|

| ||||||

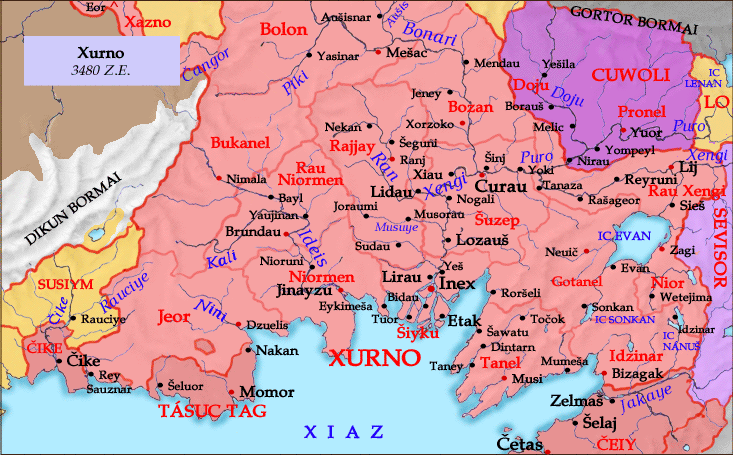

Xurnese, called by its speakers Corauši or Xornaurši, is the language of Xurno, the great Southern nation, and the southern anchor of the multilobed cultural unit which is Ereláe. It is spoken as a primary language by over sixty million people, and as an acquired language by many millions more, to say nothing of the influence it has had on other languages in the Axunaic cultural area (known as Xengiman, the Greater Xengi).

Xurnese, called by its speakers Corauši or Xornaurši, is the language of Xurno, the great Southern nation, and the southern anchor of the multilobed cultural unit which is Ereláe. It is spoken as a primary language by over sixty million people, and as an acquired language by many millions more, to say nothing of the influence it has had on other languages in the Axunaic cultural area (known as Xengiman, the Greater Xengi).

Xurnese is highly dialectalized; each province has its own distinct dialect, and those of the outlying regions (Xazno, Bolon, Jeor, Gotanel, Idenar) are virtually separate languages.

Corauši means ‘Curau speech’, referring to the imperial capital, Curau. Curau dialect is the standard for art, education, commerce, and government. As the fate of regional literature is national indifference, there is only a small amount of serious dialectal writing; most of this is concentrated in the largest cities, notably Inex, Lirau, Jinayzu, and Lij.

As a complication, the present capital is not Curau but Inex. The prestige of Curau as the Xurnese homeland and the home of its greatest writers has so far been sufficient to enforce a Coralaur rather than a purely Inegri standard on the nation; but of course a huge number of very influential speakers are native to Inex rather than Curau. As some have put it, the de facto standard is an resident of Inex attempting to speak Corauši.

The strength of the standard often leads both the Xurnese and outsiders to accord their language more unity than it really has. Xurnese nationalists even maintain that Čeiy speaks a form of Xurnese, although most everyone, especially the Čeiyu, considers Ṭeôši to be a separate language.

This document describes only standard Corauši Xurnese. There is a Language Agency (Šundaus) in Curau which defines the written standard. I’ve tried to follow actual usage rather than the Agency’s prescriptions; but its dictionaries and grammars are invaluable.

In fact Xurnese is a member of the Axunaic branch of the Eastern language family to which Verdurian also belongs. Modern linguists can trot out many similar words (e.g. rama/rana ‘frog’, tas/ta ‘we’, mul/mole ‘soft’) to show this, as well as dissimilar-sounding but related pairs (xu ‘bad’ / čelt ‘evil’, rae/lädan ‘go’, šic/hep ‘seven’).

The affinity has been disguised not only by sound changes, but by semantic and lexical divergence. Xurnese has inherited many words from the Wede:i civilization which preceded it in Xengiman (for details see the Axunašin grammar), as well as from the Skourene and Tžuro cultures it has interacted and struggled with.

Though we say Corauši derives from Axunašin, it’s actually more complicated than that. Before the rise of Axunai, Curau (then named Tural) spoke a variety closer to Mounšun, the dialect of Tannaza. During imperial times the speech of the delta supplanted local dialects throughout Šuzep, the middle Xengi, but without erasing some distinctive local vocabulary and language features. Old Xurnese, the language of the early Xurnese empire (fl. 2700) and the direct ancestor of modern Xurnese, derives from this somewhat divergent form of Axunašin.

Modern Inegri dialect was, in turn, strongly influenced by the language of Curau, which was for a time the larger city. So in some ways Inegri is not a purely straightforward descendant of Axunašin either.

The case is similar to that of Italian, which derives not from Rome but Florence.

The transliteration is the same, except for the affricates and fricatives:

labial alveolar palatal velar stops p t k b d g affricates ts tʃ ks dz dʒ fricatives s ʃ v z nasals m n liquids l r semivowels w j

The b/v distinction is not phonemic; this is a single phoneme pronounced [b] initially and [v] between vowels. I write the allophones distinctly as a frank concession to English speakers (and in imitation of Verdurian transliterations).

labial alveolar palatal velar affricates c č x dz j fricatives s š v z

The use of c and k does not follow Verdurian: c represents /ts/ and k is /k/. C is phonemic, though barely; cf. the minimal pair ceš ‘this one’ / teš ‘halves’. D and dz are also phonemic (cf. dus ‘house’ / dzus ‘in back of’) but even less so, since dz cannot occur finally. Using a digraph for dz reflects Xurnese usage; a word like jadzíes ‘sculptor’ may be written jad-zi-es, whereas c is never split up into *ts.

Somewhat confusingly, x and j generally derive from Axunašin x and j, but represent different sounds. J is /dʒ/ as in English, not Axunašin /ʝ/. X is /s/ initially and /ks/ (as in Axunašin) elsewhere.

(So, x and s have merged initially? Perhaps; but in Inegri initial x is pronounced /z/. Residents of Curau and Inex are aware of this difference and use it to imitate each other. Of course, only literate speakers do a good job of this; the writing system distinguishes between s/z/x.)

e is closed [e] except in diphthongs; o is closed [o] unless followed by an r or n. However, both tend to be more open in closed syllables.

front back high i u mid e o low a

Common diphthongs are ay /aj/, ey /ɛj/, oy /oj/, au or aw /aw/, eu /ɛw/.

Examples:

Xurno ['sur no] Curau ['tsu raw] šeguac ‘bury’ [ʃe gu 'ats] xurney ‘Xurnese’ ['sur nɛj] Corauši [tsɔ 'raw ʃi] jadzíes ‘sculptor’ [dʒa 'dzi ɛs] xurnéy [sur 'nɛj] Endajué [ɛn da dʒu 'e] súmex ‘epoch’ ['su mɛks] Meša ['me ʃa] Inex [i 'nɛks] cunde ‘thus’ ['tsun de] Šuzep [ʃu 'zɛp] Čeiy [tʃɛj] midzirc ‘judge’ [mi 'dzirts] Bolon [bo 'lɔn] cauč ‘dance’ [tsawtʃ] rešeji ‘looked’ [re 'ʃe dʒi] Niormen [ni ɔr 'mɛn] Jeor [dʒe 'ɔr] Bezuxau [be zu 'ksaw]

The transliteration used here is essentially that used by Verdurian and Kebreni scholars, with these differences:

It’s a perfectly serviceable transliteration, and if the b/v distinction is bad phonetics, it helps the Verdurians and it will help English speakers too. Aw/au are merged in Corauši but not in Inegri.

The Xurnese script is part logographic, part syllabic. The syllabic portion is extremely archaic; e.g. Inegri is written

<wei-ne'x-ri>, which matches

<wei-ne'x-ri>, which matches

<wei-ne'x> for Inex and Axunašin Weinex, but is hopeless for a transliteration. Fortunately the Xurnese recognize their pedagogic problem and dictionaries often provide ad hoc phonetic glosses for difficult spellings. These match the Verdurian transliterations in almost all cases, and I’ve used them to transliterate words not attested in Verdurian sources.

<wei-ne'x> for Inex and Axunašin Weinex, but is hopeless for a transliteration. Fortunately the Xurnese recognize their pedagogic problem and dictionaries often provide ad hoc phonetic glosses for difficult spellings. These match the Verdurian transliterations in almost all cases, and I’ve used them to transliterate words not attested in Verdurian sources.

Corauši

XurneseIr nevu jadzíes mnošuac.

My niece is dating a sculptor.To am šus bunji dis kes denjic.

He hopes one day to govern a province.Syu cu šus izrues šač.

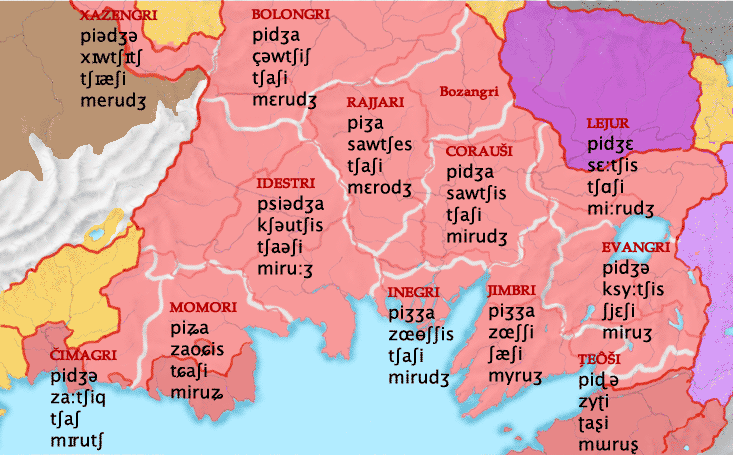

Myself, I don’t envy that province.pija, saučis, čaši, miruj

filth, die, helmets, brain - words from map below

Dialect Region Provinces / States Corauši the middle Xengi, esp. Corau Šiyku Jimbri the Tanel peninsula Tanel, western Gotanel Lejur the upper Xengi Rau Xengi Evangri Lake Van and the southeast Nior, Idzinar, eastern Gotanel Idestri the Ideis valley Niormen, Rau Niormen, Bukanel Rajjari the Ran valley Rajjay, Bozan Momori Jeor Tásuc Tag; eastern Jeor Čimagri the Čiqay valley Čiqay Bolongri Bolon Bolon Xazengri the Hasun valley Xazno

The map shows the pronunciations of four words across Xurno: pija (Ax. pija) ‘filth’ , xaučis (xučik) ‘to die’, čaši (čiaši) ‘enemies’, miruj (meiruj) ‘brain’.

