|

| ||||||

Phonology — Consonants — Vowels — Stress

Morphology — Verbs — Progressive — Imperative — Participles — To be — Nouns — Pronouns — Numbers — Derivations

Syntax< — Sentence order — Ergativity — Conjugation — Prefixes — To be — Participles — NP order — Yes/no questions — Negatives — Adverbs — Existentials — Possession — Indirect objects — Conjunctions — Prepositions — Interrogatives — Auxiliaries — Valence change — Relative clauses — Sentential arguments — Place and time — Conditional — Comparative

Semantic fields — Names — Titles — Kinship — Greetings — Horses

Sample texts — Baburkunim — Book of the Emperor — Who is the Emperor?

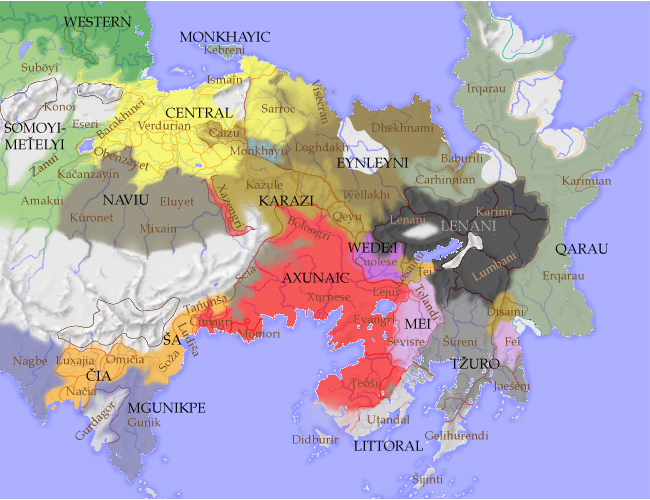

The Lenani-Littoral language family is divided into three branches:

Its followers, Jippirasutum, study the words of the prophet Babur, the Baburkunim (‘Babur spoke to us’). The very words of the book are holy, and thus define the Classical Tžuro language (CT). The modern Tžuro languages can all be taken as deriving from CT.

More precisely, CT is the language of classical scholarship, especially the Čelepa s Atej (Emperor’s Book), completed in 2391 under the Anajati Tej. The Baburkunim is published with spellings ‘corrected’ to Anajati norms, but contains lexical and morphological archaisms.

CT remains the standard literary language of Šura, and one of the three major working languages of the Democratic Union (DU), along with Mei and Lenani. But this statement requires many hedges.

Spoken Šureni (SŠ) has of course changed significantly in the 1300 years since the Anajati, and the 2000 year since Babur. This mostly affects the phonology, but in predictable ways: you can generally deduce the modern pronunciation from the written form, though not vice versa. There are also morphosyntactic changes, and of course many lexical changes.

Literary Šureni (LŠ) is what people write in the 3600s. This in turn has several registers. A preacher or theologican may attempt as close an imitation of CT as they can manage. The language of a journalist or novelist is much more influenced by SŠ norms, and freely uses modern terminology and slang. Informal communications may be almost pure SŠ.

There are finer nuances still. The preacher is not free from modern influences, and “modern CT” is easily distinguished from ancient literature— for instance, by the frequency and meaning of various verb forms. At the same time, the popular writer will make use of CT quotations, or use CT syntax for rhetorical effect.

All this will be familiar to students of Latin, Arabic, or Chinese. Medieval Europeans, or modern Arabs, wrote in a literary language standardized more than a millennium before— but Isaac Newton does not write like Cicero, nor a modern Cairo newspaper like Muħammad.

For ease of exposition, this grammar covers CT only. Modern LŠ and SŠ are described here. Admittedly this will be awkward if you are chiefly interested in the modern language, but it saves writing a very confusing discussion of changes and exceptions in every section of the grammar. For what it’s worth, knowing CT is excellent preparation for learning LŠ or SŠ; going the other way is far more difficult.

—Mark Rosenfelder, December 2022

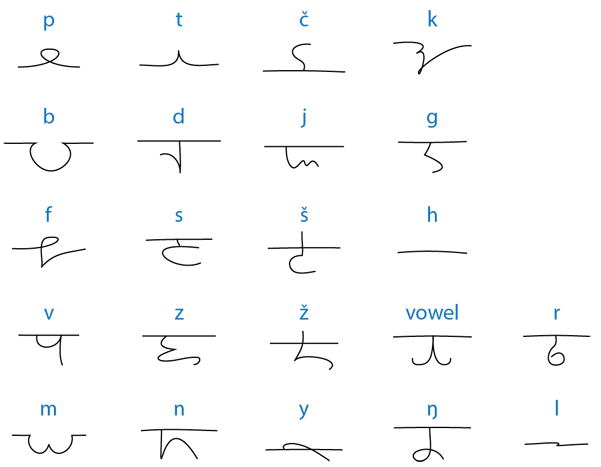

As a first approximation, consonants can be taken as their IPA values, except that č j š ž are /tʃ dʒ ʃ ʒ/.

labial lab-dent dental palatal velar stops p t č k b d j g fricatives f s š h v z ž nasals m n ŋ liquids l y r

Tžuro usually borrowed OS dental stops with their own (e.g. dleda > drida, Kolatimand > Kulatiman), and OS retroflexes with their palatals (seṭṭeş > sačaš), which suggests that t d s etc. were indeed dentals and not alveolars. The recitation manuals confirm that these consonants (except r) were pronounced with the tongue against the teeth.

Evidence is unclear on whether r was an alveolar tap [ɾ] or a retroflex [ɽ]. OS r was borrowed as r, but there was no other alternative. SŠ has [ɾ].

Like French, voicing begins early in the voiced consonants; to outsiders, a word like Babur sounds almost like Mbabur. The cluster tž thus contrasts with both č (which is unvoiced throughout) and j (which is voiced throughout).

An h at the end of a syllable must be pronounced.

Doubled consonants should be pronounced longer.

front back high i u mid e o low a

SŠ is characterized by diphthongization of stressed vowels and reduction of all others. The manuals do not mention any of this, and it’s likely that these changes postdate CT. There is weak evidence that the mid vowels were laxed in closed syllables, thus kome = [kome] but johdeg = [dʒɔh dɛg].

If the last syllable ends in a vowel, don’t stress it: FSAva, TŽUro, KRUna, MAli, KOme, maRAmu.

Don’t stress morphological prefixes or suffixes: aTEJ, MOLon, JIPpir, JEŋum. The place suffix (v)ali is an exception: duVAli. Naturally you will have to learn what these affixes are to recognize them!

Compounds have secondary stress on the first compound: Jippir-asti – JIPpir Asti, Fanal-nak = FAnaNAK, Babur+kanum = baBUR KUnim.

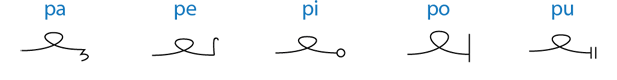

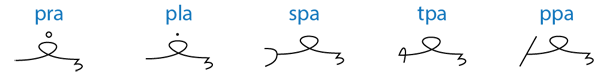

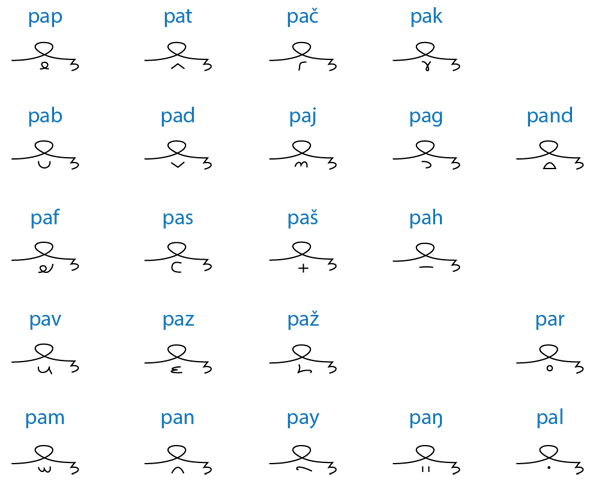

The ppa diacritic is used for a preceding geminated consonant. (I.e. applied to tu it produces ttu.)

Finally there are diacritics for final consonants, generally related to the base letterforms:

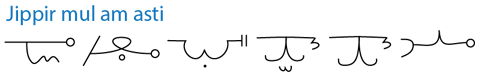

Here’s an example putting all these things together:

There are no spaces between words, but it’s preferred to begin a word with a new tatit. Thus you don’t write the above sentence as …mu la ma sti.

A consonant letter can be used on its own if needed for an unsupported initial cluster, as in jreta or švari. These are quite rare, however.

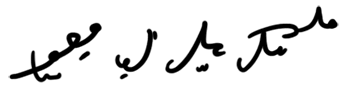

The above letterforms are prototypical, but there are variants where each CV syllable can be written in one stroke, and where syllables can be connected. For instance, here’s a more calligraphic version of the above sentences:

Tžuro orthography does not have anything corresponding to our hyphens or even our spaces— though stress is marked. We could write (say) karaklujur ‘those wars’ equally as karak-luj-u-r or karakluju-r. I’ve preferred not to use hyphens, simply because that will make discussion of LŠ changes easier.

