|

| ||||||

Barakhinei

Barakhinei  Introduction

*

History

Dialects

Gender differences

Introduction

*

History

Dialects

Gender differences

Phonology

*

Dialectal variations

Stress accent

Orthography

Phonology

*

Dialectal variations

Stress accent

Orthography

Sound changes from Caďinor

Sound changes from Caďinor

Morphology

*

Nominal declension

Adjectives

Pronouns

Numbers

Conjugation

Morphology

*

Nominal declension

Adjectives

Pronouns

Numbers

Conjugation

Derivational morphology

*

Nominalizers

Adjectivizers

Verbalizers

Derivational morphology

*

Nominalizers

Adjectivizers

Verbalizers

Syntax

*

Constituent order

Noun phrases

Articles

Case usage

2p pronouns

The subjunctive

Prepositions

Phatic particles

Negation

Questions

Clauses

Syntax

*

Constituent order

Noun phrases

Articles

Case usage

2p pronouns

The subjunctive

Prepositions

Phatic particles

Negation

Questions

Clauses

References

*

Conventional expressions

Calendar

Names

References

*

Conventional expressions

Calendar

Names

Example

Example

Lexicon

Lexicon

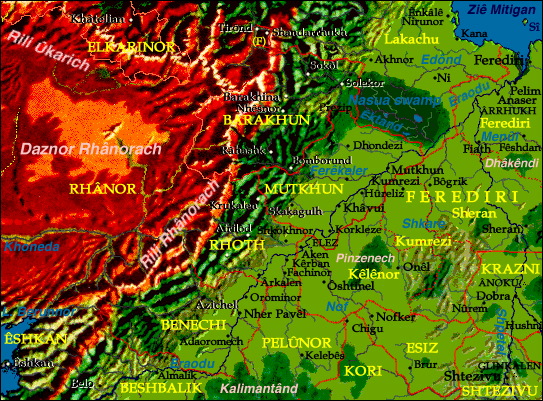

The map is labelled entirely in Barakhinei. Ferediri is Barakhinei for "Verduria". For Verdurian names see the Eretald map.

A feudal state that had no truck with modernity, Barakhún, unlike Verduria, perceived no need to write its few documents in the vernacular; it produced no literature except official annals and religious exhortations; and trade beyond the shop level was carried out by foreigners, mostly Verdurians. Ironically-- for the Barakhinei are a warlike, male-dominant culture-- it was women who first developed Barakhinei as a written language. Noblewomen were taught to read Caďinor, but were rarely given enough instruction to write fluently in it; at the same time, armies of servants made them the only leisured class in the country. Our first texts (of more than a line or two) are letters from one noblewoman to another.

By the reign of Lombekh (d. 3110), father of Ambekh the Great, women such as Ilitira, Kondên and Tizati were writing romances, poems, and essays in Barakhinei. Within a century they were joined by men; and when the Union of Eleďi and Arašei was accepted in Barakhún (in 3225, more than two centuries after its promulgation in Avéla), Eleďe clerics began preaching in the vernacular, and we begin to find sermons, lives of saints, and devotional manuals in Barakhinei.

It was not till the 3300s that official documents were written in Barakhinei in Barakhún, Hroth, and Mútkün. (Rhânor is a special case; it is too primitive to have official documents; but women and clerics are likely to know how to read.)

The usual spellings of all three of these countries in Almean studies differ from the transliteration used in this chapter, under which they would be Barakhun, Rhoth, and Mutkhun. The accents simply indicate the placement of the stress, which is not indicated in the Barakhinei alphabet; the other variations reflect local dialect pronunciations.

Given this history, it should not be surprising that earlier forms of the language are available only accidently, or via internal reconstruction; and that very few serious scholarly resources exist. The best Barakhinei grammar is that of the University of Verduria (Aluatas Šriftanáei Barahineë); the best native work is the Fisnava Rhuo Barakhinei by Ekuntâl of Sûlekeros.

[f] and [v] are allophones, [v] appearing only intervocalically; but they are spelled with two different symbols, and Verdurian loan-words retain an initial V, which some attempt to pronounce correctly.

Rather than a random collection of ten vowels, consider the vowel system as consisting of two series of five vowels each, the tense vowels i e a o u and a lax series î ê â ô û. Alternations between tense and lax vowels are common in Barakhinei morphology.

Final î, and post-stress û, are pronounced [e]. Other vocalic reductions of unstressed syllables are characteristic of Southern dialect and of male speech.

In addition, ô tends to lower to [a] (pushing a to [a]); thus Verdurian borrowings like iladil, ďarim from ilôdil, dhorind.

Southern dialect is known for pronouncing rh as an unvoiced aspirated r-- thus the spelling Hroth, spelled Rhoth in the transliteration used here. (This spelling also hints at the southern spelling rc for northern rh.)

It's also known for the deaffrication of ch to palatal c, the fricativization of intervocalic velar stops (k --> kh, g to gh),

Stress is not indicated orthographically.

The alphabet inherited from Caďinor was:

For a period after the fall of the empire, writing was not used in the mountain lands, except inscribed on stone, or carved into wood. The characters were adapted to be easily produced using these methods:

When paper and ink were once again available, the letters were adapted once more to the medium, and a distinctive decorated mountain hand emerged.

(The characters shown are based on contemporary Barakhinan scribal handwriting. The letterforms are the same in the other Barakhinei lands, though the details differ. ) The names for the letters are

u a ô ê i êk

pe kê bê gê dakh

sa thê zash tê dhakh

ra khôth le

mê fa nhê fek hê

The letters marked <k c> have the values /q k/ and are used as such when writing Caďinor or Verdurian. Only the second character, <c>, is used for the /k/ of Barakhinei.

Digraphs are used for the new sounds that have developed since Caďinor times. The second character in ch nh lh (ik) derives from a small i; the second character in sh and the middle stroke in rh derive from h and indicate aspiration; both are called hêkek. (rh is considered a digraph, and indeed in Hroth it is written rc.)

The new vowels û â ô ê î are indicated with a diacritic (a bazêl 'lowering'), equivalent to the Verdurian mole, and likewise derived from a miniature u.

