| Rants for | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| |

|

It's really Dave McKean's film-- McKean drew/constructed all the covers for The Sandman and did the art for Gaiman's Violent Cases, and the movie is above all a trip into McKean's brain. Leave a popcorn trail so you can get out again.

The story centers on a 15-year-old girl, Helena, whose family runs a circus, a sort of Cirque du Soleil without the uproarious success. In a nice Gaimanian twist, she hates it there and wishes she could live a normal life. Needless to say, this particular dilemma won't be solved without entering a fantasy world-- essentially, her own drawings come to life.

It's marvelous to see, and Stephanie Leonidas is cute and game as Helena, and you should see it, because there should be more eccentric $4 million movies like this. That said, yes, I'm going to complain, or whinge, as our authors might say. I suggest skipping the next two paragraphs till after you've seen the film.

Gaiman has said that the process of writing the film was surprisingly difficult-- he and McKean had different ideas for where the film should go. Unfortunately, I think this disagreement ends up on the screen. For instance, Gaiman says that the "anti-Helena" idea is his: there's a dark double of Helena in the dreamworld who escapes, replaces Helena in the real world, and acts out a load of adolescent angst. Now, I think that'd be a great movie right there-- only we really don't get to see it, except in glimpses. And it doesn't really cohere with the rest of the story, and it seems to have no consequences.

Gaiman also reports that McKean is strangely literal-minded about fantasy-- for him, it has to have some clear metaphorical connection to reality. And I'm afraid it does. Helena's dreamworld features dream versions of her parents and an edifying moral struggle, which don't go well with the bits of visual whimsy and the artificial puzzles that keep cropping up. Gaiman's worldview is usually liberating; this one is oddly constricting. It's probably not quite intentional, but the message of the movie seems to be that teenage girls shouldn't talk back to their mothers or kiss boys, because that's giving in to the Dark Side.

If you haven't seen it, start at the beginning with Firefly, the TV series. The upside to its sad cancellation is that it's easy to catch up; and Serenity is best enjoyed as the last episode of the series.

Plus, though it's a great movie, it's even better as a TV series. The film seems to feel that it has to blow you away; while the TV episodes, though some are quite tense, are a little more leisurely, giving time for character interaction and long-term plot development.

Don't get turned off by the "Westerns in space" angle. I don't like Westerns as a rule, but I liked these. It's actually not a bad sf idea: the frontier of a rapidly expanding spacegoing society is likely to be mostly low-tech: it's going to take time for a colony to afford the futuristic turrets and domes. And though the captain is built up as a macho strong guy, he's also regularly deflated-- the actor, Nathan Fillion, can move in an instant from drama to comedy. (And arguably the toughest and smartest person on board is his second-in-command, a woman.)

| |

|

The new plan for Iraq is full of fine goals, and yet remains fatally vague about how they'll be achieved. On the plus side, the NSC document recognizes and addresses many of the serious problems we face. On the negative side, it has nothing at all to say about some of the key issues. And you can't solve problems that you can't even see.

The maddening thing is that Bush's incompetence will impede almost any attempt to clean up the mess. If we leave too soon, the likelihood is that Iraq will collapse into a nasty and protracted civil war. Maybe the opposite strategy will work-- beef up our forces till they can really secure the country-- but after two more years of Rumsfeld the army won't be in any position to ramp up; and diplomatic bridges have been so thoroughly burned that no one else is going to feel like helping out.

| |

|

My first impressions are good. It's very pretty; the 3-D rendering is impressive; the religions are fun (I enjoyed making Otto von Bismarck convert to Hinduism); many of the tedious bits are indeed gone. The Great Leaders seem integrated into the game now. Civ is all about control, so the randomness of Civ3's Leaders wasn't much fun.

I'm still learning the units and the tech tree; but so far it seems a little easier than Civ3. The other civs seem a little less aggressive, and less reliant on the Stack o' Doom; the battle system is more transparent and thus more satisfying. I had a devil of a time just now taking Novgorod from the Russians in modern times-- each unit has different attack and defense strengths, and they all favored Peter-- but being able to mouse over and see the combat odds is very educational.

Our whole development team has gone out and bought it-- even Fred, who's more of an FPS guy-- and we've tried the multiplayer version once. It's really smooth, not much slower than a single player game. I had a lot of fun playing a duel with my boss. We coexisted peacefully till we ran out of room. Thanks to the spy effect of religions, I could see that his mind wasn't on defense-- he was defending a few cities with just one Archer-- so I built about eight War Elephants and invaded.