The citation form for verbs is the 1s absolutive, e.g. kini = “I was spoken to.” The verb agrees with both agent (using the ergative infixes) and experiencer or patient (using the absolutive endings).

Mnemonics:

Absolutive Ergative Reciprocal Singular I mali mil mili you mala mal mala he/she malu mul mulu Dual we two malis mzil miliš you two malas mzal malaš they maluz mzul muluš Plural we malim mailin you all malah mol molon they malum maul maulan

It’s formed with an infix, most often r, but this can vary by verb (and often exposes a pre-Tžuro form of the root). The lexicon gives irregular active participles, which will have the same infix as the progressive. If a root has three consonants, the middle one becomes the infix: hasti > hisit ‘I am reading’, traki > tirik ‘I am dropping’.

Mnemonics:

Absolutive Ergative Reciprocal Singular I mrali miril mirili you mrala maral marala he/she mralu murul murulu Dual we two mralis midil midiliš you two mralas madal madalaš they mraluz mudul muduluš Plural we mralim maril marilin you all mralah marol marolah they mralum marul marulan

If the C is an affricate, the second C will be the corresponding stop: sači ‘be correct’ > sačutu ‘correct’; nuji ‘know’ > nujutu ‘known’. If the C is ŋ, the second C is g: moŋugu ‘afraid’.

Occasionally the participle is simplified: soti ‘clean’ > *sotutu > stutu, draji ‘divide’ > drajju ‘divided’.

Stress falls on the penult: saČUtu, STUtu

An active participle is formed like the progressive, with the infix -VRa-, with the V being the vowel of the citation form of the verb, and R being the infix used for the ergative progressive. Thus jiraŋ ‘eating’, kišan ‘speaking’, nebat ‘teaching’, tezat ‘cutting’, sorat ‘cleaning’, daraj ‘dividing’.

If the verb ends in a double consonant -DC, R will be D: naŋgi ‘trick’ > naŋag; sarni ‘cook’ > saran.

Irregular participles are given in the lexicon. (E.g. sizi ‘advise’ > sinas not *siraz, tezi ‘cut’ > tensu.)

The participles can take prefixes: ujiŋugu ‘eaten in the future’, pastutu ‘unable to be cleaned’, nikišan ‘able to speak’.

Past Progressive Singular I ši sič you ša sač he/she šu suč Dual you + I sris sid you two sras sad they sruz sud Plural we srim siš you all srah soš they srum suš

ajjos > ajjoso kingsIf it ends in vowels a/e/i, add -u:

atej > ateje emperors

čal > čala seas

fsava > fsavau clansIf it ends in vowels o/u, or in ei, add -m:

mahi > mahiu wheats

jeŋu > jeŋum godsThere are some irregular plurals as well, noted in the lexicon.

sovei > soveim aunts

A genitive is formed with -i, for either singular or plural:

ajjos > ajjosi king’s, kings’The demonstrative ending r and the possessive suffixes also apply to nouns; see below.

atej > ateji emperor’s, emperors’

fsava > fsavai clan’s, clans’

mahi > mahii wheat’s

jeŋu > jeŋui god’s, gods’

Min and teŋ come from the words for ‘under’ and ‘over’. Their plurals are regular.

s pl poss I min mini -li you teŋ teŋe -la he/it so sono -su she soŋ -suŋ

There is a gender distinction only in the 3s— sono pluralizes both.

The pronoun zal (from ‘mighty’) is used for kings, gods, and nobles, by everyone present. So e.g. Jippir calls himself zal, and he is addressed zal in prayer, and referred to as zal. However, only one person in a conversation can use zal— the highest ranking one. Thus a noble talking to a king cannot use zal for himself, only for the king.

The possessive suffixes are added to nouns: ajorli my lord, grejali my house, grejala your house, tejsu his emperor, jejitsuŋ her child. These serve for plurals as well— grejali could also be ‘our house’. There is no suffix for zal.

With -su(ŋ), after š ž, z, s > š (teššu ‘his leather’), and after č j you just prolong the final stop (ločču ‘his park’, phonetically lotču.)

“That man, that place, that day” have all fused, producing mar ‘that (one)’, čer ‘there’, ner ‘then’.

These words in turn can be used with the possessive suffixes: marli ‘this one by me’, marla ‘that one by you’, marsu ‘that one by him.’

Here and with the quantifiers, persons and things are not distinguished: ava is ‘who’ or ‘what’. These terms are only used for questions. The relativizers are jo ‘that’, nejo ‘when’, čeŋo ‘where’, explained in the Syntax section.

which au who ava where avali when aunem how audeg why avar how much aumerg

In English ‘other’ and ‘many’ are considered ordinary adjectives, but gok and kuš fit in with this system of pronouns and have noun/place/time derivations.

adjective noun place time none let lettir čelet nelet one mo mot čemmo nemmo other gok gokkir gokali neŋgok some/any biva bivat bivali nembiv many/much kuš kuššir kušali neŋkuš all/every an anat čegan neman

The ‘one’ row can usually be taken literally— e.g. if you say you have mo jejit it means you have just one child. But sometimes it’s used for ‘one or more’, or simply means an indefinite references (‘a child’). Pragmatically, biva is used for ‘two or more, but a small number.’

In the primitive system, numbers up to 36 were formed with the formula U a-ma-P where U is the units and P the power of 6; thus 22 = 346 = dala amadej. 36 (1006) had its own root, dah. The numbers 7, 9, and 11 are worn down slightly, e.g. momah < mo a-mah (which in fact is attested). The numbers 8 dag, 10 pis, 12 mog were borrowed from OS darg, pisan, morg.

unit x6 x12 nth 1/n 1 mo mah mog ništi 2 ŋok mog madala lešpi drajutu 3 dej madej dah lendi neja 4 dala madala mogdala jreta 5 biŋ mabiŋ mogbiŋ joma 6 mah dah mogmah 7 momah mogmomah 8 dag mogdag 9 dejmah mogdejmah 10 pis mogpis 11 bimah mogbimah 12 mog ged

Numbers above 36 are formed with the OS-based formula mog-T a-U where T is the power of 12; thus 70 = 5T12 = mogbiŋ apis. The powers and units thus switch positions after 36.

Higher powers of 12 are borrowed from OS (ged 144, ruŋ 1728, demun 20,736).

Ordinals beyond ‘3rd’ are formed like the genitive: dalai ‘fourth’, dagi ‘eighth’, etc.

Fractions beyond 1/5 are formed with the orginal plus drag ‘part’: mahi drag ‘1/6’, mogi drag ‘1/12’.

Basic arithmetic:

ŋok a dala suruj mah two and four touch six 2 + 4 = 6 dag let dej suruj biŋ eight not three touch five 8 – 3 = 5 ŋok tot dala suruj dag two with four touch eight 2 x 4 = 8 mah draga ŋok suruj dej six parts two touch three 6 / 2 = 3

Process: iCVCa

galni > igalna confusionState: CVCat

čuk empty > čukat emptinessActor: aCVC

depi judge > adep judgeFeminine: ŋ-; before a consonant, eŋ-

tej empire > atej emperor

asev uncle > ŋasev auntDefinite person: CVCCir

adim lover > ŋadim female lover

muka deer > eŋmuka doe

teŋ over > teŋŋir saintPerson with a quality: CVCei

jipi demand > Jippir name of God

Attafei all-mighty-oneDevice: CeC

Janei northern-one

časki stab > česk rapierObject: CaRaC

gaji lie down > gej bed

braji put, set > baraj buttocksPlace: CVCali

kanki divide > kanak wall

sizi advise > sanas council

depi judge > depali courtPassive participle or adjectivization: 3s + reduplicated final syllable:

duvi cross > duvali crossing

mefi ‘think’ > mefufu ‘thinking’City: -im

soti ‘clean’ > stutu ‘clean’

Jippir God > JippirimDiminutive: -it

jand north > Jandim

dega dress > degit skirtAugmentative: -luj

hol horse > holit foal, small horse

karak fight > karakluj warStudy: -nuja

suk nose > sukluj big nose, angry man

šej animal > šejnuja zoology

nehi move > nehnuja physics

man nation > mani nationalSometimes -ndi:

Gučidak Gurdago > gučidaki Gurdagor

nata leaf > natandi leafyQuality: often -ig:

pašma despot > pašmandi despotic

bandi wonder > bandig wonderfulAbility: ni + active participle

got command > gotig demanding

lon water > lonig watery

jiši see > nijišat visible; able to seeInability: pa + active participle

jiši see > pajišat invisible; blindLikeness: genitive + -deg

maran mother > marandeg motherlyNegative: -ja

stutu clean > stuja unclean

mefi reason > mefija irrational

baŋi harm > gobaŋi alleviate sufferingCausative ye-

jipi order > gojipi countermand

muli say > gomuli deny

ham black > yehami blacken

jaki be born > yejaki bear a child

See also the section on Names.

Jippirasti I listened to Jippir Baburkunim Babur he spoke to us dugmuju it goes, it twists itself = snake turuk it makes it fall = arrow for felling horses

Kurund akaraka kunum.But this is cheating a little, as one argument is singular and one is plural. Kurund Kutaj kunu ‘Kurund spoke to Kutaj’ and its variants would be ambiguous.