The usual Roman transliteration of Barakhinei preserves one of the chief features of the alphabet, the use of digraphs. Admittedly, however, the transcription is not entirely accurate-- we should write dh th kh as single characers, as in the preferred transliteration of Verdurian; and perhaps we should write kj nj lj rather than ch nh lh. On the other hand, the transliteration emphasizes the difference from Verdurian, reminding us that (say) čun and chund, hum and khum, zon and zôn look quite different to Almeans:  .

.

The ö ü of Central dialect are written o u (i.e. without a diacritic), or sometimes oe ui.

The numbers have been adapted from those of Verdurian (except for 7, formed from 6 by analogy).

There are no capital letters, and only two punctuation marks, one used for a pause and one to mark the end of a sentence. There is no exclamation mark or question mark. Words are separated by spaces, but pronouns and particles are not always separated from adjoining words.

| o → u /_[r,m,n]# | anor → anur → anu |

| a → o /_rV | aracnis → orakni |

| s → z /V_V | esistes → ezishtê |

| f → v /V_V | oforis → ovori |

| th → dh /V_V | pethuera → pedher |

| n → ñ /#_e | nebri → nhêbor |

| n → ñ /_iV | nies → nhê |

| ng → ñ /_F | vange → fanh |

| lg → | fulgo → fulh |

| [+nasal] → 0 /r_ | cernan → kera, dormir → dôri |

| s → 0 /o_# | calenos → kalen |

| i → ch /V_V | Alameia → Alamech |

| [+vel] → ch /V_F, #_i | lereges → lerchê, cista → chisht |

| t → ch /_u | tuca → chuk |

| ti → ch /#_V | tiamora → chamor |

| a → ô /_l[+stop] | khaltes → khôtê |

| e → û /_l[+stop] | cthelt → kthût |

| i → 0 /e_ | leilen → lelê |

| ae, ai → â | raedhos → râdh, raikh → râkh |

| eu, eo → û | seo → sû, leus → lû |

| e → ê /_C#, _CC | macres → makrê, mergen → mêrgê |

| o → ô /_C#, _CC | estol → êshtôl, bursoncos → bursônk |

| u → i /_CF | lupekh → lipêkh, faucir → faichi |

| n,m,s → 0 /_# | dotis → doti, esan → eza |

| r,c,t → 0 /CV_# | failir → fâli; but aure → air |

| V → 0 /_# | onella → onêl, nare → nor, miscu → mishk |

| C1 → 0 /_C, C = C1 | pinna → pin |

| li → | Iliages → Ilhachê |

| r → or /C_# | kapro → kapr → kapor |

| i → e /_l# | ladrilo → ladril → ladrel |

| s → z /n_ | nagensa → nachênz |

| au → ao | Endauron → Êndaoru |

| u → 0 /o_ | bounos → bon |

| ps → shp | opser → ôshpê |

| p → 0 /_t | saeptos → sât |

| s → sh /_S | suest → sêsht, scamea → shkame |

| c → sh /_S | mactana → mashtan, ctanen → shtanê |

| k[+liquid] → rh | kredec → rhedê |

| khr → rh | khruis → rhî |

| i → h /#_V | iagen → hachê |

| u → f /#_V | ueronos → feron |

| ui → î | khruis → rhî |

| iu → î | siuro → sîr |

| l → 0 /_[+stop] | khaltes → khôtê |

| l → 0 /XCu_# | kethul → kedhu |

| l → r /_r | gulres → gurrê |

| k, c → k /_ | cassis → kasi, kattis → kati |

| u → 0 /_V | latuan → lacha |

| v → f /#_, _# | volir → foli, kerovos → kerof |

| h → 0 /V_V | mihires → miirê |

| g → k /_# | minga → ming → mink |

| b → p /_# | gribos → grip |

| gn → ñ /_# | cugna → kunh |

| s → 0 /_ch | plestura → plêschura → plêchur |

| s → sû /_C# | ereslos → erêsl → erêsûl |

| s → sh /C_# | dorsos → dôrs → dôrsh |

| k → 0 /_ch# | noctu → nôkch → nôch |

| s → h /_m | tekresmes → têrhêhmê |

Masculine hints s.nom eli lônd âshta s.acc eli lônd âsht always = root s.dat elia lônda âshta always -a s.gen elio lôndo âshto always -o pl.nom eliri lôndi âshtâ eli differs from lônd only in pl. root pl.acc/dat elirî lôndî âshtî always -î pl.gen elirich lôndich âshtach = pl.nom laxed + ch Neuter s.nom kal shkor nôshti manu shpâ in s., shkor follows kal s.acc kalu shkoru nôshti man shpâ acc = dat exc. for manu s.dat kalu shkoru nôshti manu shpâ s.gen kalo shkoro nôshtio mano shpach all end in -o, like masc. pl.nom kalo shkoru nôkchu mani shpao in pl., shkor follows nôshti pl.acc/dat kaloi shkorî nôkchî manî shpaoi in oblique forms, pl.gen kaloch shkorich nôkchich manich shpaoch kal is odd man out Feminine s.nom chir nor medhi elorê kabrâ s.acc chira nore medhi elore kabra s.dat chirê norê medhiê elorê kabrê always -ê s.gen chirach norech medhich elorech kabrach = acc. + ch pl.nom chirâ norê medhiê eloriê kabrachâ pl.acc/dat chirêi norêi medhia eloria kabracha pl.gen chirech norech medhiech eloriech kabrachech always -ech

The most important factor in the historical development of the declensions in Barakhinei was the loss of the final consonant or vowel in almost every case form. Subsequent analogical change has reversed some mergers and brought some of the declensions closer together.

To decline a noun with confidence, you need to know its gender and its plural. The former is always indicated in the lexicon, and the latter when necessary.

(Knowing the Caďinor etymon almost always does the trick as well. However, beware of a few words (e.g. piabor 'grandfather') which have shifted to a more 'logical' gender. The Verdurian cognate will identify feminine nouns, but won't distinguish masculine and neuter.)

