| April 2015 |

|

| Étienne Davodeau: The Initiates | |

Two comics reviews just four months apart? It’s like the heady days of 1997 all over again! They’re similar in many ways: both are straight-up storytelling, with an emphasis on realistic though often sketchy drawing. And they’re both about artistic passion. They’re also both fairly long— this one is 264 pages.

The Initiates has a simple premise, laid out in the subtitle: “A comic artist and a wine artisan exchange jobs.” Well, they don't do each other’s jobs, really. The artist, Étienne, participates in all the hard work of the vineyard, while the vintner, Richard Leroy, simply reads a lot of comics and meets some editors and artists. Ensuring his popularity, Richard always brings a few bottles of wine along.

The Initiates has a simple premise, laid out in the subtitle: “A comic artist and a wine artisan exchange jobs.” Well, they don't do each other’s jobs, really. The artist, Étienne, participates in all the hard work of the vineyard, while the vintner, Richard Leroy, simply reads a lot of comics and meets some editors and artists. Ensuring his popularity, Richard always brings a few bottles of wine along.

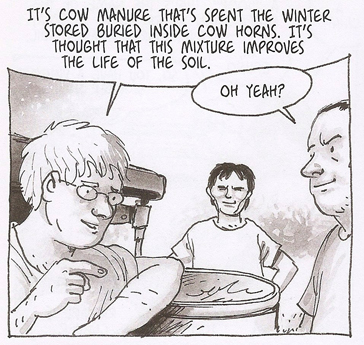

On the whole it’s not deep, but it’s charming. You’ll learn a lot about winemaking: the months of pruning, laborious days of weeding and harvesting, days spent in the cellar checking on barrel after barrel, and endless tasting. The main parallel that Étienne discovers in their two fields is geekiness. Richard is a wine pedant— he’s a terror to waiters, scrutinizing wine lists and croaking out “water” when nothing meets his approval. His vineyards are organic, he has a thing about using as little sulfur as possible, and he follows a somewhat quackish discipline called “biodynamics” simply because he thinks it makes the wine taste better (and, one suspects, because it adds to the laboriousness). There’s a semi-comic chapter where an emissary of the American wine expert Robert Parker visits Richard’s cellars, tasting solemnly and refusing all conversation. At least Richard seems like good company— he seems to be an unflappable character.

The sections on comics are not as satisfying. We hear what Richard thinks of a few classics— he’s impressed by Maus but not by Moebius— but neither of the two offer any great insights on the medium or the books they like, and we see nothing of Étienne’s own methods or struggles.

The one thing that comes through is what strikes me as a very French attitude toward both crafts. They’re both laborious, quirky, individual, and the French attitude is to take them seriously and do them as well as possible without worrying about the economics— even if the reward is ultimately only a subjective aesthetic experience.

As a story… well, it doesn’t really have one. There’s no conflict; no one has any great revelations. We learn that Richard is married and has a son but never meet them. But take it as non-fiction, like a New Yorker profile done through cartooning.

We could ask, though, why is this a comic rather than, say, a magazine article? There are passages that are mostly exposition or dialog, and I don’t know that the medium shines here. On the other hand, if you have to explain a mechanical process, or simply evoke the French countryside, the drawing is communicative in a way words alone can’t be. It’s a heroic effort, making all those drawings, but sometimes I think we need a convention that the story could occasionally veer into text. Dave Sim and Alan Moore have tried this. Changing the tempo is a bit jarring, but it might fit stories like this. Not that there’s anything wrong with Davodeau’s method— it’s an easy read, even if you do get a little too many pictures of people drinking wine while they talk.

Interesting cultural point: Davodeau provides a list of the wines drunk and the comics read. 41 comics, of which 32 are French, and just 2 are non-Western. The French give Americans a run for their money in giving the impression that there’s not that much need to leave your own linguistic sphere.

| Scott McCloud: The Sculptor | |

McCloud strongly hinted in Making Comics that he wanted to delve into serious storytelling, and he has. This is a tome, nearly 500 pages long. Also, it’s a tragedy.