Kurund fighter-pl speak-3s>3p

Kurund spoke to the soldiers.Akaraka Kurund kunum.

Akaraka kunum Kurund.

Kurund kunum akaraka.

Kunum Kurund akaraka.

Kunum akaraka Kurund.

(In the gloss, 3s>3p should be understood ‘third person singular acting on third person plural.’)

Let’s back up a bit. Kina is a complete sentence in itself, and needs no arguments: I spoke to you. Likewise Kani you spoke to me, kinu I spoke to him/her, kzilas the two of us spoke to the two of you, kauna they spoke to you.

With third person arguments, you will want to give the referent at some point. However, where you put it has a pragmatic meaning. In general you introduce arguments by placing them after the verb, while existing arguments appear before it. Thus:

Kištu paran.This is roughly how we use the definite article, and I’ve translated accordingly. But there are nuances.

kill.1s>3s male

I killed a man.Paran kištu.

male kill.1s>3s

I killed the man.

One, the argument precedes the verb if it’s being mentioned incidentally:

Dega ŋiršu.The speaker is just saying what she was doing; there is no intention to focus on the dress or talk about it further.

dress buy.1s>3s

I bought a dress.

Two, there is no need to introduce things that are always there: cities, the sun, the sea, God, etc. Thus these normally appear first:

Jippir kunu.If we reversed this (Kunu Jippir) the implication is that it is news that Jippir spoke.

God speak.1s>3s

Jippir spoke to him.

A corollary of these two rules is that when a scene is introduced, things that normally belong to that scene can be taken as existing. E.g. here a city scene is evoked; streets are part of a city and thus are treated as existing background:

Degi rut im. Lujaliu čuku.If there are 1st or 2nd person arguments, or arguments are understood from context, there will be one argument at most. But of course two arguments are possible. From the above rules, we expect that an existing referent will precede the verb, a new one will follow it:

go.>1s to city / street-pl empty.>3s

I went to the city. The streets were empty.

Ŋamaššu yejuku sadat.This sentence is felicitous if the speaker is introducing the son, and has mentioned the wife (or the husband) previously.

woman-3sm.poss bear-3s>3s boy

His wife bore him a son.

If we’re introducing two referents at once, both appear after the verb, and the agent comes first:

Kunu Helu Janei.If we’re already talking about both parties, both could appear before the verb; but now the agent comes last. It may be less confusing to recall that the agent is closer to the verb.

speak-3s>3s Helu Janei

Helu spoke to Janei.

Janei Helu kunu.Is this what the grammarians meant by free word order? (You could invent a context for each of the six possible orderings.) Not precisely, because we can also speak of rhetoric and poetic license. In everyday speech the above rules would suffice, but in elevated contexts one might pursue surprise, or emphasis, or momentary confusion— or a particular ordering might fit the meter better. I can’t advise that foreign learners play with such things, but I don’t want you to be confounded by unexpected word order in texts.

Janei Helu speak-3s>3s

Helu spoke to Janei.

A verb with just one argument has a valence of 1; we call it intransitive. The argument is called an experiencer.

Examples: The king walked; I slept; the shoe dropped; you died.A verb with two arguments has a valence of 2; it’s transitive. The more active argument, the one doing the action, is the

Examples:For case systems or verbal agreement, we can group these in several ways, but these two are common. (If it’s not clear, I colored the cases by combining colors: blue +the king hateshis minister ;I lovemy wife ;you readthis book ;she firedthe cannon .

English doesn’t have morphological case on nouns, but it has syntactic case:Sadata bau ču tasat .

boy-pl break.3p>3s window

The boys brokea window .

Tasat baču .

window break.3s

The window broke.

In CT, the window has the same case in both sentences,

Often Tžuro has one verb where English has two. Compare:

That is, one word kašti serves for both ‘die’ and ‘kill’. In Tžuro these work just like ‘break’: the ktuvok does the same thing in both sentences (it dies), so it’s expressed the same way. Traki ‘fall/drop’ works the same way. As English speakers are not used to thinking this way, I’ve marked the ‘special active meaning’, used with the ergative, as (e) in the lexicon.Atej ku štukuliggir .

emperor die.3s>3s ktuvok

The emperor killeda ktuvok .

Kuliggir kaštu .

ktuvok die.3s

The ktuvok died.

Be careful with agentive intransitives like gaj

Atej hustu čelepa.These sentences imply that the emperor finished the book, and that the minister finished entering. (To save space I don’t gloss these verbs as past. If it’s not marked prog, it’s past tense. The gloss >3s on jaddegu clarifies that the agreement is absolutive, not ergative.)

emperor read.3s>3s book

The emperor read a book.

Minnir jaddegu.

minister enter.>3s

The minister entered.

Performatives also use the past, probably because this is the strongest way of stating that an action is complete:

Gojida rut tej.

expel.1s>2s out realm

I expel you from the realm.

Atej husutu čelepa.That is, the action was underway, but there is no assertion that the emperor finished the book. As such this form is used for an action that was underway when another one occurred:

emperor read.prog.3s>3s book

The emperor was reading a book.

AtejIt can also be used for an event that’s not past— that is, it’s happening right now.husutu čelepa nejo minnir jaddegu.

emperor read.prog.3s>3s book when minister enter.3s

The emperor was reading a book when the minister entered.

AtejThis is of course identical to the earlier sentence— it doesn’t tell us that the event is past or present. But context usually tells us. If we’re talking about past events in general, an instance of the progressive is probably also past.husutu čelepa.

emperor read.prog.3s>3s book

The emperor is reading a book.

As an extension of this, you can use it as a near-future promise:

The progressive can also be used as a habitual:Hisitu čelepar kuligi!

read.prog.1s>3s book-that Kulig-gen

I’ll read that damn book!

AtejFinally, the progressive can indicate permission or capability, as in this Baburkunim quote:husutu čelepa jir nemmoro.

emperor read.prog.3s>3s book at morning-pl

In the mornings, the emperor would read a book.

This last usage is rather formal. It probably dates to a time when the modal resources of the language were scant, but it sounds august and reminds people of scripture and law.Vurum avam,jušug arjal,nuvut anint.

watch.prog.3s herdsman / plow.prog.3s farmer / hunt.prog.3s hunter

The herdsman knows herding, the farmer knows plowing, the hunter knows hunting.

Čelepa ŋatej uhusutu.The base is usually the progressive. In CT the past specially marks that the action will be completed, but in the Baburkunim the nuance seems to be that the event is more certain, more abrupt, or done only once. Ability or permission are expressed with the prefix ni; its opposite is pa.

book empress fut-read.prog.3s>3s

The empress will read the book.

Čadimiu nidraud.Obligation, weak or strong, is expressed with jo.

Skourene-pl can-bargain.3p

The Skourenes knew how to negotiate.

Čadimiu pakarauk.

Skourene-pl can’t-fight.3p

The Skourenes didn’t know how to fight.

Anat josiktum.With the modal prefixes, the past is used for statements about the past, the progressive for statements about the future. Compare:

evryone must-tax.>3p

Everyone had to pay taxes.

Čadimiu nidarud.

Skourene-pl can-bargain.prog.3p

The Skourenes know how to negotiate.

Anat josriktum.

evryone must-tax.prog.>3p

Everyone must pay taxes.

Babur šu astir.Though ši can be negated normally (see below), it’s also common to use gohi ‘be wrong’. In this sense, like ši, the progressive serves as the present.

Babur be.3s prophet

Babur was the prophet.

Kurund suč atej.

Kurund be.prog.3s emperor

Kurund is the emperor.

Agiš ši, aneb sič.

thief be.1s / teacher be.prog.1s

I was a thief, (now) I am a cleric.

Berruja sač!

sane-not be.prog.2s

You are insane!

Atej gohu pameraf.

emperor be.3s idiot

The emperor wasn’t an idiot.

Merg girih, ŋečuja sič.

number wrong.prog.1s / free be.prog.1s

I am not a number, I am a free man.

The passive participle works much like our past participle. Tense is indicated by the verb ši ‘be’.

Čelepa hastutu šu.Our present participle implies progressive aspect, but the CT active participle simply makes the sentence active.

book read-pass.part be.3s

The book was read.

Čelepa hastutu suč.

book read-pass.part be.prog.3s

The book is being read.

Aneb hasat šu čelepa.For intransitive verbs, we use the active participle:

teacher read-act.part be.3s book

The cleric read the book.

Aneb hasat suč čelepa.

teacher read-act.part be.prog.3s book

The cleric is reading the book.

Aneb garaj šu/suč.If you put this all together, you’ll see that the participle conjugation is not ergative, but nominative. Experiencers are treated like agents. Also note that the verb (ši) agrees only with the nominative subject; there is no object agreement.

teacher sleep-act.part be.(prog).3s

The cleric was (is) sleeping.

You can use the verbal prefixes with the participles:

Čadimiu nidirad suš.What if you want to use participles but get a progressive meaning? You simply leave out ši:

Skourene-pl can-bargain.act.part be.prog.3p

The Skourenes know how to negotiate.