Some characteristics of the dialects, as exemplified by the sample words (but by no means an exhaustive description):

Inegri:

As Tásuc Tag is a separate state, there is a little less pressure to use the standard, but this mostly means that more New Jeori words are used.

In fact these are archaizing fantasies— or at best aids for teaching Axunašin. The grammarians assign ‘case’ according to the Axunašin etymon, inasmuch as Xurnese nouns derive from either the dominant or subordinate case in Axunašin. For instance buma ‘cow’ derives from the subordinate case bouma, while bus ‘bull’ derives from dominant case bouz.

‘Genitives’ are rare, and are best treated as a form of derivational morphology.

‘Gender’ is even easier— e.g. buma and bus are both goro gender, like their etymons. There is no gender agreement in Xurnese, but admittedly the plural paradigms usually correspond to the ancient gender— e.g. nouns ending in -a pluralize in -i (koma ‘house’ → komi) if they derive from the civú gender, but in -ay (rina ‘river’ → rinay) if they were goro gender. But instead of learning an arbitrary gender for many words, why not just remember the arbitrary plural?

The table below summarizes the most common patterns (excluding vowel changes). Quite a few plurals are predictable— especially for those with a good knowledge of Axunašin—but it may be easiest simply to memorize the plural for each noun. The lexicon gives plural forms for all nouns that have one.

Nouns in Plural Examples -a -i

-aykoma → komi

rina → rinay-c -p

-r

-yšuc → šup

gec → ger

juc → juy-irc -ircú nusirc → nusircú -č -š (but some -c) beč → beš -d -c red → rec -e -i nune → nuni -i -w

-útorei → torew

eči → ečú-k -ki reyk → reyki -um -we kasum → kaswe -m -mi dum → dumi -n -ni

-núraun → rauni

meyn → meynú-udo -udzú ammudo → ammudzú -o -u goro → goru -p -pi

-vúcip → cipi

teyp → teyvú-r -ri

-rúber → beri xor → xorú -s -c

-

-si

-m

-súros → roc

ujes → uje

mis → misi

dus → dum

yeys → yeysú-š -č

-šiješ → jič

seš → seši-u -ú saysu → saysú -x -s aušex → aušas -Vy -V’y zalay → zaláy -z -zi

-zúxiaz → xiazi

moz → mozú-C (vowel change) kon → keun

saul xuma a young man

sauli xumi young men

saulú payvú young fathers

sauláy zaláy young warlords

saulé yaté young masters

saulwe edwe young slaves

The adjective does not attempt to match pluralization by consonant or vowel change:

saul emur young husbands

saul nyew young emperors

saul imimes young sea captains

Some adjectives (indicated in the lexicon) have a separate root in the plural: reu mes beautiful woman, reuri mesi beautiful women.

Use the singular form with pronouns or unexpressed subjects (e.g. Saul izom We are young).

Adverbs are formed with the postposition ga: reu ga ‘beautifully’. (Axunašin -oyo survives in a few words as -yo, as in rumyo ‘a long time’, but these are now just lexical anomalies.)

Comparatives are formed with pali, dopali ‘more, less’; superlatives with dzulé, dzudo ‘most, least’: pali saul ‘younger’, dzulé saul ‘youngest’. The term of comparison may be expressed by subordination: yuti na pali reu more beautiful than flowers.

In form the high 2nd and 3rd person pronouns derive from forms meaning e.g. ‘your greatness’ (Ax. rir ezičou), ‘his/her greatness’ (toiš ezičou). These are attested in many forms showing varying levels of abbreviation.

singular plural high low high low 1 siu si tas ta 2 riezič ri miezič moš 3 tošezič to kiezič ke

The usage of the high and low forms was quite complex. The grammarians’ explanation was that ‘high’ forms were used for superiors; ‘low’ forms for inferiors. Examples:

The grammarians’ explanation does not explain why nobles addressed lower nobles with ‘high’ forms, as if they were superiors; and does not provide much guidance for speaking to equals. A better formulation might be that the ‘high’ forms are court forms, used to refer to the noble and the educated in social situations.

The high/low distinction has disappared, a victim of the egalitarian climate of the Revaudo revolution. Note that it was the high and not the low forms that survived— in effect, everyone would now address each other as peers of the educated class, which would have been how the Revaudo intellectuals addressed each other.

singular plural nom acc gen nom acc gen 1 syu i ir tas toy cir 2 yes yes oyes myes myes mir 3 pr toš toš tir, otoš kyes kyes xir 3 ob to to tir, oto

The accusative is retained only in the 1st person.

The genitives derive from Axunašin, with the 1s/2s -r ending generalized, except for the 2s and alternate 3s forms which consist of the adposition o plus the nominative form. (O is now a postposition, so these words are archaic in form.)

It is awkward to have just one 3s pronoun; Corauši has therefore innovated an additional one out of the archaic low form. Thus toš serves as a proximative, to as an obviative.

The 3rd person forms given above are used for animate referents only. For inanimates use ceš ‘this one’ or cuš ‘that one’ instead.

singular plural nom acc gen nom acc gen 1 syu ic ir ta to toyš 2 high yezič jezič jezič o mozič muzič muzič o 2 low ri ej rir moš mu mye 3 high toič toič toič o kezič kezič kezič o 3 low to toy toš ke ke key

singular plural nom acc gen nom acc gen 1 si i ir ta to tei 2 ri ej rir moš mon mei 3 to to tir ke ken kei

Adjective Person Place Time Reason Manner question ji ji • je jinar jideym tun jende which who/what where when why how this ci ceš inar idzum citun cinde this this one here now for this this way that cu cuš cinar cideym cutun cunde that that one there then therefore that way none do duox donar duoyo donde no,

nothingnobody nowhere never no way some bunji bunjisu amnar andeym amende some,

somethingsomeone somewhere sometime somehow many maus maussu mausinar mausiga mausende many many people many places often in many ways every ez ezisu eznar ezdeym ezende every,

everythingeveryone everywhere always wholly

For inanimates (things), use ji / ceš / cuš (from the person column) but then do / bunji / maus / ez (from the adjective column). The anaphora in the ‘some’ row can be translated ‘any’ in negative sentences.

Verbs no longer have second person forms in standard Xurnese. Third person forms are used with the second person pronouns (which, as we have seen, developed from respectful third-person expressions).

The following chart shows the three regular conjugations or verb classes, using the regular verbs kalis ‘please’, reše ‘look at’, and čir ‘cook’. Irregular forms are common, and will be discussed below.

(A few verbs have an infinite in -i; they conjugate with the verbs in -e.)

Sound change rendered the ordinary past tense of Axunašin too close to the present, and it was replaced by the past intensive.

Present Perfect -is -e - -is -e - 1s kal-ú reš-ú čir-ú kal-ijú reš-ejú čir-ijú 3s kal-e reš čir kal-ije reš-ej čir-ij 1p kal-um reš-om čir-um kal-ijum reš-ejom čir-ayjum 3p kal-uc reš-ayc čir-uc kal-ijuc reš-ejayc čir-ayjuc Past Future -is -e - -is -e - 1s kal-ije reš-eju čir-ije kal-ip reš-eyu čir-iye 3s kal-ayš reš-eji čir-iji kal-ayp reš-ey čir-í 1p kal-ayjum reš-ejum čir-ijim kal-yum reš-eum čir-im 3p kal-ijayc reš-ejuc čir-ijeyc kal-yayc reš-euc čir-yeyc

The present intensive became the perfect tense.

There are no 2s or 2p forms in Corauši. (There are in certain dialects, notably Bozangri and Xazengri.)

Some mnemonics:

Mnemonics:

Present Perfect -is -e - -is -e - 1s kal-idú reš-imú čir-imú kal-ugú reš-ogú čir-uswe 3s kal-ide reš-im čir-im kal-uge reš-eux čir-aux 1p kal-idum reš-imom čir-imum kal-ugum reš-ogom čir-usum 3p kal-iduc reš-imayc čir-imuc kal-usuc reš-osayc čir-usuc Past Future -is -e - -is -e - 1s kal-idije reš-imeju čir-imije kal-anye reš-enyu čir-anye 3s kal-idayš reš-imeji čir-imiji kal-an reš-en čir-an 1p kal-idijum reš-imejum čir-imijim kal-anum reš-enum čir-anim 3p kal-idijayc reš-imejuc čir-imijeyc kal-anayc reš-enuc čir-anyeyc

The perfect and future forms are regular: izejú ‘I really am’, izeyu ‘I will be’.

Present Past Subj Pres Subj Past 1s zú zyu šui šuyu 3s ze zi šu šúe 1p izom ezum šuom šuum 3p ayzuc ezyuc šuayc šuyuc

The subjunctive perfect and future use the regular endings and the root šu-: šuogú ‘if I really am’, šuenyu ‘if I will be’.

Conjugation Infinitive 1s present 3s present 1p present 1s perfect 1 (-is) jausis jugú juge jugum jausijú pudzis pudú pude pudum pudzijú rues roú ruwe roum ruejú 2 (-e) jidze jidú jic jidom jidejú mide midú mic midom midejú 3 (-0) baus bugú baus busum bausijú dzaus dzusú dzaus dzusum dzausijú aycaur aycorú aycaur aycorum aycaurijú jec jetú jec jetum jecijú kes kezú kes keyzum kezijú

Present 1s dú 3s dzi 1p dom 3p dzayc

Šizenače ‘not be able to’, saragače ‘must not’, jidače the negative passive, and imišače ‘not begin to’ conjugate like zenače.

