| December 2014 |

|

| Walt Kelly: Pogo | |

I held off on reviewing Pogo for a long time, because it seemed too big to tackle. And now probably very few of you have even heard of it, so I’m going to have to start by explaining what it was.

You missed a bunch of good strips in the 1950s. For instance, these:

The basic setup: Pogo is a possum, one of a bewildering number of animals who mostly live in the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia. The major characters are Albert the gruff alligator with a penchant for accidentally eating the smaller cast members; Howland Owl the self-designated scientist; Churchy LaFemme, a turtle, the easygoing bad poet; the grumpy-with-heart-of-gold Porkypine; and Beauregard Bugleboy, the hound dog, ever proud of his abilities as a dog, never competent at exercising them. Pogo himself is a good-hearted patsy, always easy to cheat out of a free meal— though unlike Charlie Brown, he remains popular.

They all speak a dialect that starts out Southern, cycles through puns and malaprops, and ends up in double-talk. If you ever want to make a case for the untranslatability of certain kinds of literature, you can start with Pogo. (I read part of an Italian translation of Pogo; the translator evidently threw up his hands and gave up. It's written in very dull standard Italian.)

And when the wordplay isn't enough, Kelly starts playing with the balloons. His circus impresario P.T. Bridgeport speaks in circus posters; the fusty old Deacon Mushrat speaks in Old English lettering.

Where most strips, even good ones, keep circling the same old ground— I mean, I adore Watterson, but how many strips are devoted to the theme of school being boring?— Pogo was boisterously inventive. The characters would start a newspaper, or play baseball, or try to rescue a frog Albert had accidentally swallowed, or stage an old-fashioned duel, or dress in drag and blank out their eyes to parody “Lulu Arfin’ Nanny”, or attempt to master new-clear fizziks, or take turns romancing the unlikely belle of the swamp, the skunk Miss Mams’elle Hepzibah. Or outsiders would drop in: fast-talking mouse con men, flying bats looking for a home, cynical reporters for Newslife, even caricatures of Khrushchev and Castro. One year a few of the characters were blown by rocket to Australia, where Kelly could have fun drawing kangaroos and playing with the Aussie accent. Other times they'd sit around for weeks, jawing and bullshitting.

Kelly's first major dive into politics was running Pogo for president in 1952. He had a grand time with the faintly ridiculous bipartisan trappings of American politics— e.g. Albert rigs up a smoke-filled room by attaching a pot-belly stove to an outhouse. The next year he took sides, introducing Simple J. Malarkey to represent the Commie-baiting Senator Joe McCarthy. When a newspaper in Providence took offense and declared that the strip would be dropped if Malarkey showed his face again, Kelly had him put a bag over his head.

By the way, dig that art— meticulously drawn, with clear readable silhouettes and a mastery of facial expression.

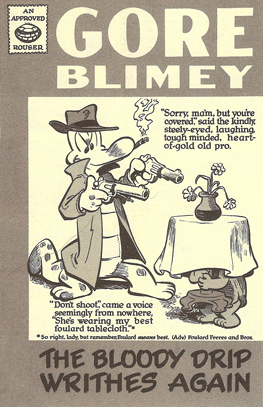

In the '50s, Kelly seemed to have superhuman energy. He merely started with drawing six dailies a week in minute detail, then went overboard with a splashy Sunday page. (As these were often self-contained slapstick sequences, they often ended with everyone literally overboard.) Then he redrew many of the strips to fit into published books, and added long additional sequences, often taking his characters into fairy tales, allegories, or satires. I treasure his pun-filled combination of mathematics and Mother Goose (played by Albert the Alligator), as well as “Gore Blimey”, his sendup of Mickey Spillane (played by Albert the Alligator).

Whenever my wife wants me to try on clothes, I have to quote Albert's line: ”Funny how a good-lookin’ fella looks handsome in anything he throw on.” Less often useful, but sometimes apropos, is “You've got a point, but your hat hides it.” Or “If I could only write, I’d write a nasty letter to the mayor, if he could only read.”