I took out all but three of his cities; if I were playing the AI it would let me talk peace, but Jeffrey wouldn't hear of it. So I had to finish him off-- fortunately I could get Cossacks and he hadn't yet got Riflemen.

It's interesting that the graphics, though much more elaborate, are more cartoony. Civ3's graphics, by comparison, seem prettier, but more static.

More later, I think I have time to start another game...

Update: I did. Thought of one cavil though: the histogram is seriously lame. Whose stupid-ass idea was it to not label the countries?

| |

|

I'm sure I'm not the only new Wikipedian who's gone through a period of wishing the entire web was like this-- where if you see an error you just correct it. I tried to correct an error at imdb once... good Lord, what a horror. It took about a dozen screens merely to get into a position where they might consider your fix.

I can't really agree with my friend Lore, who thinks that Wikipedia loses credibility because egotists can edit entries about themselves. I think the intersection of people who are interesting enough to look up and those who have the time to mess with Wikipedia is pretty small.

What about accuracy? On the plus side, it has to be a pretty obscure subject for me to second-guess Wikipedia. On the other hand, outside of 'things everyone knows', with geekish values of 'everyone', it trails off into stubs and eccentricity. I've been surprised to encounter people who believe that it's written by experts, like a "real encyclopedia". By no means. At its best it's written by knowledgeable amateurs.

Wikipedians worry a lot about "neutral point of view", which must make epistemologists and lit majors and Akira Kurosawa turn apoplectic or in their graves, as appropriate, but which is probably essential for any web project that allows free input. Otherwise everything would be hijacked by cranks. The cranks still come, but they can't cause anywhere near the trouble they can in (say) a newsgroup.

The biggest frustration is that careful work may be undone at any time by contributors with more enthusiasm than knowledge. I watch the Inca Empire article, for instance, which attracts an amazing amount of vandalism. That gets erased quickly, but harder to deal with are people who heard something somewhere-- that the Incas had writing, that Tawantinsuyu means this or that-- and cheerfully revise more accurate accounts. Just tonight some doofus added their own unnecessary summary, featuring writing like this: "With more than six million people it contained parts of Peru, Ecuador, Bolicia, Chile, and Argentina. Full of highlands, the Inca polty dates back to ca AD 1200. In AD 1428 there was territorial expansion."

On the other hand, it's cheering to look at the history of almost any article, and see that it's gone in a period of two years or so from a couple of sloppy paragraphs on the order of the above quote to a pretty decent overview. It should be interesting to see how it develops in a few more years.

Update: Heh, the cheesy additions I mentioned above got removed very quickly. It does point up a tricky bit with the Wikipedia model, however: it's very high-maint. I'd hate to see high entry barriers put up, but I can't see the current arrangement lasting for 10 or 20 years.

| |

|

You've had liberalism on the retreat for a quarter-century; you've been in power for ten years now, and in charge of all three branches of government for five.

And you're about to lose it all.

You may bristle at that; but don't bother. Your coalition is balanced on a knife-edge: your man won in 2004 with less than 51% of the vote. It'd take just a puff to blow the electorate the other way; and Katrina was more than a puff.

To be honest, it's fine with me if you learn no lessons and continue on as before, because you'll be defeated sooner rather than later. But there's another way, and I don't mind pointing it out. I'd rather have a responsible than an irresponsible conservative opposition.

Put simply, it's time to grow up.

Revolutions are fun, aren't they? You get to track mud into the Winter Palace and spend the government's money your way and make your enemies apoplectic without getting hit back. But you don't get to do that forever. Either you grow into the job and realize that you are the establishment now-- or you'll be thrown out. Even Kim Jong-il is going to get his comeuppance one day.

Growing up doesn't mean abandoning conservativism. In fact, it means returning to some of your core values: responsibility, pragmatism, and decency.

Bush's speech Thursday night was a good start. Katrina was a big honking demonstration that government is needed for some things and that the US is not ready for a major terrorist attack, and Bush recognized this.

But it's only a start. Growing up means some specific changes.