McCloud strongly hinted in Making Comics that he wanted to delve into serious storytelling, and he has. This is a tome, nearly 500 pages long. Also, it’s a tragedy.

Er, it’s going to be hard to talk about the book without avoiding spoilers. I’m not going to spoil the ending, but if you want to go in cold, go read it and come back. I’ll still be here. Oh, and don’t read the back cover.

So. The setup is: David Smith is a sculptor… not a very good one. He runs into his grand-uncle Harry, has a grand time reminiscing, then complaining about how everything has gone badly for him, and then remembers that… Uncle Harry is dead. This isn’t Uncle Harry… exactly… it’s Death. And he offers David a deal: he can have superpowers as a sculptor… basically he can mold raw materials into any shape he can imagine. The price is his life: he will only have 200 days to live. What could go wrong?

There’s a lot to love about The Sculptor. It’s long enough that McCloud can take his time with the story. It has some spectacular vistas of New York. It avoids being a success fantasy— David actually has a lot of trouble making something out of his gift.

I assume it’s intentional that David is a bit of an asshole. He alienates his friends and patrons, he’s a bit of a blowhard about art, he’s self-righteous about keeping promises, he can’t let it go when his best friend gets into what he considers an exploitative relationship. And the very fact that he accepts Death’s deal is probably a sign of suicidal depression, not greatness. It’s normal for the protagonists of books to be flawed or worse, but still something of a rarity in comics.

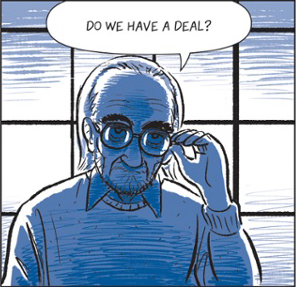

I liked what McCloud did with Death (at left). He adopts the old idea that Death can occasionally live an ordinary human life; here he replaced a young man— the actual Uncle Harry— and lived out his life. So he’s a bit of a supernatural presence, a bit of a kindly old uncle, and something of a tragic figure in his own right— he’s fading, losing his connection to the human world. He’s also the best drawn of the characters.

I liked what McCloud did with Death (at left). He adopts the old idea that Death can occasionally live an ordinary human life; here he replaced a young man— the actual Uncle Harry— and lived out his life. So he’s a bit of a supernatural presence, a bit of a kindly old uncle, and something of a tragic figure in his own right— he’s fading, losing his connection to the human world. He’s also the best drawn of the characters.

(McCloud’s drawing is very variable. Sometimes he’s impressive; sometimes he’s clunky. This should probably bother me less than it does; I enjoy some far cartoonier artists, like Lewis Trondheim. I wanted him to blow me away, as he did on several pages of Making Comics. He does have some really nice images, but they’re mostly the ones I’ve already seen in publicity for the book. His use of two colors is beautiful, though.)

The major problem with the book is David’s love interest, Meg (at right). The problem is that she’s a total manic pixie dream girl. It’s obvious that McCloud was told this, or worried about this, because she or her friends are always telling David that she’s a real person with her own problems, not a muse, not a repository for his obsessions. Yet she is a muse, she’s almost always perky and supportive and wise, she grounds David and gives him something to live for, and the book is alway his story not hers. She’s depicted as something of a rescuer— all her friends tease her about it. I know women like that, and it’s not cute at all… men who need rescuing are men with problems, and merely having a girlfriend doesn’t solve them.

David convincingly evokes the desire to create, but the very nature of his superpower means that we never learn about sculpting, as we learned about wine-making in The Initiates. It seems like an adolescent vision of art… when you’re a teenager you want to have created things, so Uncle Harry’s gift would be just what you want. Bing, you’ve made a sculpture, a symphony, a novel! But why did you make that thing? What was the process of making it? David has a passion to make things, to be famous, but his passion doesn’t seem any more focused than that.

At the end he does make one very meaningful sculpture. But this is just substituting a Hollywood version of art: we know what that sculpture means because we know his biography. What if we didn’t? If we knew nothing of David’s life, would that particular sculpture be impressive?

On the other hand, McCloud may be playing a meta game on us. What if you had a superpower, a major one, one that you thought you wanted, and it just didn’t work out for you?