu laugh → pabandyr amusing

The infix -su- gives an adjective meaning 'made of X':

siva sand → sisuva sandy

ḣeda stone → ḣesuda stony

kam oak → kasum oaken

The meaning of an adjective may be intensified by infixing -u- before the last consonant, or diminished by infixing -i-:

ḣir long → ḣiur very long, ḣiir not long

śaida beautiful → śaiuda breathtakingly beautiful

śe small → śei tiny

A similar process can be seen in Meť. nauni 'young man', niune 'young woman' (but it's obscured by sound change in Kebreni: nen, nyne).

-iCa where -C is the final consonant of the root, or -eCa after -i-, means 'that has been Xed'. This sounds like a past participle, but it is never a verbal form, nor can it even be used predicatively; it can only be used to modify a noun, or as a nominalization.

nizu say → nieza spoken

suťy provide → suiťa provisions;

kulsy command → kulisa what is commanded, lexicalized as ‘fleet’

nabru sail → nabira what is sailed, i.e. a ship

The suffix -lecsu (from lecu 'can'), added to a verb, means equally 'that can be verbed' or 'that can verb'; context generally indicates which.

badu eat → badlecsu edible

źaiźigu marry → źaiźiglecsu marriageable, nubile

treśu break → treślecsu breakable

The infix -at-, used to produce antonyms in Meťaiun, is no longer productive:

zewi loyal → zatewi disloyal, treasonous

čiam- aproach → čatiam- move away from

An adjective can be negated with bu- (borrowed from Caďinor):

doḣt correct → budoḣt incorrect

gauryr pure → bugauryr impure

Nouns can be fairly freely converted into verbs by adding -u (replacing a final vowel):

dyrḣi credit (entry) → dyrḣu (enter as a) credit

nabra sail → nabru sail

alat silver coin → aladu spend money

A syntactic alternative, to use the verb tasu 'do', is extremely productive, especially for vague nonce forms:

suťarei store → suťarei tasu shop

zeveu friend → zeveu tasu be friendly

ťiron market → ťiron tasu go to market

The suffix -s- forms verbs with the meaning 'to use X (in the obvious way)' or 'to act like X':

poc foot → pocsu kick

bry eye → brysu keep an eye on

śemu fish → śemsu swim

mygu ox → mycsu haul

The infix -ma- means 'to make X' or 'to acquire X':

syl dark → symalu darken

hazik proud → hazimaku make proud

kur two → kumaru split

śemu fish → śemamu fish

alat silver → alamatu scrounge up cash

Locative verbs can be prefixed to verbs, often with the effect of specifying a direction or purpose for the action. Often an abbreviated form of the locative is used.

ebu be away from + diru work → ebdiru take off work

dynu be above + riḣu count → dyrḣu count as a credit

These expressions derive from a subordinated verb: eupte diru → ebdiru.

See the section on Focus for alternatives.Linna Kalum, gente bo†eneu a#ei#irygu falaute nyni….

Linna Kalum, gente boťeneuaźeiźirygu falaute nyniḣ.

lord Kalum / this soldier VOL-marry-POL your-DEFER daughter-DIM

Lord Kalum, this soldier wants to marry your daughter.Úazum, linna agenu hus.

Ḣazum, linnaagenu hus.

Hazum / lord see-VOL doctor

Ḣazum, the Lord needs a doctor.

Kebreni makes no morphological distinction between direct and indirect objects. One or both can appear after the verb, or be fronted for emphasis. The indirect object follows the direct object if both are given.

Kulseu …uvy ve#a taradeu.

Kulseu ḣuvy veźataradeu .

commander give-PERF bottle dancer

The commander gave the bottle to the dancer.Nyne mugeu …uvy ßemu.

Nyne mugeu ḣuvy śemu.

girl youngster give-PERF fish

The girl was given a fish by the young man.Íemu nyne mu…a.

Śemu nyne muḣa.

fish girl sell-PERF

As for the fish, the girl sold it.

Another way of putting this is that verbs like ḣyvu 'give' are ditransitive in Kebreni, like sudy 'call (someone) (something)'.

Schematically:

NP V NP = S V O

NP NP V = O S V

NP V NP NP = S V O O

NP NP V NP = O S V O

The destination of a verb of movement is not morphologically marked in Kebreni; it's treated as an indirect object.

Linna, #yrynu Laadau.

Linna, źyrynuLaadau .

lord / go-POL Laadau

Lord, we're going to Laadau.Kuri ťani…te ne…at lahu #umte keda?

Kuri ťaniḣte neḣat lahuźumte keda ?

that annoying man come we-SUB house

Is that annoying man coming to our house?Ime#yny ßemu tada.

Imeźynu śemutada .

bring-VOL fish father

Bring a fish to your father.

However, the source of a movement is indicated using a locative verb (discussed below):

Laaven eupte lahu e…c bohru.

Laaven eupte lahu eḣc bohru.

Laaven from-SUB come and stink

They're coming from Laaven and they stink.

Modifiers— including adjectives, numbers, relative clauses and locative expressions— always precede the noun:

kur

mabu two dogs

gem śaida hazigainyne that beautiful and proud maiden

ťaniḣteneḣat an annoying man

kaunte melaḣmabu a dog that looks at a king

sivana śaunteturgul the battalion near the desert

Kebreni's strong modifier-modified order would lead a linguist to suspect that it was once an OV language, which has changed, perhaps, under the influence of Verdurian. The evidence is equivocal; we do not have many actual texts in Meťaiun. However, they do seem to be predominantly SOV.

The root meaning of -te is to reduce an expression to an attribute. It reduces a noun or noun phrase to an adjectival expression, a verbal expression to a subordinate clause.

With a single noun (or pronoun), a -te expression has an adjectival or possessive quality:

falaute gem one of youtadate zevu father's friendneḣadate nizarei the people's forumkedate zivan the inside of the house (lit. the house's inside)

The same can be said of longer expressions that are themselves -te expressions:

falaute gente mygu the ox belonging to one of youKalunte tadate zevu Kalum's father's friendneḣadate nizareite dirau the work of the people's forum

With more complex expressions -te functions like a relative clause:

dama rete ebdiru a three-day holiday; a holiday that's three days longḣulo tauste melaḣ a king who acts like an idiotkeda ziunte te mygu the ox that's in the house

Finally, a -te clause can stand on its own, meaning 'the one(s) which...':

Fal buda Kazumte be#e e…c …em buda Lelecte.