The reality, say several aides who did not wish to be quoted because it might displease the president, did not really sink in until Thursday night. Some White House staffers were watching the evening news and thought the president needed to see the horrific reports coming out of New Orleans. Counselor Bartlett made up a DVD of the newscasts so Bush could see them in their entirety as he flew down to the Gulf Coast the next morning on Air Force One.Aides need to sit the president down to make him see what the rest of the country can see on CNN? Seriously, folks, do any of your projects matter to you at all? Iraq, for instance? With this kind of non-leadership, they're all going to fall apart.

The reason I'm mad as hell over Katrina is precisely because I'm a conservative and this kind of thing is exactly what government is for. Bush in this sense is not now and never has been a conservative. A man who explodes government spending but can't run a war or organize basic civil defense is simply a fiscally reckless incompetent.This isn't about limited government. It's about incompetent government. Running down "government" in general produced the latter, not the former. Now that you're in charge of the government, you're expected to make it work.

| |

|

The best thing I've read about the disaster all day, however, was my friend Greg Peters's account of the planning sessions. (Bottom line-- but don't settle for the bottom line, read the whole thing-- FEMA "promised the moon and the stars", and didn't deliver.) I've been checking Greg's blog daily in hopes that he'd give some insight, and this will hopefully be just the first installment.

| |

|

Four years after 9/11— four years, the time it took for us to enter and win World War II— we've gotten a surprise test of what would happen in the case of a massive terrorist attack. And now we know: Bush and Cheney would go on vacation; the Speaker of the House would order the area bulldozed; tens of thousands of Americans would be left to misery and death.

And that's how they treat red states.

New Orleans and Biloxi are not rich cities. They are poor southern cities disproportionately filled with poor southern people — people who may not have reliable transportation, people who live hand-to-mouth, people who have nowhere else to go, even if they had the means to get there.And more passionately by musicologist Ned Sublette:And the evacuation was little more than a vague order to get the hell out — under your own power and at your own expense. If you have, at your immediate disposal, reliable transportation, money for gas, and either distant family OR money for shelter, then this isn't a big deal. Of course you leave. You pack up everything you can and you head for higher ground. But it is somewhat less easy to do if you are lacking any one of these things, AND you have been informed that what little earthly lot you may claim is about to be destroyed. Do you hang on and try to save what you can? Do you let it go and return to less than nothing?

What the hell do you do?

The poorest 20% (you can argue with the number — 10%? 18%? no one knows) of the city was left behind to drown. This was the plan. Forget the sanctimonious bullshit about the bullheaded people who wouldn't leave. The evacuation plan was strictly laissez-faire. It depended on privately owned vehicles, and on having ready cash to fund an evacuation. The planners knew full well that the poor, who in New Orleans are overwhelmingly black, wouldn't be able to get out. The resources — meaning, the political will — weren't there to get them out.Perhaps Sublette is exaggerating? No such luck:

Brian Wolshon, an engineering professor at Louisiana State University who served as a consultant on the state's evacuation plan, said little attention was paid to moving out New Orleans's "low-mobility" population - the elderly, the infirm and the poor without cars or other means of fleeing the city, about 100,000 people.��And most sadly by people posting to the New Orleans Times-Picayune missing persons forum:At disaster planning meetings, he said, "the answer was often silence."

I'm looking for Julia — and Izma —. I was told that they were airlifted by the National Guard from LaFon to the New Orleans airport. Julia is 82 years old, confined to the bed and can't speak.What were these people supposed to do? Oh, right, obey the mandatory evacuation order. Which was issued on Sunday, when Greyhound had already shut down, when Amtrak had already shut down, when the last airlines were shutting down.THERE ARE ABOUT 40 ELDERLY & MENTALLY DISABLED CITIZENS TRAPPED IN AN APT COMPLEX AT 1226 S. CARROLLTON AVE. ..NO FOOD OR WATER & THEIR CAREGIVES LEFT THEM PRIOR TO STORM...THEY MAY NOT HAVE ENOUGH INSIGHT TO MAKE THEMSELVES NOTICEABLE TO RESCUERS...

Please go to 2110 Royal St. apt 719 and rescue my 81 year old mother, Rosalie — who is trapped in the building with many other elderly people in need of medication, food, and water. I beg for your help before they dehydrate.

Lisa — is looking for Flora —. Flora is on medication for high b/p and blood sugar and may need medical attention. The last time I spoke to her she was stranded in her house on the 2nd floor. Age: 70

Bush's first priority, of course, was covering his ass. "I don't think anybody anticipated the breach of the levees." He was wrong.