The citation form for adjectives is the masculine s.nom.

I Declension 'south' 'north' m. n. f. m. n. f. s.nom âr âr âr na na na s.acc âr âru âra na nanu nana s.dat âra âru ârê nana nanu nanê s.gen âro âro ârach nano nano nanach pl.nom âri âro ârâ nani nano nanâ pl.acc/dat ârî ârî ârêi nanî nanî nanêi pl.gen ârich ârich ârech nanich nanich nanech II Declension III Declension 'calm' 'round' m. n. f. m. n. f. s.nom gelê gele gelê ori ori ori s.acc gelê gelê gele or ori ori s.dat gela gelê gelê ori ori oriê s.gen gelo gelo gelech orio orio orich pl.nom gelê gele gelê ori oru oriê pl.acc/dat gelî gelê gelêi orî orî oria pl.gen gelêch gelech gelech orich orich oriech

For some I adjectives, such as na, the final consonant is lost in the s. nom. and the m. s. acc. In the lexicon this root is cited as na (n), indicating the consonant to be restored.

There are two adjectives in -â (mudrâ, shkrâ). These follow the patterns for nouns in -â; the masculine forms are identical to the neuters.

Adverbs are expressed by conjoining the feminine s. nom. form of the adjective to meli 'way': iziêth meli 'importantly'; lebê → lebe meli 'newly'; rochi meli 'crazily'.

The third person singular pronouns are the same as the demonstrative pronouns, and do not vary by sex: ât can be 'this one, he, she, it (over here)'; tot can be 'that one, he, she, it (over there)'. The two pronouns can be used as proximative and obviative pronouns, referring unambiguously to two separate referents:

nom. gen. acc. dat. I sû (eri) sêth sû thou lê (leri) êk lê this one ât âti âtô âta that one tot toti tô tota we ta (tandê) tâ tao you mukh (mundê) mî mî they kâ (kandê) kâ kâ refl. zei zêth zeu refl. pl. zai zaa zau who/what kêt kêti kêtô kêta

Ât tota fetâ chî tot shkrif chî ât laodâ oloka mônê.In isolated regions in Barakhún and Mútkün, the third person singular pronoun, chu, derives from Caďinor tu 'he/she' rather than aettos/totos 'this/that one'.

He1 said to him2 that he2 knew he1 would get sick

Eri, leri, tandê, mundê, and kandê are regular adjectives, and must be declined as such: eriê nagâ 'my feet', tando firakho 'of our enemy'.

Reflexive pronouns are used (much as in Verdurian) both for true reflexive uses (zêth shkrivê 'to know oneself') and to make transitive verbs intransitive (zêth eterê 'to run by itself').

which kê this âl that il who, what kêt this one ât that one tot where kedi here âsht there kêsht when ked now âl khor then il dêna every, all shkei some nhê none sî everyone shpiê someone thizi no one nikt everywhere shkei nor somewhere nhê nor nowhere sî nor always shkei dêna sometimes nhê dêna never sî dêna how kênz how much shkol why poche

âl, il, shkei, thizi are declined as regular adjectives; nhê, kê and sî are invariable.

No animate/inanimate distinction is made with these pronouns: kêt means both 'who' and 'what'; thizi means both 'someone' and 'something'.

The locative pronouns have dative forms kediê, âshta, kêshta, used only by men.

digit x10 ordinal fraction 1 a dêsht perê perê 2 dhu tedêsht torê mechî 3 di medêsht merê dinga 4 pao chedêsht chêtnê barga 5 panth pandêsht pantê pantê thur 6 sêsht sêdêsht sêshtê ... 7 khâp hedêsht khâpê 8 hoch hodêsht hôkri 9 nhêbor nhêdêsht nhêbri 10 dêsht sekath dêshti

Numbers up to four are declined as regular adjectives (dhunâ nagâ 'two feet', paorich boboch 'of four fools'); higher numbers, including combinations, are invariable (sêsht genî 'to six clans'). The ordinal numbers are also regular adjectives.

Numbers from 11 to 19 are formed by conjoining dêsht plus the digit name, which receives the accent: dêshta, dêshtdhu, etc. The only spelling changes are 16 dêsêsht and 18 dêshtoch. Other two-digit combinations, however, are formed as conjoined phrases: 21 tedêsht êr a; 54 pandêsht e pao; 78 hedêsht e hoch.

Higher numbers are fairly straightforward: 3487 = di mel pao sekath hodêsht e khâp.

(There are enough mergers that the verb form alone does not determine person/number. In Rhânor and in southern Hroth, pronouns are generally included for all persons; elsewhere, only for second person.)

elirê

liverikha

look atlelê

seebêshti

movehabê

wearHints I.sg. elira rikhâ lelâ bêch hap II.sg. elirû rikhê lelê bêshtû habû either -û or -ê III.sg. elirê rikhê lelê bêshti habê almost always -ê I.pl. eliru rikha lela bêkchu habu either -u or -a II.pl. eliru rikhu lelu bêkchu habu always -u III.pl. elirôn rikhôn lelên bêshtîn habun always -Vn grochê

millfoka

invokenochê

squeezefaichi

leaveklachê

beatI.sg. groga fokâ nogâ faok klak II.sg. grochû fochê nochê faochû klachû III.sg. grochê fochê nochê faichi klachê I.pl. grogu foka nocha faoku klagu II.pl. grogu foku nochu faoku klagu III.pl. grogôn fokôn nochên faichîn klagun

Sound change has affected Caďinor verbal roots ending in c or g quirkily enough that it's worth giving a full set of examples, with phonetic changes highlighted.

Bêshti shows a more restricted sound change: -sht- changes to -kch- before -u (not -û).

A Caďinor -u- is fronted before a front vowel; this accounts for the alternation faich/faok. This always affects the III.sg; in the rikha conjugation it affects the IIsg as well (chura → chirê); in lelê conjugation, it affects all but the I.sg. (In Central dialect it remains rounded: 'leave' is faüchi.)