šače rugačis zenače rače xamače mojač not be not want not know not go not come may not be Present 1s šač rugač zenač rač xamač mojače 3s šači rugači zenači rači xamači mojači 1p šačum rugačum zenačum račum xamačum mojačim 3p šačuc rugačayc zenačuc račuc xamačuc mojačeyc Past 1s šuč ruč zeynauč rauč xamauč mojuče 3s šuči ruči zeynuči rauči xamuči mojuči 1p šučum ručum zeynučum raučum xamučum mojučim 3p šučuc ručayc zeynučuc raučuc xamučuc mojučeyc

There is no negative perfect, future, or subjunctive.

gisu heavy → gisúnic weight2. Simple actions: -u (pl. -ú):

reu beautiful → réuric beauty

saul young → sáulic youth

pij fear → piju3. A state, process, or activity: -udo (pl. -udzú), or -audo following a syllable containing a front vowel:

orae leave → orau departure

rues desire → rou desire

kuli gather → kuludo harvest4. One instance of a repeated process, or one item from a mass: -uc (unacc.; pl. -aup). This is derivation has a pedantic feel and is mostly used in philosophy and science.

ize be → izaudo existence

revi new → revaudo newness

baus inform → búsuc report5. The result of a process: -eč (unacc.; pl. -eš):

payčis greet → páyčuc greeting

šone head of hair → šónuc one hair

brunde promise → brúndeč a promise

pece sing → pídeč hymn

sune dream → súneč dream

jis weak → jisayc wimp7. One who does the action of a verb: -irc (pl. -ircú):

reš tall → rešayc tall person

saul young → sulayc young person

cauč dance → caučirc dancer8. A follower (like -ist) or inhabitant: -su (pl. -sú), a contraction of xuma ‘man’:

jausik lord it over → jausirc tyrant

kezi govern → kezirc governor

Meša → mešasu follower of Mešaism9. Inhabitants and some occupations: -es (unacc.; pl. -é):

beyludo enlightenment → beylusu enlightened one

Jeor → jeorsu

Zešnam Dhekhnam → zešnasu Dhekhnami

Asuna Axuna → asúnes Axunemi10. Persons associated with a place (including some professions) may also use -iy or -ey (pl. -éy):

Kuras Šura → kurázes Šurene

jadziac sculpt → jadzíes sculptor

uyku herd → úykes herdsman

Xurno → xurney11. Femininization: zim- or zin-. To be used sparingly; Xurnese is generally happy with unisex forms: šudzirc waiter, waitress; im prince, princess.

Inex → inexiy

jen forest → jeniy woodsman

rina river → riney ferryman

nye king → zinnye queen

šejis deer→ zinšejis doe

etešis whip → eteji a whip13. Collection: -ex (unacc.; pl. -as):

jivi walk → jiviji cane

rim weave → rimiji loom

dzučuc ritual → dzučuex book of rituals14. Study, thought, art (like -ism, -ology): -xau ‘study’:

mnaur wear → mnórex clothes

sim glyph → símex writing system

šuš bone → šúšex skeleton

Meša → Mešaxau Mešaism15. Language: -ši:

bej shoot → bejixau archery

xayu sky → xayuxau astronomy

Asunai → asunaši

kaym buy → kaynar store17. Lands are named with -nel:

šomis ship → šominar dock

bic grape → bicnar tavern

edi Wede:i → Edinel Wede:i-land

Puro a river → Pronel

kazi Caďinorian → Kazinel Caďinas

mes woman → mésuy big womanThe Axunašin suffix -i (pl. -w) has been borrowed or revived in some words:

jud hole → júcuy big gaping hole

nye king → nyei emperor19. Diminutive: -is (unacc.; pl. -isi):

japu goat → jápis kidFor mass nouns, the diminutive can be used to name the smallest discrete unit:

nye king → nyeis kinglet

nuna street → núnis alley

nis snow → nísis snowflake

ruywen grass → ruywénis blade of grass

zu sand → zúis grain of sand

1. Adjectivization -ri (voices previous consonant; -gri after n or x, -bri after m or w, -tri after s or c; l + ri → -rri):

nye king → nyeri royalThe same suffix serves to create a present participle from a verb:

xuma man → xumbri male

mayp mother → maybri maternal

kis grow → kistri growingand to form an adjective from a toponym:

sun dream → sungri dreaming

brešuac develop → brešuatri advanced (lit. developing)

Inex → inegri2. Another common suffix is -u:

Bolon → bolongri

Siyku Xengi delta → šiykuri

baj four → baju fourth3. The unaccented suffix -eš or -uš, deriving from the genitive, has been lexicalized to refer to composition or legal ownership.

Čeiy → čeiyu

dum hut → dumu homely

xus wonder → xumu wondrous

dax palace → dásiš royalFor nouns that were feminine in Axunašin , the suffix is -i:

nan god → náneš divine

jud hole → júdeš lace

šuke color → šuki colorful4. A past participle can be formed by adding the suffix -aup:

paup stone → pui stony

xule wood → xuli wooden

čiri cook → čiraup cookedThese adjectives are not pluralized: čiraup širvú ‘cooked vegetables.’

jese kill → jesaup murder victim

reus imprison → rosaup prisoner

5. Personal qualities are often adjectivized with -mel:

boru true → brumel truthful6. An adjective can be weakened with -is (unacc.):

jis weak → jisimel timid, tentative

rac justice → raymel justice-loving

yuc oil → yucmel schmaltzy

nulač sick → nuláčis unwell7. Quality of a noun: -moro:

rauj red → ráujis reddish

šum ugly → šúmis funny-looking

niu grace → niumoro graceful8. Follower: dzu-

nue cat → nuemoro like a cat

mes woman → mesoro womanly

nye king → dzunye royalist9. The suffix -ač forms a negative:

bayl dissipate → dzubayl hedonistic

ródeš popular → dzuródeš conformist

gec mind → gerač insane10. Patronymic. The clitic ma- (before a vowel, maz-) means son of, like Irish Mc- or Norman Fitz-; the female form is ne- (before a/e/o neg-, before i/u nes-).

rile see → rilač invisible

mojuri possible → mojurači impossible

Bezu ma-Veon Bezu son of Beon (Remember that b → v between vowels; ma-Veon is considered one word.)

Itep neg-Auliric Itep daughter of Auliric

cuš dance → cauč dance2. The process for creating a noun: -ac:

koma home → keum reside

yas hunt → yaš hunt

rema milk → remyac milkThe same suffix turns an adjective X into a verb ‘to make something X’:

pija filth → payjuac corrupt

jire wife → jireac marry

geun straight → gewmiac straighten3. Bestowal of an object or condition: -de:

bip small → biac abase

nus name → naunde give a name to4. The suffix -šis roughly means ‘use X’; with body parts it often has a despective meaning:

nar place → mride grant

xe body → xede create

gil stream → gilaušis ford5. Added to an adjective, the suffix -bes (which is simply the verb ‘become’) forms a verb with the meaning ‘become X’:

sou salt → solaušis add salt

raun tongue → raunešis slander, insult

jad butt → jadzišis move lewdly, live loosely

caun rotten → caumbes rot6. A negative can be formed with -ač-; this is sometimes a survival of the Axunašin negative mood, sometimes formed by analogy. This suffix is not very productive; it’s generally preferable to use the auxiliary sače instead.

rauj red → raujives redden

rues want → rugačis not want7. To undo an action, or remove something: o- (or- before a vowel):

zene know → zenače not know

gerizas understand → gerizagač misunderstand

sinde say → sindače not say

naušvar approve → onaušvar retract one’s approval

jireac marry a woman → ojireac divorce

šeguac bury → ošeguac disinter

rízex testicles → orizas castrate

Ir nevu jadzíes mnošuac.

my niece sculptor date-3s

My niece is dating a sculptor.To tir mayp mausiga kalayš.

3s.OBV 3s.GEN mother much please-3s.PAST

He pleased her mother very much.

S O V → S O V-Inf AuxIf there are additional constituents between object and verb (e.g. adverbs or prepositional phrases), they remain between the object and infinitive.Toš to ray do šasaup rile šizen.

3s 3s.OBV in no flaws see can-3s

She can see no flaws in him.

S O ... V → S Inf O ... Inf AuxThe Xurnese negative is an auxiliary, and follows this rule:To am šus bunji dis kes denjic.

3s.OBV one province some day govern hope-3s

He hopes one day to govern a province.

Syu cu šus izrues šač.

1s that province envy not-1s

Myself, I don’t envy that province.

Myes mavú, myes i mava, tas wéneš koros.The accusative form of pronouns is used with a postposition: toy eš against us.

2p.acc love.1s / 2p.nom 1s.acc love.3s / 1p happy family

I love you; you love me; we’re a happy family.

2s pronouns take 3s verb forms, and 2p pronouns take 3p verbs.

Sulayc li tir mayp mirileju; toš i šigosuac pel to šači.If the topic switches to the referent of to— in the example, if the speaker went on to concentrate on the boy’s mother— then toš is used instead. Thus, toš is used for the first of two named referents, or for the main topic of the conversation.

youth and 3s.GEN mother met-1s.past / 3s 1s.acc bore-3s but 3s.OBV not-3s

I’ve met the boy and his mother; he bores me but she doesn’t.

If a sentence contasts toš and to, it may distinguish the genitives otoš and oto. If ambiguity is not likely, tir should be used.

Verbs of personal grooming are understood to be reflexive if no object is specified: Laumijú I washed myself.

Reflexives can never be used (as in Verdurian or Spanish) for an impersonal meaning (se habla español).

With plural referents, the reflexive always indicates that each person acted upon himself. The expression ceš playnu ‘this one the other’ indicates a reciprocal meaning. Compare:

Kyes kyes tirse jesejayc. They each killed themselves.

Kyes kyes čes playnu jesejayc. They killed each other.