Atej hasat čelepa, jir minnir jaderag šuč.

emperor read.act.part book when minister enter.act.part be.3s

The emperor was reading a book when the minister entered.

number quantifier adjective possessor noun adjectives PPThus:

If you have have both a number # and a quantifier Q, the meaning is “# of Q nouns”; similar story with a number/quantifier plus the demonstrative.

naraš girl narašur that girl narašli my girl biva naraša some girls an narašar all those girls anebi narašar the teacher’s girls an biva narašar some of those girls biŋ naraša five girls an kuš naraša one of many girls nidiram naraš a beautiful girl naraša nidiram beautiful girls an anebi narašar nidiram all of the teacher’s beautiful girls narašar rut Pelihi those girls from Pelihi ŋok narašar nidiram a nimeraf those two beautiful and smart girls

It’s likely that Tžuro NPs were once consistently head-first, like OS. Derivations are often head-first, like čegan ‘place-all = everywhere’ or sukluj ‘big nose’. Number and quantifiers often follow the noun in the Baburkunim (jeŋu mo ‘one god’); this is rarely done in the Čelepa s Atej except when quoting the Baburkunim. But when that source is quoted daily, its constructions can seem august and even numinous, and they were readily imitated.

With adjectives, some rules emerged:

(I should note that the latter expression is not meant and should not be taken pedantically— it is not a literal claim that every single eŋjippirimi is stylish, any more than saying “birds have feathers” commits one to denying the existence of plucked chickens.)

Šu Kurund akaraka kunum?In the participle paradigm, you front the form of ši. This differs from the conjugated paradigm in that you’re moving an existing verb rather than adding one, and that the form of ši is inflected by person and tense.

be.3s Kurund fighter-pl speak-3s>3p

Did Kurund speak to the soldiers?

Šu gohi?

be.3s err.>1s

Did I err?

Šu aneb hasat šu čelepa?Unsurprisingly, this is also how you question copular sentences:

be.3s teacher read-act.part book

Did the cleric read the book?

Ši hasat čelepa?

be.1s read-act.part book

Did I read the book?

Sač berruja?The answer is saču ‘that is correct’ or gohu ‘that is wrong’.

be.prog.2 sane-not s

Are you insane?

The Baburkunim uses saču rather than šu in asking questions.

A colloquial way to ask a question is to use ye ‘or’:

Kurund akaraka kunum ye?

Kurund fighter-pl speak-3s>3p or

Kurund spoke to the soldiers, right?

Kurund akaraka kunuŋga.If you’re negating a question, note that added šu doesn’t get the -ga, but fronted ši does:

Kurund fighter-pl speak-3s>3p-not

Kurund didn’t speak to the soldiers.

Čelepa hastutu šuga.

book read-pass.part be.3s-not

The book wasn’t read.

Berruja sajga.

sane-not be.prog.2s-not

You are not insane.

Šu Kurund akaraka kunuŋga?Here saču agrees with the negative— indeed, Kurund didn’t speak, the cleric didn’t read the book.

be.3s Kurund fighter-pl speak-3s>3p

Didn’t Kurund speak to the soldiers?

Šuga aneb hasat šu čelepa?

be.3s teacher read-act.part book

Didn’t the cleric read the book?

Negative pronouns do not take -ga:

Čelepali hust lettir!To negate an adjective, use -ja: gač ‘happy’ > gačja ‘unhappy.’

book-1 read-3s nobody

Nobody read my book!

Jatnem degim čelet.

today go->1p nowhere

Today we went nowhere.

If you want to negate an NP, use the modifying pronoun let ‘no’, and don’t negate the verb:

Kutaj kunum let akaraka.

Kurund speak-3s>3p none fighter-pl

Kutaj spoke to no soldiers.

Paran pažih degu rut berruja.You might wonder if this could be interpreted as “A slow man walked…” If the adjective is descriptive, this could happen; but note that the meaning isn’t really different.

male slow walk.>3s from madman

The man walked slowly away from the madman.

However, it’s also possible to turn the adjective into a full argument by adding deg ‘way’. This has the advantage that the new NP can be moved elsewhere in the sentence:

Paran degu rut berruja pažih deg.

male walk.>3s from madman slow way

The man walked slowly away from the madman.

Čralu čadimi tarat jed.An existential proper introduces the subject, so it follows the verb. Before the verb it’s just a locative:

stand-prog.>3s Skourene before door

There’s a Skourene at the door.

Čigum čadimiu čer, hiŋ fsakum.

stand->3p Skourene-pl there / but lack.>3p

There were Skourenes there, but they went away.

Čadimi čralu jiri tarat jed.The same verb can be used as a cleft construction, emphasizing which entity was involved in an action. Note that the former main verb changes to a participle.

Skourene stand-prog.>3s still before door

The Skourene is still standing at the door.

Jippir krurunu amef.This can of course be negated:

God speak-prog.3s>3s soul

Jippir speaks to the soul.> Čralu Jippir kiran amef.

stand-prog.>3s God speaking soul

It’s Jippir that speaks to the soul.

> Čralu amef Jippir kiran.

stand-prog.>3s soul God speaking

It’s the soul that Jippir speaks to.

Čraluga časak Jippir kiran.If you use degi ‘go’ instead of čigi, the implication is that the subject just arrived:

stand-prog.>3s-not penis God speaking

It’s not the penis that Jippir speaks to.

Degu čadimi tarat jed.

go-prog.>3s Skourene before door

A Skourene came to the door.

Fsava nrurunu luj greja.Rather than negating it, you usually substitute fsaki ‘lack’:

clan have-prog.3s>3s big house

The clan owns a large house.

Fsava frusukum holo.The Baburkunim prefers to use existential čigi plus a possessed noun, and this is imitated if you want to sound like the Baburkunim.

clan lack-prog.3s>3p big horse-pl

The clan lacks horses.

Čadimiu čralum imisu, hiŋ teŋe čralu Jippirsu.Literally: The Skourenes, their cities exist; but you, your God exists.

Skourene-pl stand.prog.>3p city-pl-3 / but you-pl stand-prog.>3s God-3

The Skourenes have cities, but you have Jippir.

Recall that the thing existing is in the absolutive— there is really no semantic role left for the possessor, so it’s just stated as a topic, and isn’t marked on the verb.

Possession within an NP (X’s Y) is indicated two ways: Y si X, or X-gen Y. Si > s before a vowel.

hol s atejThe si form must be used if the NP is more than two words.

horse of emperor

the emperor’s horse

ateji hol

emperor-gen horse

the emperor’s horse

hol s atejli zal a jeŋusarak jat JippirimIf the possessor is a pronoun, use the pronominal forms instead: holsu ‘his horse’, atejli ‘my emperor’.

horse of emperor-1 mighty and god-loving in Jippirim

the horse of our mighty and pious emperor in Jippirim

Atej čelepasur apiči brujum.If the giftee is omitted, the gift is promoted to direct object:

emperor book-3-this follower-pl give.past-3s>3p

The emperor gave this book to his followers.

Patali braji. Ižraŋala brija.

year-pl-1 give.past-2s>1s / honor-2 give.past-1s>2s

You gave me life. I gave you honor.

An pat biriju kuš biga.Verbs of permission like nisaji ‘allow’ work the same way. p>Valati ‘name’ simply throws in the name as an argument, without any verb marking or agreement.

every year give.prog-1s>3s much coin

Every year I give away much money.

Atredesu sadat valautu Jippirprurundis.For speaking, note the distinction between kini ‘speak to somone’ and mali ‘speak things’. If you really need all three arguments, use kini plus the instrumental tot.

parent-pl-3 boy name-3p>3s Jippir-bless.prog.3s>1d

His parents named the boy Jippir-blesses-us.

Valiriti Anint.

name-prog-1s.refl hunter

I am called Anint.

Jippir kunim. Isača mulu.

Jippir speak-3s>1p / truth speak-3s>3s

Jippir spoke to us. He spoke the truth.

Jippir kunim tot isača.

Jippir speak-3s>1p using truth

Jippir spoke the truth to us.

As in English, the first three can be used to join any constituents: Janei a Helu ‘Janei and Helu’; zal hiŋ pameraf ‘mighty but stupid’, jat jala ye jat čal ‘in the rivers or in the sea’.

am and (before a consonant, a) ye or hiŋ but zun therefore kor because ret then, next taj besides, in addition yana moreover, even more so soga except, unless jo relativizer; explained below

Jippir mul am asti.It’s common, though a bit formal, to include the conjunction between each conjoint: Dusilim a Jippirim a Pajimi.

Jippir speak-3s and hear-1s

Jippir spoke and I listened/obeyed.

Kor ‘because’ and taj ‘besides’ can also be prepositions (kor ikaštasu ‘because of his death’).

In the following conjoined sentences, who left?

Ŋamaššu atej mulu ret sevu.The case roles win: the same person is assumed to take the absolutive role in both sentences, so sevu here means the wife left.

wife-3m emperor speak-3s>3s and leave-3s

The emperor spoke to his wife, then ?? left.

If you want the emperor to leave, the first sentence can be placed in the antipassive, which places the emperor in the absolutive:

Atej omalu tot ŋamaššu ret sevu.

emperor antipass-speak-3s with wife-3m and leave-3s

The emperor spoke to his wife, then he left.