If you can find the books to read them (and good luck with that), what will probably first strike you is Kelly's unruffled good humor. Like Pogo, he seems to like everyone, and his idea of a good time is a bunch of friends sitting around at a “perloo”, drinking, eating, and joking. But then you’ll notice the comedy of manners: Pogo's friends turn out to be selfish, lazy, greedy, and self-important. They take advantage of Pogo, then look down on him for being so easily taken. A running joke is that the women of the swamp, especially Miz Beaver, are far more competent than the men, and just as sharp-tongued.

Sometimes the strip is a glimpse into an earlier America— a slightly disreputable place occupied by newspapermen, tramps, circus men, traveling salesmen, gamblers, vaudevillers, raconteurs, and con men— all trying to get ahead, never quite making it, but always willing to set a spell and spin tall tales. The prototype here is the fox, Seminole Sam. In the early days of the strip he was occasionally a villain, more often a smooth-talking fraud who happily sells Beauregard a bottle of H2O as a universal elixir. He could be a less prosperous precursor to Garry Trudeau’s Uncle Duke.

Kelly could be roused by the evils of the day, from McCarthyism to pollution, but he was always conscious that even evil people are people, and the good are never untainted. Thus his repeated motto, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” (By now this is probably more famous than the military communiqué it's based on: “We have met the enemy and he is ours.”)

The Southernness of the characters is, so far as I can see, part of an old Northern trope, seen also in Li'l Abner, Mayberry RFD, and The Dukes of Hazzard: small-town Southerners were seem as parochial and uneducated, and yet as a repository of old-timey virtues. It's a vision which completely ignores race, of course. Kelly was on the right side of the civil rights movement, but he only dealt with politics when he saw fun in it, and he seemed to sense that this subject was dead serious. (It also occurs to me that a familiarity with Southerners might have been more common for Democrats back when Southerners, warts and all, were part of the Party.) On the plus side, since the characters are all animals, you can’t say that he didn’t depict any black characters.

Kelly even ventured into comics criticism… I couldn’t top Churchy LaFemme's analysis here:

See also: Animating Pogo

| Jamie Delano / Garth Ennis / Peter Mulligan: John Constantine, Hellblazer | |

I first ran into John Constantine as a minor character in Sandman, and then in The Books of Magic. Then, in one issue of Planetary. Even these brief appearances were enough to show his character and his charisma. Like Catwoman, he's a character that's somehow better than any of his particular appearances. He's a cheeky working-class Englishman who knows a bit about magic. Not a wizard— he's not the studying type and couldn't give a hoot about power. He just kind of runs into it, and keeps his head when it's about, and calls supernatural entities “chum.”

I first ran into John Constantine as a minor character in Sandman, and then in The Books of Magic. Then, in one issue of Planetary. Even these brief appearances were enough to show his character and his charisma. Like Catwoman, he's a character that's somehow better than any of his particular appearances. He's a cheeky working-class Englishman who knows a bit about magic. Not a wizard— he's not the studying type and couldn't give a hoot about power. He just kind of runs into it, and keeps his head when it's about, and calls supernatural entities “chum.”

Abraham Riesman has a lovely article where he goes through the creation of the character and all his various chroniclers— it'll make you want to read it all. (I also hadn't realized that Warren Ellis, who wrote Planetary, had just come off a run of Hellblazer.) So I picked up four volumes of Jamie Delano's run.

Verdict: well, it's reminiscent of the first volume of Sandman, back when it was heavy on the nameless horrors and frankly subpar on the art. (I skimmed through two volumes to find the nice scan at right… really, most of the art is embarrassing.)

John deals with devils, doomsday cults (tied not very subtly to Thatcherism), serial killers, and the Swamp Thing's love life. (Really.) Delano removes some of the mystery (we meet John's father, we hear about his early life as a punk rocker and teenage occultist), but he also gives John a certain fateful tragedy (people close to him tend to end up dead), and he suggests that John— though he is not infrequently terrified or out of his league— at some level gets a kick out of horror.