The expression ros ‘people’ can be used much like an indefinite pronoun. In colloquial speech ros is often omitted, leaving an impersonal 3p verb.

(Ros) yajirc tom Yajirc naundayc.Tas ‘we’ can be used as an inclusive impersonal expression: Tas toš Yajirc naundom We call him Hunter. Similarly myes ‘you’ can be used to refer to the listener’s people: Myes toš ‘yagom’ naundayc You (Verdurians) call him ‘Yagom’. This impersonal myes is always distancing; don’t confuse it with the informality of English impersonal you as in You know how women are.

(people) hunter to ‘hunter’ call-3p

They call the hunter ‘Hunter.’

Impersonal rile ‘see’ is used as an existential, rather than ize:

Buma edumi rilayc, li palači am zú.

two idiot.PL see-3p / and only one be-1s

There are two idiots here, and only one is me.Niormen ray cu mavije na moz rilejuc.

Niormen in that love-PAST.1s SUB girl see-PAST.3p

There was a girl in Niormen that I loved.

The cardinal numbers are not declined: am yeys one feather, seči dim six days. Ordinals are regular adjectives and have plural forms: puc runi the second city, pucú runú the second cities.

cardinal ordinal +10 x10 1/x 1 am im andeš deš 2 buma puc bundeš pudeš teyeš 3 dzi dzim dzayndeš dzideš 4 baj cidzi bandeš cideš sumiš 5 peyk peykaur peygudeš peydeš 6 seči seyčaur semudeš sedeš 7 šic šizaur šimudeš šideš 8 yauš yusaur yumudeš yudeš 9 nep neyvaur naymudeš nedeš 10 deš deysaur sigac

Two-digit numbers are formed by concatenation (cidešdzi 43, šidešyauš 78) except for those with final 1, which becomes -mam (a survival of Ax. mu): pudešmam 21, and -6 which becomes -šeči.

Names of the hundreds use the same prefixes as the tens: pusigac, dzisigac, etc. Thus peysigač šideššeči 576.

Ezir ‘1000’ however is a separate word: seči ezir 6000.

Higher ordinals are formed by changing the last digit only.

Years are reckoned from the foundation of Xurno in 2530 (buma ezir peysigac dzideš); the current year, Z.E. 3480, is thus 950 (nesigac peydeš). Sometimes years are counted from the Revaudo revolution (3017), making the current year 463 (cisigac sedešdzi).

Thus mes cumoro like a woman, rile eyka in order to see, bes rano along the road, Xurno ray ‘in Xurno’; cu rum eči dmuro during that long summer. The Axunašin adverbial suffix -iwa survives in Xurnese as ga, but has been reinterpreted as a postposition: rey ga ‘newly’, dam ga ‘smoothly’, gisu ga ‘importantly’. It can apply to other postpositions, to indicate a direction: neyo ga ‘across’, ray ga ‘inward’, etc.

postposition gloss cumoro like, as dmuro during dzu between, among, on dzus after; in back of dzušši since e to, toward eš against eši back to eyka for, in return for ga in, at, in the manner of leš in front of mu with mutes despite nao about, on ney over, above neyo across, beyond, except o of, out of, from ortes far from peš near, around pip before (in time) pišši until rameyn using, by means of rano through, along ray in, into šaup under, below tes without tom to (marks indirect object) xur beside, next to

Ga can be applied to nouns as well. It is used with the plural form, though no plural meaning is intended:

rilúšeč appearance → rilušeš ga in appearance, seemingly

nox night → nozú ga at night

šec experience → šedzú ga in (our) experience, as experience shows

Possession is indicated using o, thus: Deru o dus Deru’s house. Colloquially the genitive pronoun may be used instead: Deru tir dus Deru his house.

Tom indicates the indirect object:

Šudzirc nízeš jerej kaymirc tom dej.

waiter nutty bag customer to give-PERF

The waiter gave the customer a bag of nuts.

conjunction gloss li and ma(t) or pel but caunga rather, preferably ciluk because citun for this reason, therefore cutun for that reason, therefore jidil as a result, because of this keno if / then luk so, therefore mucauč also, in addition peyga on the contrary, however dzunyo and then, afterwards

nu li podi cats and dogsThe series can be extended if desired: nu li pido li japwe li rec cats and dogs and goats and rabbits.

baj ma peyk zinaup four or five articles

šizengri pel yucmel ševarirc an able yet cloying writer

Pidú bídeš caunga ricuka. I drink wine rather than rye beer.

Yes caučayš jidil yes neymoreji. You danced and then you slept.

There are eight inflected forms, not counting the infinitive:

Form Example Gloss Indicative Present Aycorú I am reading Perfect Aycaurijú I read (finished reading) Past Aycauriji I was reading Future Aycauriye I will read Subjunctive Present Aycaurimú I may be reading Perfect Aycauruswe If only I read Past Aycaurimije I may have been reading Future Aycauranye I may read (later)

Pečrešey yes lešrilen.In an emphatic sentence, the subjunctive alone expresses a wish:

editor you receive-3s.FUT.SUBJ

The editor may receive you (but probably won’t).Berdura brešuatri ros šu.

Verduria advanced nation be-3s-SUBJ

It’s said that Verduria is an advanced nation.Caučircú ammavri šuayc ma?

dancer-PL monogamous be-3p-SUBJ Q

You say dancers are monogamous??

Cu mul buma na pečrešey xauč šu!More typically, the subjunctive is used with auxiliaries or in subordinate clauses to suggest that the described state is hypothetical, wished for, or doubtful.

that fat cow SUB editor dead be-3s-SUBJ

I wish that fat cow of an editor were dead!

Ševarirc maus niudo mu ci elas ševarij, cu tas cuš aycaurimum eyka.

author much kindness with this lines write-3s.perf SUB we that read-1p.SUBJ for

The author very kindly wrote these lines in order that we might say them.Cu myes geun miw mu li geun ximaudo mu aycauryeyc citun bezzú.

that you correct words with and correct order with read-3p.SUBJ therefore beg-1s

I beg of you, then, that you say them with the right words and the right order.

The auxiliary is inflected, while the formerly main verb appears in the infinitive, just to its left. The subject, object, and any adverbials that are present are not affected, and in effect are shared by both verbs.

Auxiliary Negative Gloss Full Subordination šače negative no denjidze hope, expect to subjunctive šizene šizenače can, is able to no zene zenače know how to no rae rače habitually do no rues rugačis want to subjunctive xame xamače intend to subjunctive meuš mojač may, might no šaras šaragače must, have to no imiše imišače begin to no jidze jidače passive no

Yes mavyú → Yes mavis šač.Naturally, the auxiliaries may appear in the subjunctive.

you love-1s → you love-INF not-1s

I love you → I love you not.Maysu xivije → Maysu xip zeneji.

iliu swim-3s.PAST → iliu swim-INF know-3s.PAST

The iliu was swiming → The iliu knew how to swimCi sus o dzuzovugeš dzulé xu ize meuš.

this year of play-PL most bad be-INF may-3p

This year’s plays may be the worst ever.

Berdursú xudimayc → Berdursú xude raimayc.The subjunctive softens the meanings of certain auxiliaries: zene ‘know how to’ → ‘know a bit how to; xame ‘intend to’ → ‘think about doing’; šaras ‘must’ → ‘should’.

Verdurian-PL cheat-3p.SUBJ → Verdurian-PL cheat-INF go-3p.SUBJ

They say the Verdurians are cheating → They say Verdurians habitually cheat.

Šukeac zenidú. Jadziac šarasidú.

paint-INF know-SUBJ.1s / sculpt-INF must-SUBJ.1s

I can paint, more or less. I should do sculpting.

Pipaup berdursu riju ray orkime šačum.Šače is optional if other negative words are present.

drunk Verdurian room in hide-INF not.1p

We are not hiding a drunk Verdurian in the room.

Toš inar duoyo (zi / ize šuči), cu xunj na grišnar ray cinar nudzú.Sentences with auxiliaries are negated by using the negative auxiliaries (which are highly irregular; see the morphology section).

3s here never (be-PAST.3s / be-INF not-PAST.3s) / that snore-3s SUB closet in there point-1s

He has never been here, especially in that closet that is snoring there.

Maysu xip šučuc → Maysu xip zeynučuc.In English we can distinguish between negating the auxiliary and the main verb: I don’t know how to get noticed vs. I know how to not get noticed. This distinction is not usually made in Xurnese; the negative auxiliaries only negate the auxiliary itself. (It’s possible to use the -ač- suffix to negate any verb, but this is rather hifalutin, like coining a word: I know how to get unfamous.

iliu swim-INF not-3s.PAST → iliu swim-INF not.know-3s.PAST

The iliu wasn’t swiming → The iliu didn’t know how to swim

Xauč ize denjidzú.Denjidze ‘hope to’ does not have a negative form; but the subordinated clause can be negative.

dead be-INF wish-1s

I wish to be dead.Cu ir emu xauč šu na denjidzú.

that my husband dead be-3s.SUBJ SUB wish-1s

I wish my husband were dead.Ir šebreč imprimis xam.

my book print-INF intend-3s

He intends to publish my book.Cu xamunar ir šebreč imprimide na xam.

that salon my book print-3s.SUBJ SUB intend-3s

He intends for the Salon to publish my book.

Deru yu šuema imise zene rap.Uneducated speakers are known for conjugating all the auxiliaries rather than just the last one:

Deru good beer find-INF know-INF habitual-3s

Deru always knows where to get good beer.Ševarirc toy grijil xame mojači.

writer us confuse-INF intend-INF may-NOT-3s

The writer may not intend to confuse us.Cu šebreč aycaur rae xameju, pel i šigosuac.

that book read-INF habitual-INF intend-PAST-1s / but me bore-3s

I was fixin’ to keep reading that book, but it’s boring.

Toš imise zenú mojú.

3s find-INF know.how-1s may-1s

I might know how to find him.