In the bêshti and habê conjugations only, a final -d, -t, or -p in the verbal root generally changes to -dh, -th, or -v/f in the I.sg. and plural forms: sidê 'offer' → sidh, sidû, sidê, sidhu, sidhu, sidhun.

Finally, note the devoicing in hap, klak.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê I.sg. eliri rikhi leli bêshti habi always -i II.sg. elirî rikhi leli bêshtê habê III.sg. elir rikhâ lelâ bêshtâ hap -â or nothing I.pl. elirê rikhu lelu bêshtê habê II.pl. elirê rikhê lelê bêshtê habê always -ê III.pl. elirîn rikhîn lelîn bêshtên habên always -(ê,î)n grochê foka nochê faichi klachê I.sg. grochi fochi nochi faichi klachi II.sg. grochî fochi nochi faichê klachê III.sg. grok fokâ nogâ faokâ klach I.pl. grogê foku nogu faichê klachê II.pl. grogê fokê nogê faichê klachê III.pl. grochîn fochîn nochîn faichên klachên

In Proto-Eastern the past tense was formed by a change in stem vowel; this can still be seen in Barakhinei, in the substitution of front vowels for the back vowels in the present tense.

Again, alternations of Caďinor roots in -c, -g are given; and note the devoicing in hap and grok.

The -u- fronting (faich/faok) affects almost all forms in the past tense, sparing only the endings -â, -u and the III.sg for elirê verbs.

The -sht- → -kch change we met with bêshti in the present tense here affects only forms ending in -u, while -sht → -ch in the III.sg for the first -ê verbs: têshtê → IIIsg têch.

In the elirê conjugation only, a root ending in -d, -t, -p has a III.sg. ending in -dh, -th, or -f: rhedê 'believe' → rhedh 'he believed'. Note that this affects a different conjugation than the corresponding change in the present.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê I.sg. elirri rikhri lelri bêshtri habri II.sg. elirrî rikhri lelri bêshtrê habrê III.sg. elirêr rikhrâ lelrâ bêshtrâ habêr I.pl. elirrê rikhru lelru bêshtrê habrê II.pl. elirrê rikhrê lelrê bêshtrê habrê III.pl. elirrîn rikhrîn lelrîn bêshtrên habrên

The past anterior tense (used for actions taking place before the time referred to by the past tense) is formed by adding -r- to the verb root, followed by the past tense endings. The exception is the III.sg. endings for elirê and klachê verbs: null in the past tense, -êr in the past anterior.

The past anterior endings are always stressed.

No root alternations are found in this tense.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê I.sg. elirta rikhmâ lelmâ bêshtech habech II.sg. elirtê rikhmê lelmê bêshtech habech III.sg. elirtê rikhmê lelmê bêshti habti I.pl. elirtu rikhma lelma bêshchu habchu II.pl. elirtu rikhmu lelmu bêshchu habchu III.pl. elirtôn rikhmôn lelmên bêshtîn habtîn

The subjunctive, derived from the Caďinor remote static present, is formed by adding -t- or -m- to the verb root, then the subjunctive tense endings. For all but the highlighted forms, these are the same as the present tense endings. Also note that -tu changes to -chu in the I.pl and II.pl for the bêshti and habê conjugations only.

In speech, the endings devoice the ending of the verbal root (habchu → hapchu), but this is not reflected in writing.

Some verbs have a distinct subjunctive root, noted in the lexicon. E.g. laoda 'go' → subj. I.sg. lodâ, not *laodmâ.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê I.sg. elirka rikhnâ lelnâ bêshtir habir II.sg. elirchê rikhnê lelnê bêshtir habir III.sg. elirchê rikhnê lelnê bêshtri habri I.pl. elirku rikhna lelna bêshtru habru II.pl. elirku rikhnu lelnu bêshtru habru III.pl. elirkôn rikhnôn lelnên bêshtrîn habrîn

The past subjunctive is formed like the present subjunctive, but using a different infix: -k/ch- for the elirê conjugation, -n- for the rikha and lelê conjugations, -r- for the others. In the latter, note the special ending in the I.sg and II.sg.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê II.sg. elir rikh lel bêch hap II.pl. elirêl rikhel lelel bêkchu habu III.sg. elira rikha lela bêkcha haba III.pl. eliran rikhan lelan bêkchan haban

The II.sg. imperative is usually just the verb root, with some irregularities. The bêshti and habê forms are the same as the present tense I.sg. The rikha forms show the c,g → ch softening: foka → foch; they and the lelê forms also turn a -u- into an -i-: chura → chir. Final -b, -g are devoiced in all conjugations.

The II.pl. imperative in the bêshti and habê forms are the same as the present tense forms. For elirê verbs, it's the same as the present III.sg. plus -l; for rikha and lelê verbs it's the same as the past I.sg. plus -l.

The III.sg. forms all show the root alteration u →i (chura → chira). Final -d, -t, -p in the root become -dh, -th, -v. The III.pl. forms simply add an -n onto this.

Pronouns are never used with the imperative.

elirê rikha lelê bêshti habê past elirêl rikhu lelu bêkchu klachêl present eliril rikhê lelê bêshti klachê

Participles are regular adjectives; those ending in -u have an oblique root -ul-.

Root alternations can be deduced from the first vowel of the ending: e.g. foka → past foku, present fochê.

Participles can be used (appropriately declined) wherever an adjective can be used: dôriê honiê 'sleeping women'; kekulo pono 'of the killed warrior'; raolu kâbol 'cooked onion'.

The present participle gives a progressive or continual meaning; the past participle gives a perfective (but not a passive) meaning (equivalent to the Verdurian ya).

Rikhâ ila dezi. I see the bridge.The future tense is formed with laoda 'go' + the infinitive: laodâ proza 'I am going to walk, I will walk'.Sâ rikhê ila dezi.

I am looking at the bridge; I often look at the bridge.Sâ rikhu ila dezi.

I have looked at the bridge; I just looked at the bridge.Lê klachê il rhez. You beat the dog.

Lê sê klachêl il rhez.

You were beating the dog; you always beat your dog.Lê sê klachê il rhez.