Fal buda Kazumte beźe eḣc ḣem budaLelecte .

you eat-PERF Kazum-SUB grape and I eat-PERF Lelec-SUB

You ate Kazum's grapes and I ate Lelec's.Ru…i Avela… eupte lauhte? ˇa… miry.

RuḣiAvelaḣ eupte lauhte ? Ťaḣ miry.

count-PERF Avéla from-SUB coming / 3s rich

Did you count the one who comes from Avéla? He's rich.

There is no verb 'to be' in Kebreni; the closest equivalent is zaru 'exist, be there'.

Dama gegeu zaru, e…c dama ve#a zaurte eßu.

Dama gegeuzaru , eḣc dama veźazaurte eśu .

three servant exist / and there bottle existing not

(Lit.) Three servants exist, and three bottles do not exist.

There's three servants and three missing bottles.Bo†engu ziunte ci…ica ingarei zura.

Boťengu ziunte ciḣica ingareizura .

Boggola being.in praised tavern exist-PERF

In Boggola there used to be a praiseworthy tavern.

There is no verb 'have' either; zaru with effect inflections serves for this.

Keda, kur gegeu, e…c ßemu zeri.

Keda, kur gegeu, eḣc śemuzeri .

house two servant and fish have-BENEF

I have a house, two servants, and a fish. (Lit, they exist for my benefit.)Lelena lelena nyne zeniri.

Lelena lelena nynezeniri .

cute-AUG cute-AUG girl have-YOU-BENEF

You have a very, very cute daughter. (Lit., she exists for your benefit.)

Negative effect inflections are used when the possession is disadvantageous.

In the third person, the locative verb śamu is used instead:Keda eupte symanlur kangu zora.

Keda eupte symanlur kanguzora .

house from-SUB boring view exist-ANTIB

I have a boring view from my house.Paru ziunte cuka zonira.

Paru ziunte cukazonira .

lip being.in pimple exist-YOU-ANTIB

You have a pimple on your lip.

Lelena nyne ßamu kulseu.

Lelena nyneśamu kulseu.

cute-AUG girl be.around commander

The commander has a very cute daughter. (Lit., she is near him.)

Or you can use possessive expressions, e.g.:

Kulseute pabandyr lore zaru.

Kulseute pabandyr lore zaru.

commander-SUB amusing horse exist

(Lit.) The commander's amusing horse exists.

The commander has an amusing horse.

There is no attributive 'be' at all; to say that X is Y you normally simply adjoin the two noun phrases.

Úente tada be#arei e…c baba taradeu.

Ḣente tada beźarei eḣc baba taradeu.

I-SUB father vintner and mother dancer

My father is a vintner and my mother is a dancer.

To say that X belongs to the class Y, you can use sudy 'be called':

Erankra… sudy kra….

Ebrankraḣ sudy kraḣ.

cinnabar nam mineral

Cinnabar is (lit. is called) a mineral.

To reveal that X is actually Y, one can use the expression X Yai gensu 'X and Y are one'; the opposite can be indicated with kursu 'be two, differ':

Linna, kri…u loreai genrysu.

Linna, kriḣu loreaigenrysu .

lord / killer horse-AND be.one-POL

My lords, the killer is— the horse. (Lit., the killer and the horse are one.)Falte tada e…c taradeu kursu.

Falte tada eḣc taradeukursu .

you-SUB father and dancer be.two

Your father is no dancer. (Lit., your father and a dancer differ.)

Adjectives used attributively appear before the noun, without modification: śaida seť 'a beautiful jewel'; ťaniḣte źem ḣulo 'an annoying old idiot'.

As predicates they are a bit more complicated; in effect they are partially converted into verbs. No copula is used. In the simplest form, the adjective simply appears after the noun, in verbal position:

Kri…eu #em.

Kriḣeuźem .

killer old

The killer is old.

The politeness infix -ri- must be used in the same situations it would be used on a verb:

Falte nyne ßaida.

you-SUB girl beautiful

Falte nyne śaida.

Your daughter is beautiful. (ordinary)Falaute nyne śairida.

Falaute nyneśairida .

you.POL-SUB girl beautiful-POL

Your daughter is beautiful. (polite)

The predication is negated using the auxiliary eśu and the subordinator -te, as with verbs, and other auxiliaries may be used as well:

Gem mabu #ente eßu.

Gem mabuźente eśu .

this dog old not

This dog is not old.Mela… miryte maru.

Melaḣmiryte maru .

king rich be.probable

The king is probably rich.

Adjectives which already end in -te do not add it again:

Falau †ani…te eryßu!

Falauťaniḣte eryśu !

you.POL annoying not-POL

You are not annoying, sir!

A perfective can be formed by appending -u (replacing a final vowel if any) and interchanging it with the previous vowel. Use -y instead if the latter is also a -u-.

Kri…eu ßaudi.

Kriḣeuśaudi .

killer beautiful-PERF

The killer is no longer beautiful. (Cf. śaida 'beautiful')Falte nyne mycu.

Falte nynemycu .

you-SUB girl young-PERF

Your daughter is no longer young. (Cf. muc 'young']

Predicate adjectives are not inflected for volition or effect.

An adjective can be used as a substantive by suffixing -te: syhte 'the strong (ones)', kyrte 'the green (ones).'

The subordinated form may also appear attributively; in this form and position it can be interpreted as a one-word relative clause.

Note the difference between:

nyyl nabira a slow ship

nyylte nabira a ship that is slow

nyylte a slow one

There is no morphological comparative. A comparative 'X is more Q than Y' is formed using an expression that literally means 'As opposed to Y, X is very Q.'

Cadec ceuste polte nyne leule.

Cadec ceuste polte nyne leule.

hill-girl opposing city-SUB girl cute-AUG

A city girl is cuter than a hillbilly girl.Bodu ceuste ßemu bontuurte eßu.