Ci kasum oyes euma e čeji.Colloquially, the present tense may be reduplicated to form an imperative:

this basket your grandmother to take-INF

Take this basket to your grandmother.Wes e xuxame pel teris.

artist to approach-INF but be.silent-INF

Approach the artist but be silent.

Ir emu ujú— ra ra!Xurnese does not have the wide range of softened pseudo-imperatives that English does. When an imperative is softened, it is normally by use of diminutives:

my husband hear-1s / go-3s go-3s

I hear my husband— Go!

Déruis, bic i de.Commands were given using the future and subjunctive, as in Axunašin, until the Revaudo revolution, when these usages were seen as hopelessly class-ridden. They still survive in some remote provinces (generally the same ones which still use the ‘royalist’ pronouns).

deru-DIM / grape me give-INF

Deru darling, pass me a grape.

Ševarirc wéneš. Tir šebreč makri. Yes izruirc.It reappears in other tenses: Tir šebreč makri zi ‘His book was successful’.

writer happy / 3s.GEN book successful / 2s envious

The writer is happy. His book is successful. You are envious.

The constituents can be swapped:

Wéneš ševarirc. Makri tir šebreč.In the first person the verb is still required in the written language (Wéneš zú I am happy), but in colloquial speech it’s omitted (Syu wéneš).

happy writer / successful 3s.GEN book

Happy is the writer. Successful is his book.

The verb is not omitted in impersonal expressions: mojurači ze It’s impossible.

Ize is not used as an existential; see Impersonal expressions.

Peje ‘stand’ is used colloquially to express one’s current or temporary state; thus Wéneš pejú I’m happy right now, Toš braup pej He’s busy at the moment. It’s also used for time expressions: Nimala peje It’s market day.

With the past participle (not the infinitive) and in the past tense, peje indicates that the events described occurred at an earlier time, much like the English past perfect.

Jorumíex omeunijayc, pel jošmir oraup pejeji.

council deliberate-PAST.3p / but opportunity leave-PP stand-PAST.3s

The council deliberated, but the opportunity had past.

1. By intonation alone

Yes xuxaleš?2. By appending the conjunction ma:

2s crazy

You’re crazy?

Yes šuema imisej ma?3. By appending the phrase ma jende ‘or how’, the origin of the previous form:

2s beer find-PERF.3s or

Did you find the beer?

Berdursu ez šuema picayš ma jende?4. Using jic before the verb— an inheritance from Axunašin jiti:

Verdurian every beer drink-PERF.3s or how

The Verdurian didn’t drink all the beer, did he?

Muré nanú dmuna jic gemayc?Questions usually use the indicative, but the subjunctive can be used instead to suggest that the suggested state is absurd or unlikely.

Muran-PL god-PL still Q accept-3p

Do the Uṭandal still believe in gods?

In writing it’s still normal to respond to questions as in Axunašin, using the verb (imisejú I found it); but colloquially one responds cunde ‘that way, yes’, šači ‘it isn’t’, or donde ‘no way, not at all’.

Ir jira tom jiváteč nao ji bausij?The use of the subjunctive implies that what is questioned may not exist, or is unlikely to be known:

my wife to liquor about who tell-PERF-3p

Who told my wife about the liquor?Xauč peš pišši je etešayš?

dead near until whom whip-PAST-3s

Who did she whip senseless?Xamunar o rireširc jideym xam?

salon from inspector when come-3p

When is the inspector from the Salon coming?Mes i cunde tun rešeji?

woman 1s.ACC that.manner why look-PAST.3p

Why did the woman look at me like that?

Peranagu e bes jinar šu?In this case the subjunctive signals the absurdity of the question: Fananak is across the ocean, so there is no road there.

Fananak to road where be-SUBJ.3s

Where is the road to Fananak?

There are some dialects where interrogatives appear where the corresponding NP would: Ji i čaujeji? Who touched me? This sounds unutterably rustic to anyone from the Xengi valley.

Yes xaušmelač luk oraeyu.(See also Coordination subordination below.)

2s disrepectful therefore leave-1s.FUT

Because you are disrespectful, I will leave.

subj S1 keno subj S2For past conditions, use the past subjunctive; there is no tense substitution as in English:Oyes mavirc xamim keno, zenaup ga kejideym šu.

your lover come-3s.SUBJ if / certain ADV dinner be-3s.SUBJ

If your boyfriend is here, it is surely dinnertime.

Ševarirc xorneacaux keno, tir emur jecaux.As there is no negative subjunctive, negative conditions and consequences are simply expressed using the negative auxiliary:

writer err-3s.PERF.SUBJ if / 3s.GEN husband laugh-3s.PERF.SUBJ

If the writer had made a mistake, her husband would have laughed.

Kissu i raunešis šuči keno, syu toš yalu eš nejlaj šuč.For logical consequences of sure facts, Xurnese doesn’t use keno but simple conjunctions such as cutun ‘therefore’:

child 1s.ACC insult-INF not-3s.PAST.SUBJ if /

1s 3s.ACC knee against kick-INF not-1s.PAST.SUBJ

If the boy had not insulted me, I wouldn’t have kicked him in the knee.

Pudis peje, cutun Rajjay ray izom.

second-day stand-3s / that.reason Rajjay in be-1p

It being the second day of the week, this must be Rajjay.

S O V → to O VThe singular equivalent isn’t *Toš toš zic, but uses the obviative: Tos to zic or To tos zic. It’s also possible to pronominalize with ceš ‘this one’ or cuš ‘that one’, especially with inanimates, or when making contrasts between two referents.

→ S to VPečrešéy ševarirc ziduc.

editor-PL writer hate-3p

Editors hate a writer.→ Kyes ševarirc ziduc. They hate a writer.

→ Pečrešéy toš ziduc. Editors hate him.

→ Kyes toš ziduc. They hate him.

Deru buma mozú mnošuac. Ceš zimaysu, li cuš isaur.

pname two girl-PL date-3s / this.one pretty and that.one smart

Deru is dating two girls. One is pretty, and the other is smart.

S O V → S O V-infThe infinitive expression can be used as a predicate, where we would use a subordinated impersonal expression:

Xamunar ir šu gemej. → Xamunar ir šu gemi

salon my uncle admit-3s.PAST → salon my uncle admit-INF

The salon admitted my uncle. → the salon admitting my uncle.

Xamunar ir šu gemi mojuri.Or it can be used as an argument to a verb:

salon my uncle admit-INF possible

The salon admitting my uncle is possible,

or, It’s possible that the salon admitted my uncle.

Xamunar ir šu gemi buguc.If the infinitive expression is used as the object, the subject must come just before the verb; Xamunar ir šu gemi Inex baus Inex is talking about the salon admitting my uncle.

salon my uncle admit-INF talk-3s

They’re talking about the salon admitting my uncle.

The imperative, discussed above, uses the infinitive transformation.

S O V-morph → S O V-Inf Aux-morphCu xušimirc etešip → Cu xušimirc etešis šarasiye.

that upstart whip-FUT.1s → that upstart whip-INF must-FUT.1s

I will whip that upstart → I’ll have to whip that upstart.

Xamunar ir šu gemej. →These postpositions must be used with pronouns as well: toš nao gemaudo his admission. (Don’t use the genitive: *tir gemaudo.)

salon my uncle admit-3s.PAST →

The salon admitted my uncle. →Xamunar nao ir šu e gemaudo

salon about my uncle to admission

the salon’s admission of my uncle

x (y z V1) V2 → x cu y z V1 na V2An entire sentence can serve as the object or subject of the verb.

(y z V1) w V2 → cu y z V1 na w V2

Cir šemilircú cu zešnasú boru ga Cuwoli ray reatuc na gejayc.As noted above, the subordinated clause appears in the subjunctive if it is not a matter of fact.

our agent-PL that Dhekhnami-PL true ADV Cuoli in move-3p SUB tell-3p

Our agents report that the Dhekhnami are indeed active in Cuoli.Cu yes šwedze xam na i xušim.

that you argue-INF intend-3s SUB me amuse-3s

It amuses me that you wish to argue.

With verbs of speaking or thinking, the subject is normally moved before the verb.

Cu braunic mavis na šuč na geyma sindej.This is indirect speech, and tenses match the narrative (e.g. the lady spoke in the past, so ‘love’ is also past). Direct speech omits the initial cu and replaces na with cuš ‘that’:

that truth love-INF SUB not-PAST.1s SUB lady say-PERF.3s

The lady said I did not love the truth.

Píješ xaundirc ze, geyma cuš sindej.

filthy liar be-3s / lady that say-PERF.3s

The lady said, “You are a filthy liar.”

Yes xaušmelač luk oraeyu.However, it’s also possible to highlight the subordination by enclosing the subordinate clause within a cu...na block. Formally this turns the conjunction into a postposition, and the subordinated constituent normally moves after the subject (and object if any) in the sentence:

2s disrepectful therefore leave-1s.FUT

Because you are disrespectful, I will leave.

S1 conj S2 → S2 O2 cu S1 na conj V2It’s difficult to suggest the same effect in English; stylistically, the subordinate clause is less important, more of an adverbial comment than a structured logical argument. At the same time it’s more integrated into the sentence, and feels less spontaneous, more bookish.Cu yes xaušmelač na luk oraeyu.

that 2s disrepectful SUB therefore leave-1s.FUT

I’ll leave, since you are being disrespectful.

S O1 V1 & S O2 V2 → cu O1 V1 na S O2 V2A clause is relativized with the cu..na block:S1 O V1 & S2 O V2 → S2 cu S1 V1 na O V2

Cu am breši ma na xuma ir jira jesej.Ci ‘this’ may be used where additional information is being offered about someone already referred to.

that one arm have-3s SUB man my wife kill-PERF.3s

A man with one arm killed my wife.Cu toš popej na breš dmuna mú.

that he lose-PERF.3s SUB arm still have-1s

I still have the arm which he lost.