You have beaten your dog; you've finished beating your dog.

eza 'to be' pres. past. past ant. subj pres subj past I.sg. sâ fuch firi êshta êshka II.sg. sê fuch firi êshtê êshkê III.sg. ê fâ furâ êshtê êshkê I.pl. eza fu furu êshta êshka II.pl. ezu fuê furê êshtu êshku III.pl. sôn fûn firiôn êshtôn êshkôn epeza

'can'foli

'want'lhibê

'love'kedhê

'bear'present past present present present past I.sg. ûzâ ûzi ful lhua kedhâ kedhi II.sg. ûzê ûzi ful lhû kedhê kedhi III.sg. epê epâ fut lhu kedhu kiâ I.pl. epeza ûzu folu lhubu kedha kedhu II.pl. epezu ûzê folu lhubu kedhu kedhê III.pl. ûzôn ûzîn folîn lôn kên kedhîn nhê

'be born'shkrivê

'know'shtanê

'come'fâli

'need'hizi

'provide'oi

'hear'present present present present present present I.sg. nhe shkriva shtâ fâl huz oh II.sg. ni shkri shtê fêl hu fi III.sg. ni shkri shtê fêl hut fit I.pl. nheza shkrivu shtana fâlu hizu ou II.pl. nhezu shkrivu shtanu fâlu hizu ou III.pl. nhên shkrivôn shtôn fâlîn hizîn oîn

In addition, twenty or so verbs (and their derivatives) have an irregular subjunctive stem, indicated in the dictionary. For instance, laoda 'go' has the subjunctive stem lod-. So instead of forming the present subjunctive *laodmâ, *laodmê... it's lodâ, lodê, lodê, loda, lodu, lodôn; and the past subjunctive is not *laodnâ... but lodi, lodi, lodâ, lodu, lodê, lodîn.

Ili ekuni dezdîn lebê elorî.With case marked for most words and subject agreement on the verb, word order is fairly free. There is a tendency to move the topic to the beginning of the sentence; this is done where English would passivize:

The princes selected a new king.

Honê sîkeram rizundâ âla foela.

A shameless woman wrote this letter.

Il lebê elorî dezdîn ili ekuni.

The new king was selected by the princes.

Âla foela rizundâ honê sîkeram.

This letter was written by a shameless woman.

Pronominal objects are normally placed before a conjugated verb, but cliticized after an infinitive.

Il shkokh shkri purho zei shkenhêi.A direct object pronoun precedes an indirect one:

The governor truly knows his chickens.Il shkokh kâ shkri purho.

The governer truly knows them.Ât fut shkrivêkâ.

He wants to know them.Lê laodâ fetê pomaire.

I'll tell you a story.

Âto tota di. I gave it to him/her.

Tot sû di! Give me that!

âl bop that fool

kaokh feredê a green lizard

kôn eri my money

têrsê il chuz all that shit

il kân glini felachach eri the long pen of my aunt

dhuni poni thainê two left-handed warriors

il ebdûn khip dezi the troll under the bridge

As the demonstratives have not completed their transition to articles, it is not surprising that certain English article usages do not occur in Barakhinei. In general il can be used as an article only when the referent has been explicitly mentioned ('The king is here. I hate the [il] king.') or, in speech, when it is present. A reference by implication won't do. Thus we can say 'I visited the palace. The king was there.' In Barakhinei one must say Elorî fâ kêsht, literally, 'King was there.'

Il should not be used as an article in genitive expressions: il midor chinach 'the mother of the bride' (not *ilach chinach).

Il elorî badhâ ila elore.Nominal indirect objects are expressed by men using the dative; by women using the preposition a followed by the accusative:

The king hit the queen.Il elorê badhâ zei giru.

The queen hit the horse.Il gir badhâ ila kôshka.

The horse hit the cat.

Di il shkuchua âdhechua eri.Destinations are expressed the same way:

I gave the pig to my church. [male]Di il shkuchua a âdhechu er.

[female]

Il klâtandu laodê mashtanê.Prepositions govern the accusative, though some male writers, following Caďinorian and Verdurian usage, use the dative for locative expressions (as opposed to those expressing movement).

The priest is going to the city. [male]Il klâtandu laodê a mashtana.

[female]

Il salhê naku laodê a kelere.

The dirty man is heading for the river.Il tren letâ tra kôrke.

The turtle flew across the canyon.Dom eri ê tra kelere.

My house is across the river.Dom eri ê tra kelerê.

[same, for male pedants]

The genitive is used for possessives: hôrt elorîo 'the king's toe'. Note that declinable possessive adjectives, not pronominal genitives, are used for most pronouns: sinor eri 'my mother-in-law'; genitive sinorach orich; plural sinorâ ori; pl. acc. sinorêi orî, etc.

In expressions involving a superior in rank ("the boy's master"), the inferior does not appear in the genitive, but in the dative (in male speech, or using 3s pronouns) or a + accusative (in female speech):

pidi ekuna the prince's father [male speech]

pidi a ekun [female speech]

pidi âta his father (he = the prince)medh ekuno the prince's son

medh âti his son

Il shkokh ful nhê fin?Children (up to the nakî or manhood ceremony) use lê for everyone. So do women: it's considered cute in women (and very offensive in men) to address everyone in this 'childlike' way.

Would you (lit., the governor) like some wine?Il klâtandu sîk amêti ibor?

You (the priest) didn't bring the book?Moru duzorech tekê dorovê?

Your (the mayoress's) husband is fine?

Note that lê or a title is almost always explicitly inserted, except with imperatives, since the verb endings alone do not always distinguish second from first or third person. (Only one lê is necessary in a multi-verb sentence, however.)

(As a corollary, first and third person subject pronouns are not necessary, and are included only for emphasis or contrast, or when conjoined.)

Ful chî kir eri olôntmâ.A conditional expression is formed using the subjunctive as well. There is no word 'if'; the condition is expressed using a participle (as in Caďinor):

I want my wife to be sorry.Ditt chî rênshtanmê.

I doubt that she'll come back.Laodê noê? Nozê.

Is it going to rain? It might rain.