A two-issue sequence called “The horrorist” shows the series at its best and worst. The story is that a young woman has the ability to show people the evils and horrors of the world, so vividly that they’re compelled to kill themselves. John tracks her down, has sex with her, she lays the trip on him— and he kinda likes it.

As a character portrait, that's amazing. John isn't the Batman of the arcane; he's a bit of a dick, and a bit of a con man. Reisman says that Alan Moore conceived of the character as a “wide boy”— what Americans would call a hustler. Not entirely unlike Seminole Sam, then. (Bet you thought I couldn’t make a connection with Pogo.)

The story (and the series) dwell the dark side of life: the real horror, it reminds us, isn't a bunch of invented demons, it's what real human beings do to each other. Or is it just exploiting all that— showing us horror porn so we can, like John, condemn it while getting a thrill out of it? I don't know, and maybe it's all right anyway. Gaiman's first Constantine story (in Preludes and Nocturnes) is definitely horror porn; maybe the difference is that Gaiman is just a better writer. Delano litters the page with a running narration from Constantine, and it rarely adds much.

The other thing is… I like Gaiman's and Moore's excursions into magic and fantasy, but all too often the trope writers use to get there is that traditional magic, from John Dee to Aleister Crowley, is real. It makes for some good stories, but it gives way too much credit to narcissistic old charlatans like Crowley.

(There's a new TV series out based on Hellblazer. I have no idea what it’s like, though I note with approval that the actor is British and looks like Constantine. The 2005 movie starred Keanu Reeves; now that’s horror for you, chum.)

I've now read a bunch more Hellblazer. And it gets better!

I've now read a bunch more Hellblazer. And it gets better!

First, a few volumes written by Garth Ennis. These start out with a bang: he gives Constantine a fatal lung cancer. Well, serves him right, all that smoking. Constantine considers just letting it carry him off, but then decides to not to gentle into that good night: he calls in a few debts to supernatural beings. Finally he ends up dealing with— and tricking— the three Lords of Hell. (DC cosmology starts with Catholic doctrine, then one-ups it with constant plot twists. So, yeah, at this particular moment there were three demons ruling Hell. No, not Lucifer, he'd quit. It gets complicated.)

Anyway, stories of people tricking the devil are always fun. But the best bit is that Ennis is just a better writer. Which doesn't mean, in this case, that his sentences are better or his plots more sophisticated; to a large extent what he's done is simplified the book. He doesn't have Delano's long goth-poetic narration; he doesn't pretend to tell you something about the viciousness of the human species. It makes for more satisfying stories. I'm not sure real horror works in a comic book (how shocking can a drawing of intestines ever be?), but Constantine works very well as a sort of noir tall tale about magic and demons.

There's an extended sequence where Ennis tears Constantine apart— his girlfriend leaves him and he turns into a homeless alcoholic. This is less successful, especially as when he's Learned Something, John just gets some money by magic and rejoins regular life. According to Reisman, Ennis ended up disliking Constantine's character— he was too much of a bastard. But, well, that's pretty much what makes him work as a character.

Next, a couple volumes by Peter Milligan, who once worked on Tank Girl, of all things. He turns out to be pretty good at writing Constantine! He sends him to India, which could have gone terribly wrong— but Milligan deftly navigates British colonialism, Hindu demons and sages, and the contradictions of modern India. Then there's another send-Constantine-through-hell volume, centered on Constantine getting married, of all things. It gets a little over the top, but it hangs together and even ends rather sweetly.

It doesn't hurt that the book finally got some good artists. The Ennis books are well done, but the Milligans are very nicely illustrated indeed. Giuseppe Camuncoli and Stefano Landini have a nice stylized look, while Simon Bisley (who did the panel above) is amazing. That face and expression for Constantine are perfect: tough, scarred, but with a gleam of cold humor. (Also, older. Constantine is one of the few characters who've been allowed to age in real time. At least until the last reboot.)