OS has no prepositions, and it’s worth noting that all of these derive from something else: e.g. jat < jadi ‘be inside’; tot < tor+t ‘with the hand’.

duki on top of in compared to jat in, inside; to, toward jir at (a time) kor because of min under, below pit after (in time), since rut out of, outside; from (a place) si of (before a vowel, s) taj next to, near, alongside, with (accompanying) tarat in front of teŋ above, over tot using, with (instrumental) tret before (in time), until yav for, because of, in order to

In the Baburkunim, the genitive is often used as a locative: imi ‘in the city’, savai ‘in the mountains’, čali ‘at sea’. This is archaic, but again you can’t go wrong borrowing from that book.

Kaštu a yetuja ava?An expression like Amin kuštu ava? is ambiguous between Who did the servant kill and Who killed the servant? Context will usually make this clear; if not, recall that an ergative-absolutive sentence can be split into two sentences:

die.3s and crown.3s>2s who

Who died and made you emperor?

Čralu kešp avali?

stand-prog.>3s spittoon where

Where is the spittoon?

Babur ŋullaur mulum avar?

Babur word-pl-that speak-3s>3p why

Why did Babur speak these words?

Amin kaštu; kušt ava?The interrogatives are not used for relative clauses, as explained below.

servant die.>3s / die.3s who

The servant died— who killed him?

Amin kušt; kaštu ava?

servant die.3s / die.>3s who

The servant killed someone— who was it?

Minnir iruruvu kišan atej.The absolutive argument jumps to the auxiliary. That is: yevi ‘want’ normally agrees with the wanter (ergative) and the thing wanted (absolutive); but here the absolutive agreement is with the person spoken to, borrowed from kisan ‘speaking’. To reinforce this, note

minister wish-prog-3s>3s speaking emperor

The minister wants to speak to the emperor.

Minnir iruruvi kišan.Normally iruruvi would be ‘he wants me’!

minister wish-prog-3s>1s speaking

The minister wants to speak to me.

If there’s no absolutive argument, use the passive participle instead:

Mroraŋa.

fear-prog-2s

You are afraid.

> Grorahu moŋugu.

wrong-prog-2s fear-pass.part

You are wrong to be afraid.

Atej hustu čelepa.If you want to make the book the focus, or if you want to keep the emperor in the sentence, you simply front it:

emperor read.3s>3s book

The emperor read a book.

> Hastu čelepa.

read.>3s book

The book was read.

Čelepa hustu atej.(See the Sentence order section for more on where arguments go and why.) The antipassive (the prefix o-) changes the absolutive argument to an ergative, and demotes the former absolutive argument if any to a prepositional phrase:

book read.3s>3s emperor

The book was read by the emperor.

Atej okaštu tot amin.On its own, the effect is a demotion of the actor’s agency— it was something happening to him, or perhaps it was done absently or accidentally. The translation above is too direct; the pragmatic effect is like The emperor by his actions allowed the servant to die.

emperor antipass-kill.>3s with servant

The emperor killed a servant.

But it’s also useful in conjunctions, as it allows the subject of both sentences to be the same:

Atej omalu tot amin, ret ŋalsu.Without the antipassive it would be the servant who ate the dinner.

emperor antipass-speak.>3s with servnt then dine.>3s

The emperor talked to a servant, then ate dinner.

The causative (the prefix ye-) raises the valence. With intransitives, the causative simply adds a new ergative argument, the causer:

With transitives, the former ergative becomes an absolutive, and the former absolute simply floats in the sentence without verb agreement.

Gaji.

sleep.>1s

I slept.

> Ažanak yeguji.

magician caus-sleep.3s>1s

The magician made me sleep.

Because yedumi does not mark the person loved at all, an explicit pronoun teŋ must be used. Compare:

Dima.

sleep.1s>2s

I loved you.> Ažanak yedumi teŋ.

magician caus-love.3s>1s 2s

The magician made me love you.

Atej yekuštu minnirsu amin.Since case is not marked on the verb, the above sentence could technically also be The emperor made the servant kill his minister. But the more active argument is usually placed closer to the verb.

emperor antipass-kill.3s>3s minister-3m servant

The emperor made his minister kill the servant.

For adjectives, the derived form is transitive. Compare the absolutive yešaju ‘it became red’with the ergative yešuju ‘he/she made it red’.

Atej kaštu minnir, jo goduršu.A jo clause in effect modifies the entire sentence, not an NP. The first sentence could therefore also be interpreted The emperor who betrayed him killed the minister. This could be handled by our old friend context; but also by the general rule that you attach a jo clause to the closest NP. So the traitorous emperor would have to be expressed thus:

emperor kill.3s>3s minister / sub betray.3s>3s

The emperor killed the minister who betrayed him.

Hast čelepar, jo patali yeguku.

read book-that / sub life-1 change-3s>3s

Read this book, which changed my life.

Degu nem, jo fsiku anat.

go->3s day / sub lack.1s>3s all

There came the day when I lost everything.

Minnir kaštu atej, jo goduršu.Or even this, though this is rather literary:

minister kill.3s>3s emperor / sub betray.3s>3s

The minister was killed by the emperor who betrayed him.

Jo goduršu, atej kaštu minnir.You can also skip over NPs that don’t make sense semantically:

sub betray.3s>3s / emperor kill.3s>3s minister

The emperor, who betrayed him, killed the minister.

Atej hustu Baburkunim, jo sukum čelepau.A non-restrictive clause must be marked explicitly. The easiest way is to add another conjunction:

emperor read.3s>3s Baburkunim / sub like-3s>3s book-pl

The emperor who loved books read the Baburkunim.

Paranur yedumi teŋ, a jo suč ažanak.Or you can use the conjunction taj ‘besides’:

man-that caus-love.3s>1s 2s, and sub be.prog.3s magician

That man, who is a magician, made me love you.

Aŋat nuŋgi, taj šu čadimi.

trader cheat-3s>1s / besides be.3s Skourene

I was cheated by the trader, who was a Skourene.

Čralum kuš jeŋum. So guruh.In the Baburkunim, reported speech works this way, though there is an orthographic way of marking it:

stand-prog->3p many god-pl / 3s false-prog-3s

There are many gods. (This is) false.

—Čralu mo jeŋu; zal sič— Jippir mul.In CT you keep the sentential argument as it is, and use the participle paradigm for the main clause:

stand-prog->3s one god / I be.prog.1s / Jippir say.3s

“There is one god; I am he,” said Jippir.

Čralum kuš jeŋum gorah suč.You can back the sentential argument, but then you must use the conjunction jo.

stand-prog->3p many god-pl false-act.part be.prog.3s

It’s not true that there are many gods.

Gorah suč, jo čralum kuš jeŋum.In popular speech you could simplify further:

false-act.part be.prog.3s sub stand-prog->3p many god-pl

It’s not true that there are many gods.

Gorah čralum kuš jeŋum.The CT grammarians warn against this, but it was predominant by 3000 at least.

false-act.part stand-prog->3p many god-pl

It’s not true that there are many gods.

Many time and place expressions are prepositional phrases. CT, like OS, does not use the TIME IS SPACE metaphor for these, but uses separate prepositions for time and space.

Fronting the expression, as in English, topicalizes it.

Udregim jat Pajimi jir sakluj.Unlike English, you can’t omit the preposition:

fut-walk.prog.>1p in Pajimi during winter

We will go to Pajimi in the winter.

Jir sakluj Udregim jat Pajimi.

during winter fut-walk.prog.>1p in Pajimi

In the winter, we will go to Pajimi.

Jat Pajimi udregim jir sakluj.

in Pajimi fut-walk.prog.>1p at winter

As for Pajimi, we will go there in the winter.

Jir atenluju pačragim jat Jippirim.You can use a place or time word as an anchor for a relative clause:

during summer-pl live.prog.>1p in Jippirim

Summers, we live in Jippirim.

Deguga nem, jo sdati rut karak.That was all Babur had to work with, but after him nem jo > nejo ‘when’, čeg jo > čeŋo ‘where’. These are subordinators, not interrogatives.

go->3s-not day / sub run.prog.1s out fight

This is not the day when I run from a fight.

Fsava ufsaku nejo ukšati.

clan fut-die.prog.>3s when fut-die.prog.>1s

The clan will fail when I die.

Čralu jeŋali čeŋo Babur jaku.

stand-prog.>3s shrine where Babur born.>3s

There is a shrine where Babur was born.

Uhasatu čelepar, ujnasa.More formally, you can use the construction jo X, ret Y. (This looks like a relative clause, and historically it was one. However, it need not refer to any argument in the consequence.)

fut-read.prog.2s>3s book-that / fut-rich.prog.>2s

If you read this book, you’ll get rich.

Jo kačar kanju, ret nrarinu.CT has no irrealis, nor the sort of tense changing that happens in English conditionals. You use the same tenses you’d used in declarative statements (cf. Kačar kanju ‘you hid the gold’, Nrarinu ‘we have it’.)

sub gold hide-2s>3s / then possess.prog.1p>3s

If you had hidden the gold, we would still have it.

Jo srača, ret kšatim.

sub right-prog.>2s / then die-prog.>1p

If you are right, we will die.