Lê roi in gâtûta, lê lodê trai.With the indicative, the conditionality of these sentences disappears; they become statements of causation:

If you cheat [lit., you cheating] at dice, you will die.Il elorî sîk ezê in dom, ât fâ ku mashke âti.

If the king is not [lit., not being] at home, he is with his mistress.

A relative clause refers to a definite entity if it uses the indicative, to a potential or indefinite one if the subjunctive is used:Lê roi in gâtûta, lê laodê trai.

Because you're cheating, you're dying.

Il elorî sîk ezê in dom, ât ê ku mashke âti.

The king not being at home, he is (therefore) with his mistress.

Sa tênil naku kêt pêchâ boradhu er.Note that we cannot say il naku, because this usage of il requires a previous reference.

I am looking for the man who (I know) killed my brother.Sa tênil naku kêt pêchtri boradhu er.

I am looking for a man who (might have) killed my brother.

Finally, note that women (but not men) use the subjunctive as a polite imperative:

Shtanmê in dom êr azet! Come inside and sit down!

Prenmê nhê dinhe! Have some melon!

Prepositions govern the accusative. Some pedants, following Caďinor usage, distinguish between locative phrases (with dative) and adessive (with accusative); see Case usage.

a to, at, during khip under, below, till achu (away) from ko near, by, alongside akh against ku with, alongside, like ap using, with ôn among, at, within chint around pâkh almost, like dichi for, because of prêd before, in front of et about sa through(out) horad despite, although si on, on top of, above im in, inside sup after, following, since ish out of; made of tra across, over, beyond

Time expressions always use prepositional phrases (unlike Verdurian): a ôntru 'in the morning' (cf. Ver. utron), a mere khora 'at the third hour', sa nôchu 'for a night', khip kâdhue 'till ceďnare', sup il fiêtor 'after that evening'.

Il ekun fâ âlidên glûmu klât!female:

The prince was a little snot today!

Poche nikt âtô shkechubrâ shkebûr?

Why hasn't anyone strangled him?

Moru eri renlaodâ ish khichena beler.The particles are not used in writing (except of course when one wants to represent speech).

My husband is back from the front.

Sîk ê hakni ishgrima kerof e fôrim giro ish dhan hozdi.

It's not easy to get blood and horse dung out of wool.

(If you're wondering, queens use female particles, and butches use male ones.)

In origin, most of the particles are worn-down expressions: e.g. the solidary particle bra comes from boradh eri 'my brother'; the lamentative kokue derives from kaoku eza 'we are destroyed'; the compassion particle zâdhich is from hoz âdhich 'the god's mercy'.

If a sentence already has an adverb with pragmatic force (e.g. purho 'certainly', sîmeli 'not at all'), a phatic particle should not be used as well.

The particles listed are those common in northern dialect; they vary between dialects and tend to change over time. Foreigners are not expected to master the nuances.

As in Engish, double negatives are discouraged, and can be interpreted 'logically': Nikt krecha 'We ate nothing'; Sî nikt krecha 'We didn't eat nothing' = 'We ate something'. However, in areas with strong Verdurian influence, such as Hroth and the Western Wild, Verdurian-style double negatives with a single negative meaning are used, and there is a transition zone (the foothills of the Elkarin mountains) where they are avoided entirely.Sîk krecha ilî chinzikhî.

We didn't eat the gooseberries.Krecha sî chinzikhî, ak lomî.

It wasn't gooseberries that we ate, but apples.

Il elorê chilorê shkreve?In writing, however, the approved method (derived from Caďinor) is to replace the indicative of the main verb with the subjunctive.

The queen needs a beer?Chilorê shkreve shkê?

She needs a beer, does she? (f. pêza)

Il elorê chilormê shkreve?There is no question mark in the mountain alphabet; the period ends all sentences.

Does the queen need a beer?

A relative clause works about the same way. The relative pronoun (kêsht) normally follows its head noun.Rheda chî ezarzh eri sêth roi.

I believe that my steward is cheating me.

Saodor eri ê tênil naku kêt pêchâ boradhu tandê.As in Verdurian, but unlike English, verbs with sentential subjects don't need to be fronted:

My sister is looking for the man who killed our brother.Sâ kashki akh naku kêtô ukôrbâ boradh tandê.

I am hiding from the man whom our brother insulted.

Chî il elorî ê renê kaokuhmê zêth fichilê.

It's likely that the king is sloshed again.

Âdhi eshtûn (ku lê). Lê dan pe/belhu.

(Pagan greetings) The gods be (with you). May they give you peace/glory.

Eledha eshtê ku lê. Lê da pe/belhu.

(Eleďe greetings) Eleď be with you Eleď give you peace/glory.

(m) Lê ê shkê? Kêt shkê? Shtan bra. Az.

(f) Lê ê kêsht pêza? Kêt ê pêza? Shtanmê beler. Azet.

Are you there? Who is it? Come in. Sit down.

(For Shtan bra read Shtan ma (f. zêl) for a visitor of the opposite sex, or one not known very well.)

Kênz shtanê (p)? Dorovê (p). Sîk nhini (p). Mehmê é (p).

How are you? In good health. I'm not complaining. Same ol' same ol'.

Froê shtanê (p). Fôshtre no (p)! Âl adône ê pâkh rot (p).

It's cold out. Damn rain. This room is like ice.

Râdh leri sâ. Fichilâ meli facheka akh lê bra.

I am your servant. I look forward to good fighting with you.

(m) Or. Sîk ma. Epê eza. Sîk shkriva ma. Sîk kirez kirezêlî ilo kêshto klât.

(f) Or zêl. Sîk zêl. Epê eza. Sîk shkriva zêl. Sîk kirezmê kirezêlî ilo kêshto kherof.

Yes. No. Maybe. I don't know. Don't ask such questions.

Achel leri. Mûnite sâ (p). Fuch lerchê. Olontâ (p).

Please. Thank you. You're welcome. Excuse me. I'm sorry.

Subra dêna. Ôterâ lerî âluthî (p). Fichilâ foela beler. Meli facheka bra!