Bodu ceuste śemu bontuurte eśu.

frog opposing fish wet-AUG-SUB not

A fish is not wetter than a frog.

Instead of bontuurte eśu 'not very wet' we could say bontuir 'little wet'; but the negative expression is preferred in speech, where the difference from bontuur 'very wet' is not marked.

Note that where we use comparative forms Kebreni often uses the augmentative or diminutive forms: nyul lore 'slower horses', literally 'very slow horses'. Reduplication is also found, especially in speech: kasus kasus re 'a windy, windy day'.

Before a verb, the -te form of an adjective serves as an adverb:

Nyne

nyylte taradu. The girl was dancing slowly.

Linnahazikte nuzi. The lord spoke proudly.

This form can follow the verb if it would not be confused with an object: nuzi hazikte is all right, but taradu nyylte would mean 'danced a slow one'. It can be fronted for emphasis, but only by placing it in its own subclause with tasu/soru 'do':

Úazikte tauste linna nuzi.

Hazikte tauste linna nuzi.

proud-SUB doing lord speak-PERF

Proudly the lord spoke. (Lit., Doing proudly, the lord spoke.)

Applied to two (or more) modifiers, -ai forms an intersection, eḣc a union, of the meaning of the modifiers. For instance, muk syh neḣatai and muk syh eḣc neḣat both mean 'the young and strong men'; but muk syh neḣatat means the men who are both young and strong (the intersection of 'young men' and 'strong men'), while muk syh eḣc neḣat means the young men and the strong men (the union of 'young men' with 'strong men').

The third logical possibility is a disjunction— the men that are young or strong but not both— and this corresponds to ga 'or': muk ga syh neḣat 'the old or the young men (but not both)'.

Similarly, applied to separate words, -ai implies that both conjoints describe the same referent(s) or action, eḣc that they are separate, and ga that only one applies:

(Here the referents are not the same. When the conjoints are obviously distinct, the meaning is that they form an indissoluble team, acting together.)Úem falaai inezu.

Ḣem falaai inezu.

you I-AND speak-VOL

You and I (as a unit or team) will speak.

Úem e…c falau inezu.

Ḣem eḣc falau inezu.

I and you.POL speak-VOL

You will speak, and I will speak.Úem ga falau inezu.

Ḣem ga falau inezu.

I or you.POL speak-VOL

Either you will speak, or I will speak.nyne taradeai

the girl and the dancer (who are the same), the girl dancer

nyne eḣc taradeu

the girl and the dancer (who are two separate people)

nyne ga taradeu

the girl or the dancer (but not both)Palec symalu ťaniḣuai.

Palec bores and she annoys (all at once, simultaneously).

Palec symalu eḣc ťaniḣu.

Palec bores and she also annoys (two different attributes).

Palec symalu ga ťaniḣu.

Either Palec bores, or she annoys (not at the same time).

Ga is thus an exclusive or. There is no conjunction that has the meaning of inclusive or (X or Y or both, X and/or Y), but, as in English, one can add the 'and' case explicitly:

Mela… pabadu ga fanu ga kur soru.

Melaḣ pabadu ga fanuga kur soru .

king laugh or die or two do

The king will laugh or die or both (lit. 'or do the two (of them)').

There is no conjunction 'but'— which, linguistically, is an 'and' with a built-in implication of surprise or contrast. These connotations must be explicitly indicated in Kebreni.

Mygu zinu keda!

Myguzinu keda!

ox be.inside house

The ox is inside the house!Raazam neryvu ha…c.

Raazamneryvu haḣc.

Raizumi be.middle-POL valley

Raizumi is in the middle of the valley (polite).

Most of them in fact are regular verbs— e.g. foru 'follow', used as a locative verb with the meaning 'be behind', mitu 'use' or 'be with'. The others were also once regular verbs, but are no longer used in their original meanings.

More frequently a locative expression is used as a modifier or an adverbial; these are subordinate clauses in Kebreni. The locative verb conventionally ends the expression, although its parameter is technically a direct object (more evidence, perhaps, for Meťaiun's OV nature):

ingarei ziunte inside the tavern

re neuvte in the middle of the day[ḣir zeveu eupte] lyr muhnu

sad news [from an old friend][lim men fourte] keda

the high hill [in back of the house][melaḣ miutte] linna

the lords who support the king[[kaldu ziunte] gem bakte kal ] ḣulo

an idiot [without one fucking bee [in his hive]]

These expressions are so frequent that they are phonetically degraded. The -u- is often lost, or combines with a preceding -i- or -e- to form -y-, and the final -e may be lost as well, yielding such forms as zynt' 'inside' or fort' 'in back of'.

English has at least one verb that acts like a locative verb— 'contain'. Kebreni locative verbs all act like 'contain'. Compare:

Kona zinu ci…ta ci…ta ziunte Kona zinu ciḣtaciḣta ziunte The money is in the box in the box Ci…ta zadinu kona kona zadiunte Ciḣta zadinu konakona zadiunte The box contains money containing money

The most common locative verbs, and the abbreviations used in derivations from them, are shown below, with some examples:

Time metaphorically flows not forward but downward in Kebreni:

brynu bry facing, before, about keda bryunte 'in front of the house', kriidi bryunte about books' dynu dy up, on top of, over cadu dyunte 'over the mountains' ebu eb out (of), off, (away) from Kebri eupte 'outside Kebri' cezu cez against, despite źaiźega ceuste 'against the marriage' foru for behind, in back of keda fourte 'behind the house' fuzu fu without śemu fuuste 'without a fish' mitu mi with, using; supporting abaźe miutte 'with a knife' nevu ne in the middle of, among, through, during nabira neufte 'in the middle of the ship', mur neufte 'for an hour' ponu po below, under broga pounte 'under the table' śadamu śada far (from) pol śadaunte 'far from the city' śamu śa around, surrounding, near turgul śaunte 'surrounding the battalion' vekru vek as, like gauryr vekurte 'like a virgin' zinu zi in, inside, at, on(general locative) laḣ ziunte 'in the field', men ziunte 'on top of the hill', ťiron ziunte 'at market' zadinu zadi containing, including seť zadiunte 'containing a jewel'

mur dyunte an hour ago (lit., up an hour)

mur pounte an hour later, after one hour (lit., down an hour)

One can flow with a river or against it; expressions of support work the same way.