Jo jeja sčuju, ret jogosrotu.

sub person sin-prog.>3s / then must-expiate-prog.>3s

If a person sins, they must make expiation.

If you’re not contemplating a counterfactual or a future possibility, but stating a logical connection, you can use the construction Nejo X, zun Y (that is, “when X, then Y”).

Nejo tašla suč toš, zun sač čailan.

when skin-2 be.prog.3s blue / therefore be.prog.2s iliu

If your skin is blue, you are an iliu.

Atej prurujum meddejjiri in koriŋ.If instead you use ten ‘above’ or min ‘under’, you have a comparative:

emperor defeat-prog.3s>3p enemey-pl like lion

The emperor defeats his enemies like a lion.

Girekur suč mineraf in žoh.

pig-that be.prog.3s smart like dog

This pig is as smart as a dog.

Johli suč mineraf teŋ žoh.There is no superlative, though you can express the idea by using an ‘all’ in the comparison class:

brother-1 be.prog.3s smart over dog

My brother is smarter than a dog.

Johli mineraf min zeŋke.

brother-1 be.prog.3s smart under bear

My brother isn’t as smart as a bear.

Metli suč nidiram teŋ an naraša.These constructions do not give you an adjective that can be used as a simple modifier, like ‘smarter’. But the augmentative -luj is often used in the same way: nakluj ‘very new’ often means ‘newer’; balarluj is often ‘better’.

sister-1 be.prog.3s beautiful over all girl-pl

My sister is more beautiful than all (other) girls.

It was once common to form names using a conjugated verb or even a whole sentence:

In early times, people usually went by one name. If that wasn’t enough, you could be identified by the name of your fsava (Jarah si Jalluj), or your town (Holit Jandimi), or even a nickname (Lonti Morit).

Pundis he (God) blessed us two Upuruj he/she will conquer Yepuču he (God) strengthened him/her Ujunus he/she will be rich Atejnuruj the emperor knows Babursut he/she obeys Babur Tajjaburuš he/she travels far

In modern Šura, these have developed into family names. See the Šureni grammar for how modern families (sigrejau) relate to the fsavau.

By the time of CT, titles had reappeared, but were supposed to be limited to a single word: e.g. asev ‘head of the clan’, ŋajjos ‘queen’, atej ‘emperor’, aneb ‘cleric’, teŋŋir ‘saint’. That is, you can call the emperor Barutra or atej, but not both at once. There were no terms like ‘your majesty’.

Later yet you could add a title to a name: Barutra atej, Janei ŋajjos, Ajažril aneb, Fisei teŋŋir. It was still considered tacky to add more (e.g. the name of their fsava or their realm, or words of praise).

Only in modern times can you add a title to an individual + family name, and only on first reference. Thus if Agrid Jideburi becomes Trustee, he is called Agrid Jideburi ažraŋ.

This structure reflects a world where women stay at home while men roam widely to take care of herds, hunt, go on raids, or trade with the settled states. The men were simply not at home much of the time. This in turn meant:

To put it another way, the clan was structured not on the husband-wife bond, but the brother-sister bond.

A fsava kept horses, cattle, and sheep or goats. To keep from overgrazing, these were grazed in smaller groups: the base camp was generally where the largest group of cattle was, and the women stayed there. Some fsavau grew crops, and naturally stayed by the fields. But even these moved after a year— if nothing else, this cut down on cleaning.

Daughters stayed with their fsava, slowly rising in prestige as she had children. She could be considered an elder once she had daughters, as she had contributed to preserving the fsava into the next generation.

Sons had a more complicated life. To win a bride, they had to win not only her support but her fsava’s; this usually meant spending a year or more living with and working for her clan. After the marriage, he could spend his camp time either in his own or his wife’s fsava and usually spent time in both, The leaders of the clan were male— all brothers of one of the female members. The highest authority was the oldest male, the asev. The eldest female, the ŋasev, was in charge when the asev was absent, and was not to be crossed lightly even if he wasn’t.

The animals, except for horses, belonged to the clan and stayed with it. An individual, male or female, owned several horses. These, and treasures like gold or weapons, were inherited not by a man’s children but by his sister’s.

Young men had little authority or property, and spent most of their camp time with their wife. As he grew older, however, a man spent more time in his own fsava. He could hunt with his wife’s clan, but raid only with his own. (If a clan was lacking in males, it might adopt one. This was often a son-in-law, but the actual adoption was as brother or nephew to an elder female.)

The most important kinship terms were these. The order is important: within each generation group, a person gets the highest possible name. E.g. the same person might be your sovei ‘elder’ and ŋasev ‘aunt’, but you would use the highest-ranked term for her, ŋasev.

For ego’s generation and those following, the suffixes -luj and -it could be used to indicate relative age. E.g. metluj is an older sister, metit a younger one.

asev the eldest male in the fsava, the ultimate decision maker ŋasev the eldest female maran mother aŋesum mother’s husband sovei aunt— any female in the previous generation or before nujat uncle— any male in the previous generation or before met sister joh brother tajei cousin— anyone else in your own generation fsevvu heir— prototypically your eldest sister’s eldest son mori niece— any sister’s daughter meti nephew— any sister’s son sadat son maral daughter tajjeg anyone else (child of a tajei)

This system of course belongs to the nomadic past. It fits the world of the Baburkunim, but after the conquest few Tžuro lived as herdsmen— all the more so once the conquered Skourenes adopted Jippirasti and learned Tžuro. Clans grew smaller and came to resemble the Skourene bsepa; increasingly couples lived together, apart from either fsava; city goods were inherited by children. Nonetheless the kinship terms, and thinking about families in general, were still based on the nomadic system.

One consequence: ‘love’ is divided between feelings for one’s wife or sex parter (idima) and those for one’s family (ipanda). Love between humans and God is ipanda, not idima… though the Fanpita was known (and somewhat disparaged) for using the language of adima with God.

One of the more charming corollaries is biviti, a holiday devoted to the brother-sister bond. Even today, brothers and sisters visit and exchange small gifts.

Imagine this scenario: A group of men, tired and hungry from a long day’s riding, come to the camp of a fsava, currently occupied only by women and old men. This was a fraught moment, if they did not know each other; if all went well, it was an opportunity for dinner, companionship, and possibly sex. But a visit was not always welcome, if the men were rivals to the fsava, or were impolite, or if the camp was low on food. If it came to it, the women were expert archers and horse riders themselves, and could easily chase the tired men off. On the other hand, nomadic life depended on such exchanges, and hospitality was a virtue. The introductory exchange might go like this:

Balar: Kor Jippiri iyeva, istikig degi, taj biva joholi, jat lonalila palati a lonti.At this point the ŋasev will indeed bring refreshments, and the conversation will continue, mostly mutual probing to see if the clans have any relations or common friends, however remote, what trade goods each side possesses, and what news the travelers bring.

because Jippir-gen desire / insignificant walk.1s / alongside few brother-pl-1 / in oasis-2 kindness-gen and peace-gen

Balar: By Jippir’s will, I have arrived, insignificant, with my few brothers, to your oasis of kindness and peace.

Valatli suč Balar, nujudja fsavali suč Holičal; yiriv modeg lon.

name-1 be.prog-3s / unknown clan-1 be.prog-3s Holičal / want.prog.1s only water

My name is Balar; my unfamed clan is Holičal; I desire only water.

Tihilon: Jippir pundim tot ibišala jim a gačterad.

Jippir bless.3s>1p using journey-2 long and good-omen

Tihilon: Jippir blessed us with your long and fortunate journey.

Nraronum ŋanak am ijiŋa a gej, kor šuga abiši kaŋ suč lami?

have.prog.2p>3p wine and food and bed / because be.3s-not visitor-gen foot be.prog.3s godling-gen

You will have wine, and meat, and a bed, for is not the foot of a visitor the foot of a godling?

Valatli suč Tihilon; fsavali čuk suč Nirššu. Avank asevi žono ubralug kor fasakla, hiŋ gač jo sraroku ivankala.

name-1 be.prog.3s Tihilon / clan-1 barren be.prog.3s Nirššu / Avank uncle-gen bone-pl fut-hurt.prog.>3p because absence-2 / but happy sub enjoy-2p>3s stay-2

My name is Tihilon; our miserable clan is the Nirššu. Our leader Avank will regret missing you, but will be happy if your stay was pleasant.

Before the Tej, the early mention of Jippir was itself a sign of peace, as Jippirasti was supposed to unite the Tžuro and forbid all wars and raids between fsavau. Non-Jippirasti would instead mention their own gods (each clan had one male and one female god).

Here, as usually, each side refers to itself with extreme humility and to the other with great praise. It was unwise to take these poses too seriously. Other approaches were possible: e.g. a group of men could come in with boasting and braggadocio. This was risky, but could be pulled off with a certain jocular playfulness. It often meant that the visitors had had a successful hunt, thus meat to share.