Till tomorrow. I know your virtues. I expect a letter (f/f). Good fighting! (m/m)

( The blessings given as greetings above can also be used when parting. Ôterâ lerî aluthî is a polite salutation for either sex; for men one may substitute lônd 'honor' or zôlant 'strength'.)

Tenî shkolî zônî (shkê/pêza)? Tena tedêsht e pao zônî.

How old are you? I'm 24.

Il khor ê kê (shkê/pêza)? Il khor ê pao shkiredach.

What time is it? It's 4 in the afternoon.

(m) Lê nomê shkê? Êk lhua ma. Leri pidi ê kônu shkê?

(f) Lê nomê kênz pêza? Êk lhua zêl. Leri pidi fâ kônu pêza?

What's your name? I love you. Your father is rich?

The gods' names in the days of the week have mostly been worn down to one syllable. In the Aďivro (and thus in rites deriving from it), fuller forms are used; e.g. Rhavkânach dên 'Rhavcaena's day'.

Days of the week Season Months of the year Barakhinei Verdurian Barakhinei Verdurian kândên scúreden demêtri (spring) olashk olašu shkirdên shirden rêslek reli fidordên fidren kirêndôn cuéndimar kaldên calten âshta (summer) feorêl vlerëi chirdên zëden kal calo therdên néronden rêshkulek recoltë kâdhu ceďnare kulek (fall) hak yag gelech želea ishkirêl išire hibreli (winter) shkor šoru froek froďac bâziand bešana

The fifth-year leap day, kasten in Verdurian, is kashdên.

Pagan names are still normally formed from two name elements, though names of gods, planets, virtues, and plants are also popular. The names are much less stereotyped than in Verdurian or Ismaîn-- there are still several hundred elements in common use, and almost anything in the lexicon is really fair game.

The table below merely gives a few representative samples.

Below are listed the most common Arašei (Cuzeian) names. These may be given to either Eleďe or pagan children. A + after a feminine name indicates a second declension name (accusative in -e). Masculine names ending in -i are declined as neuters.

Masculine Âdhdu god-given Elûtsan virtue lord Girôndkhum lion guts Kûbâkh righteous core Lôndorôth honor sign Parklêkh mountain fist Zôlpon strong warrior Bairel coyote Kehada emperor Keadau Feminine Arksâ bow woman Chivêkeler lively river Elirêli lovely melody Ilôdnôch silver night Klachhanta bright amber Noênhu rain-born Sonachilêl dream sky Idura longed for Kôlef the heroine Koleva

Eleniki names have only recently become popular, and are simply transliterated from Verdurian, ignoring the " accent: m. Adham, Klemet, Isac, Rhegoro, Vaseo, f. Agadhe, Kladha, Ihana, Prisha, Veachi, etc. The masculine names in -o are invariable, except for a genitive in -ro: Vaseoro 'Vaseo's'. Feminine names in -a follow the first feminine declension: Ihana Ihana Ihanê Ihanach.

Masculine Feminine Adairi Akor Alôda Alan Alôdel Âlu Ambrizi Anta Araz Ambek Ambriz+ Amizi Azena Banim Baor Brinim Bûzom Denur Barda Beret Bishberu Diazam Ekadit+ Ekin+ Bishbirakh Brinimi Chiveya Epet+ Etech Etinhi Dommava Dula Echeleda Feli Irizam Izech+ Ekuna Enach Enotiva Kaimeli Koelibo+ Lair+ Erês Fiôna Fisnava Laled+ Leret+ Leribod+ Irez Iriand Keloizi Luvor+ Muror+ Nhior+ Koelira Leria Lodikuna No+ Olezam Petinum Muror Namazi Olu Ridilênd Ruiz+ Salikhu+ Oraona Orom Pomikuna Siz+ Somezi+ Soren Remobû Samirêkh Saor Teroneli Tizati Ioret Solezi Sur Teronel Iûr+ Zeli Zien+ Zelizi Zid

The plays themselves fall into two categories: tales of adventure and romance (mirebeli), often retelling legends of heroes or tales from national history; or social comedies (ridibeli), satires of contemporary nobles, merchants, and clerics. The first are more popular with male audiences, the second with female ones. Troupes are often adept at tailoring a play to their audience, reserving their sharpest satire or frankest treatments of love for an all-female crowd, and toning down caricature and humor when particularly severe lords are in attendance.

Below is an extract from one such play, Lhumudrel by Benhêk of Barakhina, which explores the consequences of crossing gender boundaries; in this extract we see the title character (whose name means 'loves wisdom') inviting herself into a realm of knowledge meant only for men, that of Caďinor and its literature. Her father strenuously objects; though it is significant that he never suggests any alternative occupation-- noblewomen were not expected to work; there were servants for that. The consequences will later involve a flight from her husband-to-be, in disguise as a male. She falls in with, and eventually in love with, a wandering scholar-soldier.

There is a happy if implausible ending: the scholar turns out to be a lord, and her fiancé. Thanks to the structure of the play, Benhêk can express some fairly radical notions about women's worth, and freely satirize the prejudices of men-- the conventional ending will smooth any feathers that have been ruffled.

LHUMUDREL. Loda lelê chî teket shkrivê. Ihmêti nhêbor khurinî a habele zêl--

P. Nhêbor khurini, habelê ma.

L. Dinî khurinî a kurseleta dichi noz Alôdelach zêl.

P. Dini khurini, kurseletê ma.

L. E dhunî ôkhekî a ibru zêl.

P. Dhuni ôkheki, ibru ma.

L. Il habel fâ ish lanele adirê ku bôrd flavê, e fâ melhu domerê zêl, lê ful tô lelê pêza?

P. Kêtô lê fêti et ibru klât? Kê kêsht ibro ê shkê? Ridibel kokue, sîk eshtê thizi kêbrizê e kolaodê sachêi, ku eli nhêrulo shkebûr.