Tama miutte with (down) the Serea

Tama ceuste against (up) the Serea

melaḣ miutte/ceuste for/against the king

Finally, note that interrogative 'where' is a locative verb:

Syna ßanu?

Syna śanu?

waterfall where

Where is the waterfall?

Yes-no questions are indicated with intonation alone:

Lahu?

Lahu?

Are you coming?Úulo, mi#unte …itane eßu?

Ḣulo, miźyunte ḣiťane eśu?

idiot / bringing sword not

Idiot, you didn't bring your sword?

A positive question is answered by repeating the verb or by contradicting it with the negative auxiliary eśu; there are no words for 'yes' or 'no'.

Lahu. Yes, I'm coming.

Eśu. No, I'm not coming.

To agree with a negative question, you again repeat the verb, which of course is the negative auxiliary eśu; to disagree with it you use the main verb:

Eśu. Yes, I didn't bring it.

Miźynu. No, I did bring it.

Tag questions are formed with eśu (polite natu), without subordinating the main verb:

Laadum ßemuste lecu, eßu?

Laadum śemuste lecu, eśu?

Laadau-MAN swimming know.how / not

Someone from Laadau knows how to swim, doesn't he?Mela… karynu …em, natu?

Melaḣ karynu ḣem, natu?

king see-POL I / not.POL

The King will see me, won't he?

It should come as no surprise that a negative tag-question is formed by appending the non-negative main verb:

Fal fuuste kona eßu, fuzu?

Fal fuuste kona eśu, fuzu?

you lacking money not / lack

You don't have any money, do you?

Unlike in English, question words are not fronted; they remain in the syntactically appropriate spot:

Fal cyru ßava?

Fal cyruśava ?

you know who

Who do you know? (Lit., you know who?)Ma…u ßava loreai?

Maḣuśava loreai?

sell-PERF what horse-and

You sold the horse and what else? (Lit., you sold what and the horse?)Oteurte lore zeveu ßanu?

Oteurte lore zeveuśanu ?

VOL-acquire-SUB horse friend where

Where's this friend of yours who wants a horse?Kuna ßete ßemu?

Kunaśete śemu?

see-PERF what kind fish

What kind of a fish did you see? (Lit., you saw what-kind-of fish?)Kylsu bigynte ladu?

Kylsubigynte ladu?

order-PERF how many olive

How many olives did you order?

Verbs such as say or know can take sentences as objects. If the object is in its usual place, after the verb, no special syntactic marking is employed:

Cyru Verdureu ame…u baba.

Cyru [Verdureu ameḣu baba].

know [Verdurian VOL-sell mother]

We know [that Verdurians would sell their mothers.]Kulseu nizeu turgul zinu kuri ßogu.

Kulseu nizu [turgul zinu kuri śogu].

commander say [battalion be.at that ridge]

The commander says [the battalion is on that ridge.]

If it's desired to front the sentential object, it should be followed by gente 'this one' or kurite 'that one':

Verdereu ameæu baba gente cyru?

[Verdureu ameḣu baba] gente cyru?

[Verdurian sell-VOL mother] this-one know?

That Verdurians would sell their mothers, do we know this?

The conjunctions eḣc and ga can be used for entire sentences:

Mela… zinu ingarei e…c ingareu zinu …yr.

Melaḣ zinu ingareieḣc ingareu zinu ḣyr.

king be.in tavern and tavernkeeper be.in castle

The king is in the tavern,and the tavernkeeper is in the castle.Úilu inga ga ingarei ziunte ßaida nyne diru.

Ḣilu ingaga ingarei ziunte śaida nyne diru.

like wine or tavern being.in beautiful girl work

Either he likes the wine, or a beautiful girl works in the tavern.

Other relations between sentences are expressed by more specialized conjunctions. These are often expressed by adverbial clauses in English. Thus English adverb X (adverb) Y becomes X (conj) Y in Kebreni:

Mela… kaaryru perma falau y…ervu …ifane.

Melaḣ kaaryrupema falau yḣeryvu ḣiťane.

king return-PERF-POL when you VOL-give swordWhen the king returns, you will give him your sword.Mela… kaurte natu he# falau oteryru …iitiru.

Melaḣ kaurte natuheź falau oteryru ḣiitiru.

king returning not-POL if.then you VOL-take-POL sashIf the king does not return, (then) you will take his sash.Úem …ou#i kriida immi konarei mengu.

Ḣem ḣouźi kriidaimmi konarei mengu.

I lose-PERF mortgage-SUB paper because.of.that bank whineBecause I lost the mortgage document, the bank is whining.

The conjunction is considered to modify the first (X) clause. To second clause can however be fronted if a demonstrative is left in its place:

Konarei mengu, …em …ou#i gemeßate kriida immi kurite.

Konarei mengu, ḣem ḣouźi gemeśate kriidaimmi kurite .

bank whine / I lose-PERF mortgage-SUB paper / because that.one

The bank is whining, because I lost the mortgage document.

'To do X in order to Y' is expressed by placing X in the volitional and subordinating Y:

Alamute aeladu.

Alamaute aeladu.

get-money-SUB spend-money-VOL

In order to get money, you must spend money.¸yunte Kebropol …em oteru lore.

Źyunte Kebropol ḣem oteru lore.

go-SUB Kebropol I acquire-VOL horse

I want to get a horse in order to get to Kebropol.

As noted under Pronouns, interrogative pronouns cannot be used as relative clauses (that is, to form subordinate clauses).

Where English would use 'what', 'who' 'where', or 'when', Kebreni uses the subordinating form of the verb:

¸ai#iute kulseu taradeu …iulte eßu.

[Źaiźiute kulseu] taradeu ḣiulte eśu.

[marry-PERF commander] dancer liking not

The dancer [who married a commander] doesn't like him.Cuka miute gente eveßu.