In the worst case— before the Jippirasti truce— a group of raiders had already vanquished the clan’s warriors. The encounter would be extremely polite and businesslike: proofs would be required, and straggling survivors given time to return. Both sides would exchange presents. Sex was off the table, since widows normally abstained for six months, and it was not yet known which women were widows. Naturally urban customs differed; they were a mixture of Tžuro and Skourene traditions. They are better described in the grammar of Šureni.

hol horse eŋgal mare, adult female horse, not yet bred kirz mare, adult female horse who has been bred holit foal, young male horse mosto filly, young female horse sanit yearling ačasak stallion, uncastrated male horse tensu gelding, castrated herd animal pabakas wild, untamed horse buka clan’s sacred horse, ridden once a year by the asev jinjapa a very fine quality horse šundo a mediocre or disappointing horse soŋka a stout horse, suitable for heavy riders but not for war kodali an old or worn-out horse huval reddish-brown (these color terms are used only for horses) yehi creamy or golden naj dull yellow mulk black or deep brown šaj maroon talka speckled sarak blaze, a stripe on the face majint starry mark on the face taraj sock, lighter color on the lower leg ferd saddle makaš saddlebag hina saddle cloth čarag stirrup taraš bridle dusi reins nerm lasso neče spurs japa mane vauka tail (of horse only) kruŋ hoof sukmin fetlock, protuberant part just above hoof degi walk (slowest gait) goropi trot sati canter nefti gallop (fastest gait) kui command to turn right hau command to turn left žegi startle at something (while being ridden) dokodi balk, be stubborn, refuse to obey nehehi neigh yendi break, accustom an untrained horse to handling keri train a horse (dressage) dibi charge— run towards an enemy čam slack, loose reins kušpi fire arrows while retreating turuk special arrow for shooting an enemy’s horse ativa stable roma mare’s milk zai kumiss, fermented mare’s milk čočo horse manure yesa horse blood (esp. as an emergency drink) teš mange (lit. ‘leather’, as the disease cause hair loss)

The standard edition of the Baburkunim dates to 1810. The book theoretically defines CT and LŠ, but contains multiple archaisms… yet these are so familiar to Jippirasutum that they are available in formal registers. Think of 19th century writers who imitate the KJV when they want a tone of august or antique solemnity. At the same time writers at least till the 3500s convinced themselves that they were not merely influenced by the Baburkunim but writing in the exact same way. This is not really true of CT and even less so of LŠ.

At the same time the text is relatively simple, often epigrammatic. This was a point of pride for believers, who considered that all other religions were full of additions (ijeba) and confusion (igalna) added by humans, causing Jippir to speak to Babur “clearly and thoroughly” (nijištu a teŋku). The book is divided into 71 asutum ‘speeches’; this text is from number 17, concerned with issues of competing authorities. For the original audience, the problem was acute, as the clan might not have converted to Jippirasti.

This passage relies heavily on the kinship terms defined above.

It refers to the atej, but there was no atej until Kurund, in 1593. However, Babur referred frequently to the tej, the unified realm that Jippirasti would bestow on all the Tžuro. It was natural to imagine an atej in charge. It’s also possible that the text was altered once the atej existed. (The atej could speak for Jippir, and if anyone could alter the words of the Baburkunim it was Kurund.)

Krušuna maranla, šaču saratga? Yana krušuna asevla? Yana krušuna lam? Yana krušuna jeŋu? Usrarati.Asti means both ‘hear’ and ‘obey’.

speak-prog-3s>2s mother-2 / stand.>3s listen-prog-3s-not / more.so speak-prog-3s>2s uncle-2 / more.so speak-prog-3s>2s angel / more.so speak-prog-3s>2s god / fut-listen-2s>1s

When your mother speaks, do you not listen and obey? How much more if your uncle speaks? How much more if a lam speaks? How much more if God speaks? Hear and obey Me.

Atej sučus fsevvuli and manli yetiju. Usraratu, soga ŋullausu gomruruli.The core of something is its žono ‘bones’; its vigor or potency is its šaj ‘blood’. These might be ‘heart’ / ‘guts’ in English. When contrasted with žono, mej ‘body’ means ‘flesh’, what fills the thing out and what is visible to others.

emperor stand.prog.3s heir-1 and people-1 caus-rule.1s>3s / fut-listen-2s>3s / except word-pl-3 deny.prog.3s>1s

The atej is My nephew and I have placed him to rule My people; obey him, unless his words go against Mine.Nujatala a johlujula sačus fsavai žono. Usraratum, soga ŋullausu gomrurulim zal ye atej.

uncle-pl-2 and brother-big-pl-2 stand.prog.3p clan-gen bone-pl / fut-listen-2s>3p / except word-pl-3 deny.prog.3s>1p I or atej

Your uncles and your elder brothers are the spirit of your fsava; obey them, unless their words go against Mine or the atej’s.

Fsavala gožraruŋum moŋi am ikulkina a čraytafat; nujataisono ješe gosruduka.It’s so common for the Baburkunim to give lists of three things that commentators noticed and gave additional rules, noting that such a list should not be taken as exhaustive, but also if three items were given, they each must refer to different things. The last word shows dual agreement, as the object is (pairs of) eyes.

clan-2 dishonor-prog.3p>3s fear and lies and arrogance / male.elder-pl-gen-3p eye-pl dismay-prog-2s>3d

Cowardice, falseness, and arrogance dishonor your fsava and disappoints your elders’ eyes.

Fsavaila mej sačus maranla am metela am soveimla. Usraratum, soga ŋullausu gomrurulim zal ye atej ye nujatala.In CT these would be prepositional phrasess jat X.

clan-gen-2 body stand.prog.3p mother-2 and sister-pl-2 and aunt-pl-2 / fut-listen-2s>3p / except word-pl-3 deny.prog.3s>3p of me or atej or uncle-pl-2

Your mothers, your sisters, and your aunt’s daughters are the body of your fsava; hear and obey them, unless their words go against Mine, or the atej’s, or your elders’.

Maranla gožraruŋum pašanakat am igiša a paljat, jo yejuka baŋag

mother dishonor-prog.3p>3s idleness and theft and viciousness / sub bear.3s>2s hurting

Idleness, theft, and viciousness dishonor the mother who in pain bore you.

Šajla gožraruŋu, čukati ye karkigati ye igišai sučus metela.

blood-2 dishonor-prog.3s>3s poverty-gen or violence-gen or theft-gen stand.prog.3p sister-pl-2

To leave your sisters to poverty, violence, or theft dishonors your blood.

Ijiŋala braju ŋamašla a geji yedagu; gožraruŋum paljat ye istuja ye ikanjudimi, am teŋ a fsavala uyebzaŋu moŋkosuŋ.Gej is both tent and bed, so inviting you there implies sex. “To harm the ears” is an idiom for eliciting disdain.

food-2 give-3s>2s wife-2 / and tent-gen invite-3s>2s / dishonor-prog-3p>3s rudeness or uncleanness or illicit.sex / and you and clan-2 fut-hurt.prog.3d>3p ear-pl-3sf

Your wife gave you food, and took you into her tent; to be rude, unclean, or sexually indecent dishonors her, and will make you and your fsava an evil noise in her ears.

Valatli sučus Jippir. Jo upiča so mala a pičaga, ret legdi čig papiti.

name-1 stand.prog.3s demanding-one / sub fut-follow-1s>2s 3s say-2s and follow-prog-2s-not / then first stand pagan

My name is Demanding. If you say you will follow, and you do not, it were better that you remain a pagan.

Clerics sifted through the Baburkunim— addressed to steppe nomads— to provide a principled basis for ruling an urban civilization based on trade and agriculture. This process was rocky, and impeded by the decline of the Kurundasti.

When the more vigorous and less fundamentalist Anajati came to power (2375), it was time to codify the consensus, and settle any remaining disputes. The result was the Čelepa s Atej (Book of the Emperor), completed in 2391, under the second atej, Gotandi. As its preface modestly tells us, the atej wished to “settle all uncertainies for all time.”

The book is four times longer than the Baburkunim, and far drier; it’s organized into 1,243 yaumalau ‘questions’. Almost always these begin with a quotation from the Baburkunim and pose one or more questions of interpretation. Often various authorities are quoted, then a final decisive answer from the emperor, who was also the ultimate religious authority. (The book makes it sound like these authorities were talking to each other, but this is an editorial illusion— they are quotations from the previous five hundred years of moral disputation.)

This raised the question, what is the status of the rejected answers? This had to be answered by later writings: they are authoritative only when they do not contradict the emperor’s answer; even when they do, they are valuable for providing context and pointing out naïve errors.

The book is foundational to the Sačutu (Orthodox) and Fanpita (Feidal) pitau— the Tžuro-speaking ones. It and other Anajati writings define proper Classical Tžuro, more so than the Baburkunim itself (almost 600 years old by this point).

—Igejruda suč stuja.— Jippir mul am asti.Even a minimal quotation from the Baburkunim is followed by the statement Jippir mul am asti. As in the first sample text, asti refers to hearing but implies obedience.

rape be.prog.3s unclean / Jippir speak.3s and hear-1s

Babur told us, rape is sin. Jippir spoke and I obeyed.

Ŋullar prušupu gej, hiŋ an anebe šarup, greja jrišatu gej.The previous sentence exemplifies the old form of reported speech, used in the Baburkunim (and still used to report dialogs). This one exemplifes the CT way, using the participle paradigm.

word-that mark-prog-3s>3s / but all cleric-pl agree-prog-3p / house see.prog.>3s tent

This word refers to the tent, but all clerics agree that a house is considered a tent.