L. Ê ibor Gêremo.

P. Ibor kêti shkê?

L. Gêremo kêshtorîno zêl.

P. Sup ked zaa impiôn kêshtorîni Barakhinei meli shkê?

L. Ê kadhin meli lême, pidi. Shkrivû chî Gêrem ni im Barakhun pêza? A ilu kili fâ pedher Sua lême.

P. Kadhin meli ma! Sîk shpakh chî lê ûzê ibrê Kadhinu shkebûr!

L. Pidhiê meli foli. Klâtandu sêth komônê tô grima.

P. Sîk sêth plerê sîmeli. Chî redêlu ihmêta kôn ibroi tôshkê-- moru leri laodê shpakhê kêtô? Ak echilê shkrivê Kadhinu, ku chî lê eshtê medh klât! Kêt subrê shkê? Hashk chî lê laodê krêshki khuvî e sitele shkebûr!

L. Pidi eri, sîk kudiz. Ê prôshkalech, nikt ôtrê, dichi shkiredêi hibrelich, ked shkadrant el shkizant sîk zaa lelôn zêl êr ôterêli sîk zaa shtôn...

P. Sîk sêth shtanmê klât. Ê mankel eri, tô hashk-- sîk sâ êk ihmorêl. Sê zôdek midrê leriê, lê sêth komônê ku rêmant. Zeufol eza ma. Achupuu trator. Zêtê laodâ foka felâ klâtandula, e laoda farki shkeî kudekî ma.

L. Achel leri, pidi, sîk thiba sîmeli sêth morê zêl.

P. Achupuâ trator ma. Sîk laodâ tô etfetê ma. Kêshtorîni klât!

PIDI faichi.

L. Bunori somoch hozdi! Poche shpakhi il nom Gêremo pêza? Sû nomê nhê rizundula ridibelech ku-- ku Benhêk, saledhir kalatel foli. Âl khor laodâ manôdê moru êrât hozdi! E sêth pavôndê a nhê rhukh kedi sîk laodâ ôtera nikt, e kêt shkri kedi, tot epê ashkol rêth ôn parêi chî ibor el adlelek sî dêna zaa oîn, kadhin meli el ôtro rhono meli kherof! Zêth fut chî kêshtor dhirtê radu, ak lê, Gêrem, sê sêth chidêl in klerh zêl!

FATHER. I gave you fourteen gold pieces last month, daughter. How did you spend them?

LHUMUDREL. Let's see if I remember. I spent 9 khurin on a dress--

F. 9 khurin , dress.

L. 3 khurin on a candlestick for Alôdel's wedding.

F. 3 khurin, candlestick.

L. And 2 ôkhek on a book.

F. 2 ôkhek, book.

L. The dress was blue linen with a yellow border, and very pretty, do you want to see it?

F. What's this about a book? What sort of a book is it? Some silly comedy, I suppose, and not something edifying and suitable for women, like a saint's life.

L. It's a book by Genremos.

F. A book by who?

L. Genremos, the philosopher.

F. Since when are they printing philosophers in Barakhinei?

L. Oh, it's in Caďinor, father. Did you know Genremos was born in Barakhún? In those days it was the province of Su:as, of course.

F. In Caďinor! Don't tell me you can read Caďinor!

L. Only a little. The priest helps me work it out.

F. I don't like this at all. For a young woman to be spending money on books is bad enough-- what is your husband going to say? But to be trying to learn Caďinor, as if you were a boy! What next? I suppose you're going to grow balls and a beard!

L. Oh father, don't be upset. It's only a diversion for the winter afternoons, when there's no riding or shooting and people don't come visiting...

F. Well, I won't have it. It's my fault, I suppose-- I haven't married you off. You're a comfort to your mother, you help me with the accounts. Selfish of us. Put it off too long. Tomorrow I'll send for your uncle the priest, and we'll make up for lost time.

L. Please, father, I'm not in any hurry to get married.

F. I've put it off too long indeed. I won't discuss it. Philosophers!(Leaves.)

L. Oh, cruel fate! Why did I mention the name of Genremos? If I had named some writer of comedies, like-- like Benhêk, I would have just received a scolding. Now I am to receive a husband as well! And be carted off to some castle where I don't know anyone, and who knows where, perhaps so far up in the mountains they've never heard of a book or a play, in Caďinor or any other language! Philosophy is supposed to open the mind, but you, Genremos, you have closed me up in a trap!

Bunori somoch hozdi! Poche shpakhi il nom Gêremo pêza?

Samiosë Bunori! Prokio pavetnai so nom Žendromei?

Sû nomê nhê rizundula ridibelech ku-- ku Benhêk, saledhir kalatel foli.

Esli nomnai ti-crivece ridibodëi, com-- com Benëcan, santelece et ascele.

Âl khor laodâ manôdê moru êrât hozdi!

Nun tu sen dome otál maris!

E sêth pavôndê a nhê rhukh kedi sîk laodâ ôtera nikt, e kêt shkri kedi,

Er tu et nasitme ti-řükán ktë řo otermai nikto, er ke šri ktë,

tot epê ashkol rêth ôn parêi chî ibor el adlelek sî dêna zaa oîn,

eššane otal ret im parnen dy rho šrifcu nikagdá kio e ivro iy ralinë,

kadhin meli el ôtro rhono meli kherof!

im caďinán iy nibán otren řonán!

Zêth fut chî kêshtor dhirtê radu, ak lê, Gêrem, sê sêth chidêl in klerh zêl!

Zet ditave dy soa ripriroda tun uve so razum, ac le, Žendrom, ya et cüzre im áiočak!

It's worth noting that there are a good many more cognates than is apparent from this sample, but they are obscured by idiom and semantic change. The Barakhinei future (laodâ ôtera 'I'm going to know') would be understood in Verdurian, for instance, since a similar construction is used in Ctésifon (lädai oteran), and there is a Verdurian cognate to kêshtor 'philosophy'-- kestora-- but it is now limited to only part of the field, what we would call natural philosophy.

On the other hand, somoch and samiose 'cruel' are not cognates; the Barakhinei word derives from the name of the Somoyi, the nearest barbarians and former masters of the mountain realm; while the Verdurian word means 'merciless' (sam iosun).

|

| ||||||