[Cuka miute] gente eveśu.

[pimple having] that.one VOL-not

I don't want the one [who has a pimple].Y#enu hamaida nyne tarautte ingarei

Yźenu [hamaida nyne tarautte] ingarei.

VOL-go [stripped girl dancing] tavern

I want to go to the tavern where the naked girls dance.

An English sentence with relative 'why' will be expressed using immi 'because' in Kebreni:

¸yunte Laadau immi cyurte eßu.

[Źyunte Laadau immi] cyurte eśu.

[going Laadau because] knowing not

I don't know [why he's going to Laadau].

(Lit., I don't know because he's going to Laadau.)

For a brief intro to transformations, see the Verdurian grammar. For a longer one, see the Xurnese grammar. And for a whole book, see my Syntax Construction Kit.

To mark focus, a constituent is moved to the front of the sentence. With compound sentences, the constituent in focus may serve as either subject or object in the sentence; context usually serves to keep the meaning clear, without any unusual syntax or the insertion of pronouns.

Muk bo†eneum, sudy Kamum, e…c kulseu …ilu.

Muk boťeneu sudy Kamum, eḣc kulseu ḣilu.

young soldier / name Kalum / abd commander like

The young soldier, [he] is named Kamum, and the commander likes [him].Linnate nyne gegeu mi#ynu gembadu.

Linnate nyne gegeu miźynu gembadu.

lord-SUB daughter servant bring breakfast

As for the lord's daughter, the servants are bringing breakfast [to her].

Note that when there are two noun phrases before the verb and no object after it, the first must be the object. If there's just one noun phrase before the

Hus nynete baba agenu #e.

Hus nynete babaagenu źe.

doctor girl-SUB mother VOL-see also

As for the doctor, the girl's mother wants to see him too..Nynete baba agenu hus #e.

Nynete babaagenu hus źe.

gilr-SUB mother VOL-see doctor also

As for the girl's mother, she wants to see the doctor too.Ne…at guma mabu.

Neḣatguma mabu.

man bite-PERF dog

Man bites dog. (focus unmarked or on 'man')Mabu guma ne…at.

Mabuguma neḣat.

bite-PERF dog man

Dog bites man. (focus unmarked or on 'dog')Ne…at mabu guma.

Neḣat mabuguma .

man bite-PERF dog

As for the man, the dog bit him. (focus on 'man')Mabu ne…at guma.

Mabu neḣatguma .

bite-PERF man dog

As for the dog, the man bit him. (focus on 'dog')

Schematically:

NP V = S V

V NP = V O

NP V NP = S V O

NP NP V = O S V

The relative clause can be headless; or to put it another way, the subordinated phrase can be used as an argument NP:Nyne a#ei#igu.

Nyne aźeiźigu.

girl VOL-marry

The girl wants to get married.> a#ei#iucte (nyne)

aźeiźiucte (nyne).

VOL-marry-SUB (girl)

(the girl) who wants to get married

The use of the -te form with auxiliaries can be seen as extension of this: the entire subordinated sentence is the subject of the auxiliary. Compare:Kalum gennyr nizu a#ei#iucte.

Kalum gennyr nizuaźeiźiucte .

Kalum only speak VOL-marry-SUB

Kalum only talks to those who want to get married.

The subordinated sentence modifies a noun. But it can also modify an entire sentence, in which case it’s placed before the verb (exactly like -te adverbs):

Boß maru.

Boś maru.

failure be.likely

Failure is likely.Kalum boßte maru.

Kalum bośte maru.

Kalum failure-SUB be.likely

It’s likely that Kalum will fail.

In this usage, if there is an object (not merely an additional modifier), the construction is usually fronted or backed.a#ei#iucte toryveu Nyne Kebropol #uny.

Nyne Kebropolaźeiźiucte źuny.

girl Kebropol VOL-marry-SUB go-PERF

Wanting to get married, the girl moved to Kebropol

The subordinated sentence can be the object of a preposition (locative verb). This is one occasion where two -te forms may adjoin.¸i#uicte toryveu, nyne Kebropol #uny.

Źiźiucte toryveu , nyne Kebropol uźuny.

marry-SUB trader / girl Kebropol go-PERF-VOL

The girl moved to Kebropol in order to marry the trader.

This includes vekru ‘like, as’, which is a locative verb in Kebreni:Gymu ibreni pombaadarei bihate faunte fuuste.

Gymu ibreni pombaadareibihate faunte fuuste .

we explore-BENEF-VOL sub-cellar anyone dying lacking

We’re going to explore this dungeon without dying.

This can of course be shortend to Mykneu vekurte ‘like Mykneu’.Cin kriutte leriucte eßu Mykneu kriutte vekurte.

Cin kriutte leriucte eśuMykneu kriutte vekurte .

I-PEJ write-SUB can-SUB not Mykneu-SUB write-SUB as-SUB

I can’t write like Mykneu writes.

As shown above, a subordinated sentence may be followed by immi to express purpose. Cf. aźeiźiugte immi ‘because she wanted to marry’.

The former object, if given, is properly marked with bryunte. However, if no confusion is likely and the subject is not given, this can be left out: Kebropol źynau ’departure for Kebropol’; kahaba ḣemi ’the drinking of coffee’. But: Maźigate kahaba bryunte ḣemi ’Maźiga’s drinking of coffee’Ma#iga dyvuti Verdereu.

Maźiga dyvuti Verdereu.

Maźiga beat-PERF Verdurian

Maźiga beat the Verdurians.> Ma#igate (Verdureu bryunte) dyveti

Maźigate (Verdureu bryunte) dyveti

Maźiga-SUB (Verdurian facing) victory

Maźiga’s victory (i.e. beating) over the Verdurians> Verdureu bryunte dyveti

Verdureu bryunte dyveti

Verdurian facing victory

victory over the Verdurians

This works with person nominalizations too: Verdureute dyviteu ‘the victor over the Verdurians’. As only the object can be referred to, bryunte is omitted.

The other is to promote the causee to direct object of the main clause, and use the subordinating form for the subclause:Lelec somura (mabu buda akennu).