A clause cu NP V na is ambiguous between a reading where the NP is the subject or the object: cu mes jesej na could mean that killed a woman or that a woman killed. The clause can be disambiguated by including the obviative pronoun to in place of the relativized argument: cu to mes jesej na that killed a woman, cu mes to jesej na that a woman killed.

The use of to allows a constituent from a doubly embedded clause to be relativized; this can’t be done in standard English.

[Xuma dzuzovúgeč ševarij] [Jorumíex dzuzovúgeč empojačiji] xuma ilirileju →A relative clause may include another:

man play write-PERF.3s / council play disallow-PAST.3s / man meet-PAST.1s

[the man wrote the play] [the Council banned the play] I met the manCu Jorumíex cu to ševarij na dzuzovúgeč empojačiji na xuma ilirileju.

council play disallow-PAST.3s / man play write-PERF.3s / man meet-PAST.1s

*I met the man who the Council banned the play he wrote.

Cu Inex ray keume na mavirc mnošuac na xaircCu is not reduplicated. If it’s desired instead to subordinate multiple clauses to the same noun, use a conjunction:

that Inex in live-3s SUB girlfriend date-3s SUB student

a student who has a girlfriend who lives in Inex

Cu Inex ray keume na li mavirc mnošuac na xairc

that Inex in live-3s SUB girlfriend date-3s SUB student

a student who has a girlfriend and who lives in Inex

E O V → S cu O V-inf E-acc na dem-morphCausatives use the same verb as Axunašin, de ‘give’. The caused action is placed in a cu..na block, the verb appearing in the infinitive.

Yojaup rindeju. →Empeuš ‘allow’ uses the same construction, as do yac ‘command’, ruje ‘force’, ruzene ‘ask for’, and many others.

nude draw-PERF.1s →

I sketched the nude. →Zendey cu syu yojaup rinde na dayš.

teacher that 1s nude draw-INF SUB give-PAST.3s

The teacher made me sketch the nude.

Syu cu bunji yojú ir emu rile na empeuš šač.The causer may be left out (taking cu with it). The resulting sentence suggests impersonal causation or a lack of responsibility:

I that some nude-PL my husband see SUB allow-INF not-1s

I don’t allow my husband to see any nudes.

Syu yojaup rinde na dayš.Front the object (as described below), and we have something close to a passive:

1s nude draw-INF SUB give-PAST.3s

I was made to sketch the nude.

Yojaup syu cuš rinde na dayš.The subject may now be omitted, and the verb changed to jidze ‘suffer’, for an impersonal passive:

nude 1s that.one draw-INF SUB give-PAST.3s

The nude was sketched by me.

Yojaup rinde na jidzeji.There is a negative passive jidače.

nude draw-INF SUB suffer-PAST.3s

The model was sketched.

Cu mulayc pec na cideym aujikulur mum.Indefinite pronouns can be used as well; compare the meaning of the last example with various pronouns substituted for cinar:

that fat-person sing-3s SUB then musical have-1p

When the fat woman sings, we have opera.

Cu kešaup dzuséy kejačejuc na cinar kejeyu.

that separated master-PL eat-PAST.3p SUB there eat-FUT.1p

We will be eating where the Hermit Masters fasted.

inar → We will eat here where the Hermit Masters fasted.Such an adverbial can be subordinated to a noun.

donar → We will eat in no place where the Hermit Masters fasted.

amnar → We will eat some place where the Hermit Masters fasted.

eznar → We will eat everywhere the Hermit Masters fasted.

Neyosu šigri ga cu Yute mirile denjidzeji na pucišnar imisej.No pronoun is generally used; but if it’s unclear whether the subclause indicates when something happened, or where, or even why, the pronoun can be included inside the clause:

foreigner difficult ADV that Yute meet expect-PAST.3s SUB atelier find-PERF.3s

With difficulty, the foreigner found the Atelier where he was supposed to meet Yute.

Neyosu šigri ga cu Yute cinar mirile denjidzeji na pucišnar imisej.A time expression can also be subordinated to a postposition, e.g. dmuro ‘during’, dzus ‘after’, dzušši ‘since’, pip ‘before’, pišsi ‘until’:

foreigner difficult ADV that Yute there meet expect-PAST.3s SUB atelier find-PERF.3s

Cu joraumirc xamey na pišsi keji šačum.Idiomatically, peje ‘stand’ plus a subordinated dzus clause expresses that something has just happened, and with a pip clause that it is just about to happen:

that councillor come-FUT.3s SUB until eat-INF not-1

We will not eat until the Councillor arrives.

Cu ir gejúpuy tasije na dzus pejú.

that my novel finish-PAST.1s SUB after stand-1s

I’ve just finished my novel.

Cu oyes endevausirc ize na gesauliri zú.

that your mentor be-INF SUB proud be-1s

I’m proud to be your mentor.

Cu yes sor na wogri zú.

that you hurt-INF SUB sorry be-1s

I’m sorry that you are in pain.

S O V → O S cuš VNormal constituent order is SOV; the direct object may be fronted if cuš ‘that one’ is left in its place. Objects are normally fronted to topicalize them.

Ir jira ci jadzíes toy koma e mneušije.The object of a postposition can be fronted in the same way; note that the postposition is duplicated, appearing after both the fronted object and the inserted demonstrative.

my wife this sculptor our home to invite-PERF

My wife invited this sculptor to our home.→ Ci jadzíes ir jira cuš toy koma e mneušije.

this sculptor my wife that.one our home to invite-PERF

This sculptor, my wife invited him to our home.

→ Toy koma e ir jira ci jadzíes cuš e mneušije.Indirect objects are postpositional phrases and work the same way:

our home to my wife this sculptor that.one to invite-PERF

Our home, my wife invited the sculptor there.

Kaymirc tom šudzirc nízeš jerej cuš tom dej.

customer to waiter nutty bag that.one to give-PERF

The customer, the waiter gave him a bag of nuts.

S O V → S V OAn NP or postpositional phrase can also be moved to the end of the sentence; this generally highlights the constituent, for drama or to express suprise or shame.

Roc xayórex šaup imisejayc xa.It’s even possible to back a constituent from inside a subclause:

people pavement under found-PERF.3p corpse

Under the pavement they found a corpse.

Šonuatirc cu alui o raun andeym šudziac mojuri na zeniseji.A sentential subject or object may be backed, leaving cuš in its place and omitting the initial cu. Leave the final na for direct speech, omit it for indirect speech (or, in first person, a slight softening effect).

detective that lark of tongue sometime serve-INF possible SUB ask-PAST.3s

The detective asked if they had ever served lark’s tongue.→ Šonuatirc cu andeym šudziac mojuri na zeniseji alui o raun.

→ detective that sometime serve-INF possible SUB ask-PAST.3s lark of tongue

Wogri ga yes cuš baus šaragú, ci ravom pija na.

regretful ADV you that.one inform-INF must-1s / this canvas filth SUB

I must regretfully inform you that this canvas is shit.

We can declare that ‘girls’ are a natural class and pretend we’re done, but the concept of a ‘natural class’ doesn’t really hold up. For one thing, classes are vague... when exactly does a moz become a mes, a woman? Worse yet, classes depend on culture and language. The Axunemi, who maintained that there were three sexes, had a different idea of ‘girl’ than the modern Xurnese. Even where boundaries seem clear (a kissu ‘child’ is not marriageable, a moz is), they end up permeated by culture— e.g. the age of marriage depends on historical epoch, region (it’s higher in the cities), and even ecology (in bad times marriage is delayed).

A key insight of Saussure was that the whole problem of single-word meanings could be sidestepped by looking instead at language as a structure. Meanings don’t exist in isolation; they’re circumscribed by their relationships with other words.

It’s worth noting that all cultures have categories; but not all emphasize them as we do. Premodern peoples—including the majority of Xurnese— tend to associate things by function, not category. Asked to find the subgroups within the set nue cat, red rabbit, teyp knife, the modern mind groups nue and red together as nečidircú mammals; the premodern groups red and teyp together on the grounds that knives are used to skin rabbits.

An obvious example is irony: a speaker says Yes susaur You’re brilliant to mean the opposite. Sometimes an ironical meaning is even lexicalized: e.g. the Mešaic term šuvičik ‘seek enlightenment’ was used ironically so often by the Endajué masters that šwečis now simply means ‘to be spiritually confused’.

Phatic communication is used to reinforce social bonds rather than convey information. For instance, English How do you do? is not a request for a medical diagnosis, it’s a greeting; the same is true of the Xurnese equivalent Maypayvú yunú?, literally Your parents are good?

We may also distinguish an utterance from a sentence. An utterance is a single speaker saying something, at a particular moment in time, in a particular context. This gets so messy that linguists and logicians prefer to deal with sentences, abstract statements without context. The optimist hopes that by getting the abstract sentence right, we’ll be in a better position to plunge into the grimy specifics of utterances. The pessimist may feel that focussing on ‘sentences’ is so artificial as to be counter-productive. If we want to learn how humans use language, we won’t get far by throwing out most of our subject matter.

We will focus on the interaction of language with the world under Pragmatics below.

It’s evident that words are much more complicated beasts than they look like in the dictionary. We deal seemingly effortlessly with a large mass of information about each word:

There are often idiosyncratic ways of referring to associated words: e.g. birds and sheep come in flocks, cows come in herds, fish in schools. In Xurnese domestic animals (e.g. cows or sheep) come in uykú, while small animals that move in unison (e.g. birds or fish) do so in ambrigas.

We can often find out more and more about a word’s meaning just by looking closer; George Lakoff wrote a 46-page analysis of the single word over. This gets into knowledge of the world; but there’s no firm boundary between knowledge about the word and knowledge about the world.

Another naive formulation is that all the members of a class have “something in common”, even if we are not sure what it is; Wittgenstein pointed out that this is not the case for many words, such as game, whose instances have family resemblances but do not all share a set of features. (This is even more true of šudo which also covers the ground of play, fun.)