Was the disaster hidden in bureaucratic reports? No, it's been trumpeted in the media for years, including the possibility of levee failure. The Times-Picayune had a five-part series on it. A Scientific American article the same year noted, "New Orleans is a disaster waiting to happen." A FEMA study from 2001 put a hurricane in New Orleans among the top three catastrophes that might hit the US.

FEMA director Michael Brown didn't know till a CNN reporter told him that there were tens of thousands of people at the Convention Center, though local officials had been directing people there for days.

Condoleeza Rice spent Thursday seeing a Broadway show, playing tennis, and spending several thousand dollars on shoes. When a fellow shopper berated her for her callousness, Rice had her evicted from the store.

What could a Secretary of State do during such a crisis? Well, how about handling snafus like this: Canada has emergency supplies ready to ship, including emergency water purifiers— but can't get permission to enter the country.

Or maybe she could expedite the aid offered by Belgium, Canada, Russia, Japan, France, Germany, Britain, China, Australia, Jamaica, Honduras, Greece, Venezuela, the Organization of American States (i.e. everyone in Latin America), NATO (i.e., everyone in Europe), the Netherlands, Switzerland, Greece, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico, South Korea, Israel, Sri Lanka, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Brown: I've just learned today that we ... are in the process of completing the evacuations of the hospitals, that those are going very well.It's not just New Orleans. From the Biloxi, Mississippi Sun Herald:

CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta: It's gruesome. I guess that is the best word for it. If you think about a hospital, for example, the morgue is in the basement, and the basement is completely flooded. So you can just imagine the scene down there. But when patients die in the hospital, there is no place to put them, so they're in the stairwells. It is one of the most unbelievable situations I've seen as a doctor, certainly as a journalist as well. There is no electricity. There is no water. There's over 200 patients still here remaining. ...We found our way in through a chopper and had to land at a landing strip and then take a boat. And it is exactly ... where the boat was traveling where the snipers opened fire yesterday, halting all the evacuations.Brown: I've had no reports of unrest, if the connotation of the word unrest means that people are beginning to riot, or you know, they're banging on walls and screaming and hollering or burning tires or whatever. I've had no reports of that.

CNN's Chris Lawrence: From here and from talking to the police officers, they're losing control of the city. We're now standing on the roof of one of the police stations. The police officers came by and told us in very, very strong terms it wasn't safe to be out on the street.Brown: I actually think the security is pretty darn good. There's some really bad people out there that are causing some problems, and it seems to me that every time a bad person wants to scream of cause a problem, there's somebody there with a camera to stick it in their face.

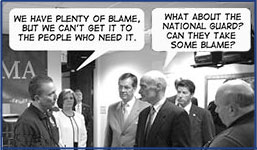

Chertoff: In addition to local law enforcement, we have 2,800 National Guard in New Orleans as we speak today. One thousand four hundred additional National Guard military police trained soldiers will be arriving every day: 1,400 today, 1,400 tomorrow and 1,400 the next day.

Nagin: I continue to hear that troops are on the way, but we are still protecting the city with only 1,500 New Orleans police officers, an additional 300 law enforcement personnel, 250 National Guard troops, and other military personnel who are primarily focused on evacuation.

Lawrence: The police are very, very tense right now. They're literally riding around, full assault weapons, full tactical gear, in pickup trucks. Five, six, seven, eight officers. It is a very tense situation here.

On Wednesday, reporters listening to horrific stories of death and survival at the Biloxi Junior High School shelter looked north across Irish Hill Road and saw Air Force personnel playing basketball and performing calisthenics. Playing basketball and performing calisthenics!New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin blows up:

I don't want to see anybody do anymore goddamn press conferences. Put a moratorium on press conferences. Don't do another press conference until the resources are in this city. And then come down to this city and stand with us when there are military trucks and troops that we can't even count.Don't tell me 40,000 people are coming here. They're not here. It's too doggone late. Now get off your asses and do something, and let's fix the biggest goddamn crisis in the history of this country

As blogger righthandthief notes, "I've no doubt that Hastert voiced similar sentiments in 1993 when many towns in Southern and Western Illinois flooded."

Daniel Gross takes the time in Slate to explain why Katrina will cause more economic devastation than 9/11, and why the Gulf Coast is important— in case you couldn't tell from the price hikes at your local gas station.