Lelec somura [mabu buda akennu].

Lelec cause-PERF [dog eat-PERF evidence]

Lelec made the dog eat the evidence.

Though the meaning basically is the same, this is more direct— here, it confirms that the causation was intentional and not accidental.Lelec somura (akennu baudte) mabu.

Lelec somura [akennu baudte] mabu.

Lelec cause-PERF [evidence eating] dog.

Lelec made the dog eat the evidence.

In this sense foru can be conjugated normally. E.g. here volitional ...ofure would mean ‘...and the cat wanted to.’Mabu buda sus, e…c neku buda sus.

Mabu buda sus, eḣc neku buda sus.

Mabu eat-PERF mouse / and cat eat-PERF mouse

The dog ate a mouse, and the cat ate a mouse.> Mabu buda sus, e…c neku furo.

Mabu buda sus, eḣc nekufuro .

Mabu eat-PERF mouse / and cat follow-PERF

The dog ate a mouse, and the cat did too.

The verb may be supplied as a conversational response.

—Cin ikrude kuri kriidi.

—Cin ikrude kuri kriidi.

I-PEJ write-PERF-VOL that book

”I wanted to write that book.”—Furo?

—Furo?

thus-PERF

”And did you?”

Note that this is an instance of foru as conjunction ‘thus’, not as a VP anaphor!Verdureu toru Yndana, foru gymu toru Angenvari.

Verdureutoru Yndana, foru gymutoru Angenvari.

Verdurian take Téllinor / therefore we take Angenvari

The Verdurians are taking Téllinor, so we are taking Angenvari.> Verdureu toru Yndana, foru gymu Angenvari.

Verdureutoru Yndana, foru gymu Angenvari.

Verdurian take Téllinor / therefore we take Angenvari

The Verdurians are taking Téllinor, so we are taking Angenvari.

Very similarly, if two conjuncts share an object, it can be omitted in the second sentence. (Not the first, as would be more likely in English.)

Verdureu hantoru Nam immi gymu ce…nu Nam.

Verdureu hantoruNam immi gymu ceḣnuNam .

Verdurian invade Nan because.of.that we defend Nan

Because the Verdurians are invading Nan, we are defending Nan.> Verdureu hantoru Nam immi gymu ce…nu.

Verdureu hantoruNam immi gymu ceḣnu.

Verdurian invade Nan because.of.that we defend

The Verdurians are invading, so we are defending, Nan.

Naturally you’d have Kalum zaurte eśu... for ‘It’s not Kalum who wants to drink wine.’ Colloquially this can be simplied to Kalum eśu...Kalum u…emu ingu.

Kalum uḣemu ingu.

Kalum drink-VOL wine

Kalum wants to drink wine.> Ingu zaru, Kalum u…emu.

Ingu zaru, Kalum uḣemu.

wine exist / Kalum drink-VOL

It’s wine that Kalum wants to drink.> Kalum zaru, u…emu ingu.

Kalum zaru, uḣemu ingu.

Kalum exist / drink-VOL wine

It’s Kalum that wants to drink wine.

The verb can then be replaced with tasu/soru ’do’. In this case, any adverb modifying the original verb moves to the dummy object.Lelec nyylte taruda.

Lelec nyylte taruda.

Lelec slow-SUB dance-PERF

Lelec slowly danced.> Lelec nyylte taruda taradi.

Lelec nyylte tarudataradi .

Lelec slow-SUB dance-PERF dance

Lelec slowly danced a dance.

> Lelec tusa nyyl taruda.

Lelectusa nyyl taradi.

Lelec do-PERF slow dance

Lelec did a slow dance.

hamare scúreden country cymure širden moon sovundre fidren night ozurre calten sun boḣture zëden sea ťiron néronden market seḣepre ceďnare eating (i.e. feast)

The leap day is called forźycisa, a calque on Ver. kasten ‘hidden day’.

muccymu olašu new month śonsi reli sowing seḣapna cuéndimar celebration aḣimba vlerëi goddess Vlerë geḣgu calo heat ede recoltë harvest forźynau yag hunt ḣela želea calm zavec išire planet Išire sylgo šoru shadow rikas froďac cold wind varu bešana ending

The Kebreni kaamza is slightly larger than the Verdurian cemisa: 758.19 m rather than 758 m. The prozma is cognate to the Verdurian proma, but the Kebreni found it more useful to make it 4 times larger.

Unit Relation In hui Metric Etymology śenu 1/12 huiḣ 0.02083 1.98 mm smallness huiḣ 1/4 hui 0.25 2.38 cm dim. of hui hui base 1 9.525 cm finger zeta 5 hui 5 47.625 cm arm neḣagu 3 zeta 15 1.429 m body lore 2 neḣagu 30 2.858 m horse prozma 1/125 kaamza 63.68 6.065 m (Caď.) pace kaamza 125 prozma 7,960 758.19 m (Caď.) size of Caema temple

Area is measured in prozmana, which are 100 square prozma, i.e. 3678.2 m² or 0.37 hectare.

In 3615 Kebri adopted a decimal measurement system. It adopted the international Xurnese System instead in 3636, but the older system persisted in many domains.

The basis of the system was the hui, unchanged at 9.525 cm. Rather than using prefixes, new names were created for the derived units:

Informally, hui is sometimes used for mein, the 7.6 cm unit that is the basis for the Xurnese system.

Unit Multiplier Metric śeiḣ 1/100 0.9525 mm śeina 1/10 9.525 mm hui 1.0 9.525 cm linniḣ 10 95.25 cm linnu 100 9.525 m leḣos 10000 0.9525 km

Personal names may be just about any appropriate noun or adjective (Syna ‘waterfall’, Miry ‘rich’, Caiźiru ‘type of flower’), but are often formed with nominalizations: e.g. kal ‘oak’ > masculine Kalum, feminine Kalec; Ḣileu ‘devotee’.