Grammarians generally go farther; the morphology and syntax sections of a grammar are essentially the language’s operators, with the predicates and arguments left to the lexicon. But the lexicon is not merely a list; we know quite a bit about each word. (Foreign-language lexicons such as the one attached to this grammar are brief because they omit many complications, and because by providing glosses they leverage our own real-world knowledge.)

Syntacticians in the 1970s produced ‘semantic structures’ based on predicate calculus; e.g they would relate

Itep sukirc jeseji.to

Itep rapist kill-PERF.3s

Itep killed the rapist.

CAUSE(Itep, DIE(rapist))Some went on to treat nouns as predicates, leading to something like

EXISTS x, y SUCH THATPerhaps the same meaning underlies other sentences: e.g. The rapist was killed by Itep has the same semantic structure, but undergoes an additional transformation; Did Itep kill the rapist? has the same structure plus an element Q which queries truth value.NAMED(x, “Itep”) &

RAPES(y) &

CAUSE(x, DIE(y))

Many an ambitious grad student felt that, with just a few more semesters of work, the appropriate transformations could be modelled in LISP.

It’s worth playing with, just to see how far it can be taken. But as a model of either meaning or how the brain processes language, it’s at best very incomplete.

On Tuesday Itep caused the rapist to die on Thursday.

*On Tuesday Itep killed the rapist on Thursday.

amevati make one → ameac have sex +

ujivateč story → aujateč evidence +

pideč song → pídeč hymn (religious song)

revaudo newness → name of a religious awakening

šedirti sufferer → šedirc sick man

tibiki feel somewhat → civike pity

ewis world → wec milieu

yósuc tailored outfit → blouse

benki bless → beyk support

kezi command → kes govern

mexi mistress → mes woman

seješ clock → seješ machine

Šinkou the Xengi delta → šiyku any river delta

niwo grace → niwo gentleness

nugišik swallow → naušis suck

pavičik kiss → payčis embrace

puč stomach → puš abdomen +

rišidem lift → rešide get drunk

weš tail → weš buttocks

yaz cheek → yas mouth +

cue pour → host

miswen muscle → thug

rogu prison cell → rosik prison +

šuke color → tempera +

sagi sleep with → sas impregnate

kuzun a wonder → xuzu an attraction

makuri conquering → makri successful

wogi feel horror → weus regret

xul evil → xu bad

kokem knock → koke beat up +

suki pierce → saus rape +

sisikim annoy → sizike injure

zidi shudder → zic hate

baili amuse oneelf → bayl be dissipated

doumun domestic → dumu homely

meidemax peasantry → mídzex rabble

podei dog → podze rascal

ranaxun magical → ransu creepy

gi boy → xiu servant

us nose → up snout

zočuri different → zočaur heretical

dauxevi teacher → dzusey master, guruThere are also changes that simply reflect arbitrary changes in society:

demujidim await → denjidze hope

pojem drive animals → poje oversee

račazi whore → račaze entertainer

ewez a member of the third sex → intellectual → wes artistThe replacement of Mešaism by Endajué resulted in many Mešaic terms being reinterpreted negatively:

yaginari hunting preserve → yasinar retreat, spa

menalun of Mnau → mnalu outlandish

dzunan polytheist → bastard

nanudič child of two gods → nándzeš monster

šuvičik rise spiritually → šwečis be spiritually lost

duzočus rite → dzúčuc superstition +

čuzis fall apart → lose (a battle)One continuum may be likened to another; this provides terms for the extremes and sometimes points in between:

ejize poke → have sex

jisimel craven → tentative

kissu seedling → child

nudzis point → refer

orae leave → happen

peje stand → be (in a state)

šonuac spin thread → deduce

šwepusi fall short → disappoint

yucmel oily → cloying

Even more productive are metaphor systems, which can generate many expressions and be extended by speakers. Some examples common to Xurnese and English:

HEAVY IS IMPORTANT gisu heavy, important tegisu light, unimportant SHARP IS SMART isaur sharp, smart širi dull, dumb SOFT IS MERCIFUL mul soft, merciful dor hard, mean

LIGHT IS WISDOM

aul bright → clear

auliac brighten → explain

beriludo cloud-seeing → illusion

beyru cloudy → obscure

siluri brilliant

xorneac darken → make a mistake

HIGH IS IMPORTANT

bez low → humble

neymoro above → major

rešayc tall person → boss

šaumoro below → minor

SEX IS CONQUEST

mase conquer → seduce

nejasu soldier → ladies’ man

reuni besiege → pay court to

xauke skirmish → make a pass

ARGUMENT IS FIGHTING

šwedu mase win an argument

šwedu čuzis lose an argument

čaš opponent

ešinde counter, parry

A BUILDING IS A BODY

breš arm → wing

leš face → façade

dzuc back

teyš chest → main structure

mnórex clothes → decoration

giarji finery → rococo decoration

jiwe spine → main beam

tile rib → supporting beam

LARGE IS NUMEROUS

dari large → numerous

bip small → few in number

FEMALES ARE WATER

myun watery → effeminate

kagas dry → chaste (of males), impotent

rinari like a river → graceful

MALES ARE EARTH

sustri earthy → machoIn early Xurno, solidarity against the barbarians was an essential virtue; one of the key metaphors was THE EMPIRE IS A FAMILY. (This can be traced back to Axunai, but it was much more marginal; Axunemi absolutism was not very paternalistic.) The emperor referred to both cities and subjects as his children; he was called payp father and his policies approved as payvaur paternal. The Revaudo revolution countered this with a new metaphor THE EMPIRE IS A PREDATOR; this underlies the slang term ricayc royalist (= ‘wolfish’) as well as the verb riciac oppress = ‘act like a wolf’.

saumes earth-lady → lesbian

Other Xurnese metaphor systems which are not used in English, or used less extensively:

AN ARMY IS A BODY

newe brow → general

juysu head → commander

teyš chest → colonel

pučisu belly → major

reyxu thigh → lieutenant

xuc leg → sergeant

neja foot → infantryman

breš arm → vanguard

waysu nose → scoutThe movements of the body are also used for armies: neymore sleep = camp, jivi walk = march, etc.

The internal organs are used for nonce meanings, but these have not been lexicalized, except for the general xímex organs → support staff.

ARGUMENT IS ARCHITECTURE

Some of these derive at one remove from another metaphor system (A BUILDING IS A BODY).šwedu eši make an argument

dumu rickety → weak

gedzáysuš structurally sound

riykuirc bird’s nest builder → crackpot

cuystri leaky → full of holes

dax palace → proof

gij column → premise

šeyka roof → conclusion

puc floor → stage, step

teyš body of an argument

breš wing → side discussion

jiwe spine → crux of an argument

giarji rococo decoration → rhetorical excess

THE COSMOS IS A DANCE

cauč dance → cosmos

caučirc dancer → creature, spirit

bodeusis walk lamely → be foolish

reatudo movement → flux, fortune

rináric grace → acceptance of one’s fortune

WRITING IS DANCE

reátuc step, motion → action

reatudo motion → plot

brešísuc gesture → trope

MORALITY IS A PATH

ende path → morality

tegendi pathless → damned, depraved

jivirc walker → believer

pope drive (animals) → pastor (people)

misustri muddy → morally difficult

bem ga like a road → morally clear

WAR IS A PAINTING

nelima frame → context, casus belli

rímex sketch → strategy

šonasudo brushwork → tactics

ravom canvas → battlefield

šuke paint → blood

A SWORD IS AN ARM

uyk nail → edge

meyn hand → blade

xuba elbow → grip

néybreš upper arm → hilt

manyuma puff sleeve → basket hilt

SEX IS A RIVER

notanelu parched → lustful

ameatudo confluence → sex

ri flow → become excited

šiyku (imise) (reach the) delta → orgasm

xiaz ocean → post-coital happiness; sexual happiness in general

SEX IS A PAINTING

šónex brush → penisI’ve emphasized lexicalized metaphors here, but most of these metaphors are productive and can be used in phrases as well, e.g. ende pope lose the path → go wrong.

ravom canvas → vagina

šukeac paint → have sex

šuke paint → semen

He went further, identifying basic metaphors said to underlie our cognition, each based on direct bodily experience. E.g. the act of categorization itself is said to be a metaphor CATEGORIES ARE CONTAINERS.

We can zoom in to a smaller extent and treat the components of an object as entities: neywen o leš the front side of the bed. If an object’s plexity is changing, we can take the point of view either of the whole (Bumu ga paup čuzije The rock broke in two) or the pieces (Paup o teš čuzijuc The two halves of the rock broke apart).

An object may be treated as an extent (nelima o rumic buma meynú the box is 2 hands wide) or as a point (rónuc o nelima o dmuru bundeš meynú the box is 20 hands from the wall). Using the TIME IS SPACE metaphor system, events can be treated the same way: he lived for 70 years / he lived in the Age of Petty Kings.

An instance verb conceptualizes the action as occurring at a point in time:

But if you zoom in close enough to something pointlike, it becomes a perceptible extent— that is, a process:

Given an instance verb, we can zoom in to force a process reading:

With a process verb, we can zoom out till the process looks like a point again.

Sinde imišeji. He began to speak

Cu sindej na dzus pej. He’s just finished speaking

Sinde rap He keeps speaking.

Aycaur rap He’s always reading.

A moving perspective may be implied even if nothing is physically moving, e.g. in the following examples by the highlighted time expressions:

Rina neyo giesnar dzunyo jima.

river across castle afterwards hill

Across the river is a castle and then a hill.Rina rano kiras daumaur ga pejom.

river along villages times ADV stand-3p

There are villages now and then along the river.

kaym / kaynes buy / sellSimilarly, the choice of impersonal tas ‘us’ or ros ‘people’ depends on whether one pictures oneself inside or outside the group referred to:

rae / xame go / come

emurac / jireac marry a man / marry a woman

maypayvú / kissú parents / children

Bicikes ray dopalurač izom / ayzuc.

Academy in arrogant be-1p / be-3p

In the Academy we / people are rude.