Mefajag mul, stuja suč adima rut gej, mot pašriripu jat daldeg, ye jat gokkiri greja.This passage should be read carefully with respect to argument order, as it demonstrates how often it’s topic-first. We’re talking about the man, so he comes first, and the possible speakers last. Kunu agrees only with the first conjoint. But if two or more third-person referents are conjoined, the verb is plural.

Mefajag speak.3s / unclean be.prog.3s sex outside tent / one.thing point.prog.1s>3s in garden / or in other.one-gen house

Mefajag said, it is sin to make love outside the tent, for instance, in a garden, or in someone else’s house.

Namauni mul, nisagu, soga nujatuga mirjat, kor tžekat suč stuja čeŋo nijišatu.

Namauni speak.3s / allow.prog.>3s / unless know.prog.>3s-not privacy / because nudity be.prog.3s unclean when can-see.prog.>3s

Namauni said, this is allowed, unless privacy is not assured, because nudity is sin when it can be seen.

Ipanda mul, žono si gej suč inisaja, kor suč ijora si ŋamaš. Zun ŋamaš šurup, čraluga istuja.

Ipanda speak.3s / bone-pl of tent be.prog.3s permission / because be.prog.3s domain of woman / therefore woman agree.prog.3s / stand-prog.>3s-not sin

Ipanda said, the essence of a tent is permission, because it is the domain of the woman. Therefore there is no sin if the woman consents.

Atej mul, malulu sruruju inisaja, hiŋ Jippir iruruvu yejeraŋ ŋamaš; a soŋ yejruruŋu gejsuŋ, jo suč ijorasuŋ.

emperor speak.3s / text touch.prog.3s>3s permission / but wish-prog-3s>3s sanctifying woman /and she sanctify-prog-3s>3s tent-3sf / sub be-prog.3s domain-3sf

The emperor says, the text is about permission, but also the intent of Jippir is to make the woman sacred, and she makes her tent sacred, it is her domain.

Yezulis mul, nimurul paran, yedigu, hiŋ ŋamaš murul, yedugiga. Isača nrurunu ava?

Yezulis speak.3s / can-say.prog.3s male / invite-3s>1s / but woman say.porg.3s / invite-1s>3s-not/ truth have.prog.3s>3s who

Yezulis said, a man may say he was invited, but the woman says he was not invited. Who is right?

Avam mul, jo sajuga jat gej, ret nijištu suč igejruda. Jo saju jat gej, šu yeduguga?

Avam speak.3s / sub act-3s-not in tent / then clear be.prog.3s rape / sub act-3s in tent / be.3s invite-3s>3s-not

Avam said, if the act did not occur in a tent, it is clearly rape. If it was in a tent, did she not invite him in?

Ugačim mul, jo paran karkig jaddugu gej, yedeguga a gokšatu.

Ugačim speak.3s / sub male violent enter.3s>3s tent / invite.>3s-not and must-kill->3s

Ugačim said, if a man forced his way into a tent, he was not invited and he must be executed.

Atej mul, Fsavaila mej sačus maranla am metela am soveimla. Usraratum, soga ŋullausu gomrurulim zal ye atej ye nujatala. Jippir mul am asti.

This is a quotation from the previous sample text; see the gloss there.

The emperor says, Your mothers, your sisters, and your aunt’s daughters are the body of your fsava; hear and obey them, unless their words go against Mine, or the atej’s, or your elders’. Jippir spoke and I obeyed.

Šu paran kunu Jippir ye zal ye nujata, deg jat gejsuŋ? Gohu, pič ŋullar si ŋamaš.

be.3s male address-3s>3s Jippir or I or elder-pl / go in tent-3sf / wrong.>3s / follow word-pl of woman

Did Jippir, or myself, or the elders tell the man to go into her tent? No, believe the words of the woman.

I’ve removed some lines to keep the text manageable. Aneb Majaŋi would not want you to think he had not addressed many pedantic objections. In a scholarly work, of course, he would have considered the question in far more detail, with scholarly citations all at least 500 years old.

The most striking grammatical difference here is the greater use of the participle paradigm.

Atej suč ava, nejo atej čraluga?The parenthetical is an old legal maxim and thus uses the conjugation paradigm. The major entrustable powers are judge, general, and legislator.

emperor be.prog.3s who / when emperor stand-prog.>3s-not

Who is the emperor, when there is no emperor?

Yaumalar suč ništig tarat an Jippirasutum, kor ŋok yara. (Gok nideraga atej nrurunum, hiŋ nižraraŋum.)

question-this be.prog.3s important in.front all Jippir-ist-pl, because.of two reason-pl / other power-pl emperor have-prog-3s>3p / but can-entrust-.>3p

This question is important for all followers of Jippirasti, for two reasons. (The emperor has other powers, but those can be delegated.)

Ništi, atej suč itikiluj adep teŋ igošapau si jeŋu, soga gomaral suč jeŋui ŋullar, ŋullausu suč itiki.This is a quotation from the first sample text; see the gloss there. It’s now accepted to abbreviate Jippir mul am asti.

first / emperor be.prog.3s final-big judge over dispute-pl of divinity / except denying be.prog.3s god-gen word-pl, word-3sm be.prog.3s final

First, the emperor is the ultimate judge over religious disputes. Unless he contradicts scripture, his word is final.

Lešpi, saččeg si ijora fasav suč atej.

second / authority of government descending be.prog.3s emperor

Second, the authority of the government derives from that of the emperor.

Nujatala a johlujula sačus fsavai žono. Usraratum, soga ŋullausu gomrurulim zal ye atej. JM&A.

Your uncles and your elder brothers are the spirit of your fsava; obey them, unless their words go against Mine or the atej’s. JM&A.

Atej fasak, šu modeg Jippir a nujata sat josiš?The first phrase would be Atej fasak šuč in proper CT, unless the aspect was emphasized: “if the emperor just disappeared.” But in LŠ omitting suč forms an adverbial: “the emperor being gone…”

emperor lacked / be.3s only Jippir and uncle-pl obeying must-be-prog-1p

In the absence of the emperor, are only Jippir and clan leaders to be obeyed?

Gomeraf suč; jatnemi ijora niran josuč saččeg teŋ man, yana nejo jat tappa man derap suč ijora jo sarak sono.in is used as in comparatives: ‘two, compared to three’. Stacked quantifiers X Y are interpreted X of Y, thus ‘two-of-three of all teachers’.

absurd be.prog.3s / modern government having must-be-prog-3sauthority over people / moreover when in democracy people choosing be.prog.3s government / sub pleasing them

That is absurd; a modern state must have authority over the people— even if, as in a democracy, the people choose the government that pleases them.

Yana gomeraf, nejo Jippiri man niran suš kuš teje, hiŋ mot valat suč atej.

also absurd / when God-gen people having be.prog.3p many realm-pl / but one.thing naming be.prog.3s emperor

It is also absurd when the people of God have multiple realms, yet one of them calls itself an emperor.

Jarap jat Sačutu suč, ajjos pašap suč atej jat saččeg hiŋ lettir jat jeŋu.

rule in Sačutu be.prog.3s / king pointing be.prog.3s emperor in authority but nothing in religion

The ruling in Sačutu is that the king stands for the emperor in authority, but not in religion.

Čraluga minan jat jarapa ye jat isota yav igomala si saččeg si ijora, kor čraluga atej.

stand-prog.3s-not foundation in rule-pl or in morality for denial of authority of government / because stand-prog.>3s-not emperor

There is no basis in law or morality for anyone to deny the authority of the government, on the basis that there is no emperor.

Čraluga ajjos jat Šura; šu atej ye ažraŋ ye andraga mafali ye jurudeg man?

stand-prog.3s-not king in Šura / be.3s emperor trustee or whole Senate or self-rule people

We do not have a king in Šura. Is the Emperor the Trustee, or the entire Senate, or the sovereign people?

Jarap jat Sačutu suč, ijora pašap suč atej.

rule in Sačutu be.prog.3s / government pointing be.prog.3s emperor

The ruling in Sačutu is that the government itself stands for the emperor.

Jat saččeg si jeŋu audeg?

in authority of divinity how

What of the ultimate religious authority?

Jat Sačutu pit siš pač išapa / ŋok in dej an anebe šarap suš, zun mor suč jarap.

in Sačutu believing be.prog-1p strong agreement / two of three all teacher-pl agreeing be.prog-3p / therefore that.one be-prog.3s rule

In Sačutu we believe in strong consensus. If two thirds of the teachers agree, then that is the ruling.

Jat Fanpita modeg teŋŋir aminkiran suč Jippir. Jat čelepau, mo teŋŋir aminkiran.Our “theory vs. practice” becomes CT “books vs. hands”.

in Fanpita only saint speaking.for be.prog-3s Jippir / in book-pl / one saint speaking.for

In Fanpita, only a saint can speak for Jippir. In theory any saint can do so.

Jat toro, jarap suč, mo teŋŋir nisuč isača, soga an gok gomrarulu.

in hand-pl / rule be.prog.3s / one saint can-be.prog.3s truth / except all other deny.prog.3p>3s

In practice the ruling is “Though one saint is truth, this is not so if he is opposed by all others.”