Family names often indicate a geographic origin, specific (Kotor, Nynoḣu, Nevurte) or vague (Lezum ‘of the forest’, Vaarum ‘of the coast’, Ebaneu ‘foreigner’). Profession names are common: Kopureu ‘distiller’, Lazum ‘farmer’, Seťarei ‘silk workshop’. Yet others derive from nicknames or other qualities: Pansyr ‘loveable’, Voiteu ‘blind’, Cymure ‘(born on) širden’.

A full title comes between the names: Zauvum linna Tivatemeu ‘Zaauvum, lord Tivatemeu’; Sygec dibira Oriśaga “prime minister Sygec Oriśaga’, Śogum ziedu Numygur, ‘lieutenant Śogum Numygur’. On second reference you omit the personal name. Unlike in Verduria, nobles do not have separate family and title names.

Eleďî normally but not always take Elenico names— rarely Cuzeian ones. These have been adapted from Old Verdurian (rather than directly from Greek, or from Verdurian):

Masculine Agusto Filemo Klemen Nikano Timoťeu Akulaḣ Filipo Koḣmo Nikolo Tito Alekso Gaho Korneu Oano Tomeu Ämilo Gamaleu Kuro Osef Tuḣiko Antono Gavrel Lavreno Pavlo Tuḣon Apelen Gregoro Lazaro Petro Ťadeu Apolo Gyrgo Lino Rufo Ťamano Äron Helaḣ Lukano Sameu Ťanel Atipaḣ Heso Lukaḣ Savlo Ťaro Aťam Ḣisforo Marko Sergo Ťavid Aťano Ida Maro Sevaḣtan Ťemetro Aťra Ikovo Martino Silaḣ Ťonuso Avräm Ilo Mato Simon Ťydoro Egeno Ison Maťeu Solomon Varnavaḣ Emaneu Isäc Meliťec Sosťen Vaťolomeu Eraḣto Isu Miḣäl Stefano Vasileu Ezekaḣ Kefaḣ Moso Sumon Venamen Felics Kläťo Naťaneu Timeu Zaḣaraḣ Feminine Agaťe Evgeni Luka Reveka Ťedora Äkatrine Fernike Luťi Roťe Ťerasi Aleťe Foive Luťuka Ruťa Ťorka Aleksa Hagne Margite Sarra Varvara Ämila Helena Mari Sofi Vaťolomec Anna Ḣarma Martina Suntiḣ Vasilec Angela Ḣloe Melani Susana Verena Antona Ila Miḣäla Tadec Vernike Aťana Iriḣ Natali Taviťa Vetriksa Aťera Käkila Oana Timoťec Zaḣara Elisveta Kläťa Persiḣ Trufäna Esťera Koḣma Petra Ťamariḣ Eva Ksena Priska Ťanela Evnike Loiḣ Raḣeli Ťara

A pitfall for Verdurians: ß # ś ź are the same letterforms as Verdurian š ž but appear in a different place in the alphabet. Programmers solved this problem for themselves, but created one for the users, by giving these characters different code points.

u u u † ť ťen a a a z z zaḣ o o o t t ten e e e ß ś śe i i i # ź źe y y y r r ra k k ek h h hoť p p pe l l la c c ceḣ m m me b b be f f faḣ g g geḣ n n ne d d dah v v vaḣ s s saḣ … ḣ ḣik

In the interlinear translation, for brevity, I've used the English possessive or gerundive to represent subordinating forms of nouns and verbs, respectively. However, I've used verbal forms to translate locative verbs; prepositions would misrepresent the structure of Kebreni.

Writing addressed to the world in general (stories, essays, textbooks, news articles) generally does not use the polite forms. When the writer has a specific audience in mind (speeches, petitions, personal letters, sermons), polite forms are used. They are not used in religious language or in legal documents--not signs of disrespect for gods or negotiation partners, but of the age of such language, predating the grammaticalization of politeness.

Uneitsu Kebri. Nuutsi ßava?

Uneitsu Kebri. Nuutsi śava?

think-VOL Kebri. think-PERF what?

Think of Kebri. What do you think of?

Ha…c ziunte sylgu, luda kuguynte men, boætunate geira †aupte yvyre.

Haḣc ziunte sylgu, luda kuguynte men, boḣtunate geira ťaupte yvyre.

valley being-in shadow, olive-tree filling hill, sea's sound lapping boats.

You think of the shadows on the valleys, the hills carpeted by olive trees, the sound of the sea lapping against boats.

Nuitu ziunte kanu hazik pol, nabirateu e…c konarei e…c ingarei miutte,

Nuitu ziunte kanu hazik pol, nabirateu eḣc konarei eḣc ingarei miutte,

mind being-in see proud city, shipbuilder and bank and tavern using

You see in your mind the proud cities, with their shipbuilders and banks and taverns,

geru kebrite ceirate lyyr zauguai, ansu ßaida kebren nynete …ir mova,

geru kebrite ceirate lyyr zauguai, ansu śaida kebren nynete ḣir mova,

hear kebri's song's sadness glory-and, feel beautiful kebreni girl's long hair

hear the sadness and glory of Kebreni songs, feel the long hair of beautiful Kebreni girls,

debru falte ha…c ga falte no…a ziunte tauste i#ele, Kebri ziunte dynyr.

debru falte haḣc ga falte noḣa ziunte tauste iźele, Kebri ziunte dynyr.

taste your valley or your island being-in making cheese, kebri being-in top

taste the particular cheese made in your own valley or island— the best on Kebri.

Fal kebren immi nuitsu orat kurite.

Fal kebren immi nuitsu orat kurite.

you kebreni because think all that-NOM

You think all this because you are Kebreni.

Verdureu nuitsu, kebri zikanu gente: ingu, ladute gezu, nabira zateuguai.

Verdureu nuitsu, kebri zikanu gente: ingu, ladute gezu, nabira zateuguai.

verdurian think, kebri mean this-NOM: wine, olive's oil, ship, enmity-and

To the Verdurians, Kebri means these things: wine, olive oil, ships— and enmity.

Gymu …i…unte Ru…tyrte rema hami, toryuvte ˇe˙nam hami, Moreo Aßcaite mela… bryunte ledeu.