Color terms vary widely between languages in number and boundaries, but the focal or prototypical colors are nearly identical: Xurnese širp green has the same focal color as Verdurian verde, Kebreni kyr, Old Skourene -arṭ, Uytainese hur, Trêng šuda. However, it’s not the same as English focal green, because the eyes of Almean humans are not quite the same; ‘Almean green’ is slightly bluer than our green.

Languages may provide explicit ways of indicating how far a referent differs from the prototype:

The existence of basic categories answers Quine’s objection to ostension—e.g. that pointing to a rabbit cannot be used to define ‘rabbit’, since the speaker might be referring to rabbit noses, the act of running, or a miscellaneous collection of rabbit parts. Linguists studying language acquisition, such as Eve Clark, report that children apply some simple rules:

Of course, these categories are basic to humans. This is clearest with human-oriented words like sis chair, which are defined not so much by shape as by interaction with the body. But even the taxonomic categories are not ‘natural kinds’ pre-existing in the world. They are natural to human minds interacting with the world with human bodies.

Other slang terms are abbreviations or diminutives, or wordplay, or are borrowed from other languages:

Xurnese standard

meaningcolloquial

meaningaga baby newbie ejize poke have sex naušis suck drink heavily nulač ill messed up pidaup a drink alcoholic drink pucišu major gourmand tetiy chop off shut up weli old ones parents yas cheek mouth

As in English, there’s a continuum from colloquial to slang to obscene registers. Slang goes hand in hand with regionalism; if you’re departing from the standard, you’ll probably head in the direction of your native speech.

term gloss source bici Academy abbreviation of Bicikes endevu protegé abbreviation of endevugaup šara crap abbreviation of šaragú kurešiy girl, chick ‘trouser person’ nauziš eat Ṭeôši pečya boss Ṭeôši šuzir fabulous Ṭeôši galnu crazy Tžuro joir pal Tžuro nastuja whore Tžuro ingu booze Kebreni nabro captain Kebreni jusam stuff Verdurian

Words do not appear in their Axunašin forms. Xurnese script is partly logographic (with the consequence that logographs don’t reflect pronunciation at all) and partly syllabic; but the syllabary is highly archaizing. For instance, the script still distinguishes Axunašin e/ei and ou/o; in fact, this is the only way the script distinguishes c and t, or dz and d. Initial consonant clusters are still written with the ancient vowel; e.g. mnaur ‘wear’ is written minaur, while Mnau the peninsula is written Menau. Axunašin endings would be unusable in Xurnese. Thus the Axunašin spelling is generally unavailable, unusable morphologically, or not distinctive anyway.

Instead, Axunašin words are borrowed by meaning. Only if there is no clear cognate is the word borrowed by sound.

The worst offenders are books on magic and Mešaism, which use words in their classical meanings (e.g. mneušis ‘invite’ is used in its ancient sense of ‘gesture’, mes ‘woman’ in the sense of ‘mistress’, xu ‘bad’ as ‘evil’).

The earliest Endajué writings relate to a different stratum, the Old Xurnese of 1700 years ago. As these works are very familiar, the senses involve remain current, but may be restricted to religious contexts. For instance, dzaus ‘teach’ is still common, but for secular senses is replaced by zende, while xaleza ‘elite warrior’, like our ‘knight’, retains emotional resonance but is outmoded as a military term (cf. newe ‘general’, juysu ‘commander’).

Modern scientific terminology (including manufacturing and navigation) contains its share of Axunašin, but also heavily borrows from Tžuro (e.g. jeku ‘steel’), Kebreni (šenu ‘clock’), and Verdurian (e.g. resteko ‘telescope’).

Through the early Xurnese period the hours were sunrise to sunset, so they varied by the season. Astronomers and navigators preferred amuri (that is, equal-length) hours, and once good mechanical clocks existed (around the time of the Revaudo revolution), this became general.

Xurnese Axunašin time hours xora botino dawn 6 to 8 a.m. yeucino yoxino mid morning 8 to 10 a.m. šircino širtino late morning 10 a.m. to noon taucino tausetino early afternoon noon to 2 p.m. picino pinatino mid afternoon 2 to 4 p.m. baycino bantino late afternoon 4 to 6 p.m.

In ancient times the nighttime was not given hours; but kip ‘dusk’ was used for the first hours after sunset. By the Xurnese period the hour names were simply extended into the night, with the prefix nosuš ‘nocturnal’: e.g. nosuš yeucino mid-evening (8 to 10 p.m.). Now that lighting is better and evening events are common, the latter period is also known as kip dzus ‘after dusk’.

Xurnese prefers its more specific names for time periods, and has no terms for ‘morning’ and ‘afternoon’. However, two adjoining periods can be combined: yeušircino ‘2nd/3rd hours’ = 8 to 12 a.m., širtaucino ‘3rd/4th hours’ = 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., etc.

Few people recognize that the prefixes derive from the Wede:i numbers; their meanings are taken to be the times of the day, and can be used as abbreviations: e.g. taukéjuc ‘a meal eaten at noon’; baykejúcis ‘late afternoon snack’; pidéynduc ‘2:00 appointment’.

Hours are typically divided by fractions, e.g. taucino teč ‘taucino plus half a šaruc’ = 3 p.m. Astronomers divided the šarus into 100 deymisi ‘instants’, and clocks now have a déymis hand, so that city dwellers, at least, deal with times like picino li yumudeš deymisi ‘5 hours 80 instants’ = 4:36 p.m.

The hours can be used both to refer to the period of time, and to the instant that begins them. Thus taucino has increasingly displaced eudis ‘noon’, which however retains its metaphorical meanings such as ‘zenith, high point’.

(For simplicity’s sake I’ve treated the šaraup as exactly two hours; in fact it’s slightly longer, as the Almean day is about 24 1/2 hours long.)

day gloss indis first day pudis second day dzindis third day nimala market peykaudis fifth day seyčaudis sixth day šizaudis seventh day yusaudis eighth day tagri final (day)

Days are numbered within the season: e.g. dzayndešpayk kuludo ‘the 35th day of fall’. Each season has 82 days. (Because this doesn’t match our year, exact Earth equivalents can’t be given.)

season gloss Verdurian equivalent rough Earth equivalent eči summer 16 cuéndimar - 15 recoltë June / July / August kuludo fall 16 recoltë - 15 išire Sept / Oct / Nov raujic winter 16 išire - 15 bešana Dec / Jan / Feb sumbrey spring 16 bešana - 15 cuéndimar March / April / May

The numbering aligns with the calendar, not the movements of the planet; thus am eči ‘the 1st day of summer’ is New Year’s and precedes the solstice.

In ancient times the Axunemi emperors inserted a nonce leap day whenever the year wandered too far out of sync with the planet. This became chaotic in the Age of Petty Kings as a different schedule was followed in each kingdom. The Xurnese finally regularized the system by adding a leap day (an extra day in sumbrey) every five years.

Bezu ma-Veon Bezu son of BeonPatronymics appear after the name, a practice which dates back to Axunašin, where heavy modifiers could migrate after their head. The use of locatives is more recent and follows the standard modifier-head order.

Joraumiri Enirc Enirc of Joraumi

Jamimbri Xayu ne-Rilirc Xayu daughter of Rilirc of Jamim Colony

Naturally it wouldn’t do to have most of Inex surnamed Inegri; the locative may refer to the provenance of the parents or more remote ancestors.

In the cities, people are most commonly referred to using titles:

Aulic joraumirc Councillor AulicEveryone has a title—if nothing else róses ‘citizen’. If foreigners have a rank (e.g. dalonaysu ‘ambassador’, imimex ‘ship captain’) it’s used, otherwise they are neyosu ‘alien’, or empojaup if they are legal residents of Xurno. Other Thinking Kinds may be referred to using their species: Sulbelid gedzaysu ‘elcar Thulbelidd’.

Deru xairc Student Deru

Enirc jivirc Walker Enirc

Weneš bicikesiy Academician Weneš

Gašnue dzusey bicikesiy Master Academician Gašnue

Kaleon empojaup neyosu Permitted Alien Caleon

Raujic reyxu Lieutenant Raujic

Yute saus Cousin Yute

Within a family, kinship terms are preferred; elsewhere, religious, artistic, or military ranks. Titles of nobility are only used for foreigners (or in backwards areas like Bozan).

The title follows the name; this is not an exception to the rule that the head appears last in an NP, since the title is the head, as can be seen by the fact that on second reference the name, not the title, is dropped. That is, if you’re talking to Enirc you normally call him by his title, jivirc, not by his name. If you are talking to multiple jivircú, you use the full name and title.

Only close friends, lovers, and siblings use the name alone.

As Endajué disbelieves in gods and yet considers the Dance divine, you can insult someone both by calling them godless (nanač) or god-following (dzunan, nansu).

expletive gloss English equivalent tegendi pathless damned (very strong) nanač ungodly damned (less strong) tebengi (taboo-def.) darned, frigging berirri deluded godforsaken bodugri lame ignorant, irreligious end’ eš against path dammit! cuš eš against dance dammit! dzunan pagan infidel, bastard šwečirc striver fool nansu god-man pagan, priest-ridden i puide spit me damn me!

The Mešaic formula for making an oath was (god) leš sindú I speak before (a god), and this was transferred to the Path (ende), the dance (cuš), the Greater and Lesser Principles (šwerayjú), or the masters (dzuséy). Oaths are heightened with a little sacrilege; the difference between cuš leš and cus eš is similar to that between “dammit!” and “damn me!”

Similarly, to ask (say) Meša to curse someone, you said Meša toš puide! May Meša reject him! Endajué entities, abstract as they are, can be asked to do the cursing. (This construction is so ancient that it’s one of the few surviving uses of the subjunctive as an imperative.) As puide is now largely used literally (‘may it spit’), similar terms may be substituted, especially šauvide ‘may it vomit’ and mišide ‘may it piss’.

Bodily functions are a rich source of despectives, especially pija ‘shit’ and mišu ‘piss’ and their derivatives.