Gymu ḣiḣunte Ruḣtyrte rema hami, toryuvte Ťeḣnam hami, moreo aścaite melaḣ bryunte ledeu.

we burning arcaln's bridge land, trading dhekhnam land, moreo ašcai's king facing rival.

We are the land which burned the Arcaln Bridge, the land that trades with Dhekhnam, the rival before the king of Moreo Ašcai.

Oratte ceuste, nana miutte, tasu oradam ziunte dynyr ingu,

Oratte ceuste, nana miutte, tasu oradam ziunte dynyr ingu,

all-NOM opposing, methods using, make world being-in top wine,

And at the same time, somehow, we make the finest wine in the world,

Kelenor Luißorai ceuste …auv miuryai.

Kelenor Luiśorai ceuste ḣauv miuryai.

celenor luyšor-and opposing good-AUG rich-AUG-and

better and richer than that that of Célenor or Luyšor.

Gensi e…c gennisi. Kanu gymu oradam vekurte:

Gensi eḣc gennisi. Kanu gymu oradam vekurte:

same-for-me and same-to-you. see us world seeming:

It is the same way with each one of us. We see ourselves as a world—

bucuelecsu cynaute kumbehsu meclau.

bucuelecsu cynaute kumbehsu meclau.

irreducible experience's miscellaneous mixture

a jumbled mixture of irreducible experience.

Ebaneu kanu bemaß miutte— gente ceuste, gymu kaunte eußte #aite †aza kanu.

Ebaneu kanu bemaś miutte— gente ceuste, gymu kaunte euśte źaite ťaza kanu.

outsider see caricature with— this-NOM opposing, we seeing not-SUB things they see

Outsiders see us in caricature— but may also see what we do not see:

Bobabeu nuituste eßu …ymu kunnar.

Bobabeu nuituste eśu ḣymu kunnar.

drunkard thinking not-PRES drinks too-much

the drunkard never thinks he drinks too much.

Kanarei geme… do…tte eśu, kure… do…tte eßu:

Kanarei gemeḣ doḣtte eśu, kureḣ doḣtte eśu:

viewpoint first right-SUB not, second right-SUB not-PRES

Neither point of view is the correct one

ne…atte #aite miutte, nenkanyr kanarei zaurte eßu.

neḣatte źaite miutte, nenkanyr kanarei zaurte eśu.

man's thing having, objective viewpoint existing not

with human things, there is no objective viewpoint.

You can learn some common expressions from this dialog, as well as how to use the polite and pejorative forms.

KALUM (tastauste). Din Linna. Linna Broida. Falaute reikau vatar tra#agu.

KALUM (tastauste). Din Linna. Linna Broida. Falaute reikau vatar traźagu.

Kalum / trying / hon. lord / lord Broida / you.POL-SUB meeting endless pleasure

KALUM (practising). Sir Lord. Lord Broida. What a pleasure it is to meet you.

Kaunte lerycu falaute zizavaute baadarei?

Kaunte lerycu falaute zizavaute baadarei?

seeing can-POL you.POL-SUB famous cellar

Could I see your famous wine cellar?

Luriha falaute nyne fourte. Falaute nynete amma fourte.

Luriha falaute nyne fourte. Falaute nynete amma fourte.

come-POL-PERF you.POL-SUB daughter following / you.POL-SUB daugher-SUB hand following

I've come for your daughter. For your daughter's hand.

Ehemarybu kurite, fynpila.

Ehemarybu kurite, fynpila.

VOL-POL-give.up that.one naturally

If you wish to give it up, of course.

Falau cyurte, cin reuriki falaute nyne. Ga †a… cyru? Eßu he# …avna.

Falau cyurte, cin reuriki falaute nyne. Ga ťaḣ cyru? Eśu heź ḣavna.

you.POL knowing / I.PEJ meet-PERF-POL you.POL-SUB daughter. or 3s know? not if.then good-AUG

As you know, I've met your daughter. Or does he know? Perhaps it’s better if he doesn’t.

Cin reuriki nynete baba. Eßu, cinte baba reuriki falaute #ai#eiga ßaida nyne miutte.

Cin reuriki nynete baba. Eśu, cinte baba reuriki falaute źaiźeiga śaida nyne miutte.

I.PEJ meet-PERF-POL girl-SUB mother / no / I-gen mother meet-PERF-POL you.POL-SUB spouse beautiful daughter with

I’ve met the girl’s mother. No, my mother met your wife, your wife and your beautiful daughter.

Batrounte bißu, amma miutte tauste bißu.

Batrounte biśu, amma miutte tauste biśu.

relaxing must / hand with doing need

I must relax, have something to do with my hands.

(Tourte kriidi) Zizavaute mela…te sabareite lic. Kurite bißu.

(Tourte kriidi) Zizavaute melaḣte sabareite lic. Kurite biśu.

taking book / famous king-SUB court-SUB lawsuit / that.one need

(Taking a book) Famous royal court cases. Just the thing.

Linna kru…ite nynete neßameu lic. Dynyr, dynyrna.

Linna kruḣite nynete neśameu lic. Dynyr, dynyrna.

lord kill-PERF-SUB daughter-SUB suitor lawsuit / excellent excellent-AUG

The case of a lord who murdered his daughter’s suitor. Excellent, excellent.

BROIDA (zi#yynte). Úamenivi.

broida / entering / bless-YOU-BENEF

BROIDA (entering). Greetings.

KALUM (piisa). Orat kem! Úamenirivi, Broga linna,, Bryga linna,, Broida linna.

KALUM (piisa). Orat kem! Ḣamenirivi, Broga linna— Bryga linna— Broida linna.

Kalum / surprised / all god / bless-YOU-BENEF-POL / table lord / trousers lord / Broida[storm] lord

KALUM (surprised). Omigosh! Greetings, Lord Table. Lord Trousers? Lord Broida.

Falaute oste reikau vatar tonzurgu.

Falaute oste reikau vatar tonzurgu.

you.POL-SUB later-SUB meeting endless softness

What a softness it is to meet you at last.

Gente …av kriidi natu? Cin kaunte lericu.

Gente ḣav kriidi natu? Cin kaunte lericu.

this.one good book not.POL / I.PEJ reading can-POL