Katrina, for example, has already created havoc in the energy sector. Nine of the region's 14 refineries are shut, representing 12.5 percent of U.S. refining capacity, according to the Financial Times. This week, the United States also lost about 20 percent of its oil production and a big chunk of natural-gas production. As a result, the pipeline systems that originate in the Gulf Coast region and snake throughout the Southeast and Atlantic seaboard aren't functioning properly. The instantaneous result: higher costs for gas and heating oil in states far beyond Louisiana.So it's not merely a matter of a bunch of defiant poor blacks who can be bulldozed away. It turns out we need our largest port....As the Wall Street Journal notes, New Orleans ports "handle roughly half of the corn, wheat and soybeans exported from the U.S., much of which reaches the city on barges traveling on the Mississippi River." Katrina has already screwed up the vital supply chains that funnel goods from the Midwest to global markets and from global markets to the Midwest.

By the way, everybody who's snarking over the foolishness of building a city below sea level... are you willing to apply the same logic to building a city in a desert, like Phoenix or Los Angeles? Or how about building our most populous state in an earthquake zone?

The possible devastation of a hurricane strike on New Orleans has been known for years. 9/11 was a kick in the pants to start preparing rapid, large-scale disaster responses. And Bush has been delaying planning, reducing funding, and diverting resources to Iraq, as an Editor & Publisher story makes clear:

Yet after 2003, the flow of federal dollars toward SELA dropped to a trickle. The Corps never tried to hide the fact that the spending pressures of the war in Iraq, as well as homeland security — coming at the same time as federal tax cuts — was the reason for the strain. At least nine articles in the Times-Picayune from 2004 and 2005 specifically cite the cost of Iraq as a reason for the lack of hurricane- and flood-control dollars.It's not just money; Bush's Iraq adventure swept away a third of the Louisiana and Mississippi National Guard and much of its best equipment:On June 8, 2004, Walter Maestri, emergency management chief for Jefferson Parish, Louisiana; told the Times-Picayune: "It appears that the money has been moved in the president's budget to handle homeland security and the war in Iraq, and I suppose that's the price we pay. Nobody locally is happy that the levees can't be finished, and we are doing everything we can to make the case that this is a security issue for us."

One of the hardest-hit areas of the New Orleans district's budget is the Southeast Louisiana Urban Flood Control Project, which was created after the May 1995 flood to improve drainage in Jefferson, Orleans and St. Tammany parishes. SELA's budget is being drained from $36.5 million awarded in 2005 to $10.4 million suggested for 2006 by the House of Representatives and the president.

JACKSON BARRACKS — When members of the Louisiana National Guard left for Iraq in October, they took a lot equipment with them. Dozens of high water vehicles, humvees, refuelers and generators are now abroad, and in the event of a major natural disaster that, could be a problem. "The National Guard needs that equipment back home to support the homeland security mission," said Lt. Colonel Pete Schneider with the LA National Guard.Or here's Tim Naftali from Slate:

What has DHS been doing if not readying itself and its subcomponents for a likely disaster? The collapse of a New Orleans levee has long led a list of worst-case urban crisis scenarios. The dots had already been connected. Over the last century, New Orleans has sunk 3 feet deeper below sea level. With each inch, pressure grows along the levees. Meanwhile the loss of wetlands and the shrinking of the Gulf Coast's barrier islands have reduced the natural protection from hurricane winds. The weakness of the levees was underscored in a 2002 wide-ranging exploration of New Orleans' hurricane vulnerability by the New Orleans Times-Picayune, one of many grimly vindicated Cassandras. The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, which built the levees and continues to manage them, told the paper then that there was little threat of a levee's collapse. But the corps admitted that its estimates were 40 years old and that no one had bothered to update them.The Washington Post has a very sobering article on the immense amount of rebuilding that will be necessary in New Orleans. The work— and the present plight of flooded residents— is exacerbated by lax regulation allowing the flood waters to be contaminated:

Louisiana, a center of the oil, gas and chemical industries, "was known for its very weak enforcement regulations," Kaufman said, and there are a number of landfills and storage areas containing "thousands of tons" of hazardous material to be leaked and spread.Paul Krugman in the New York Times:

Last year James Lee Witt, who won bipartisan praise for his leadership of the agency during the Clinton years, said at a Congressional hearing: "I am extremely concerned that the ability of our nation to prepare for and respond to disasters has been sharply eroded. I hear from emergency managers, local and state leaders, and first responders nearly every day that the FEMA they knew and worked well with has now disappeared."But who needs someone competent in charge of disaster recovery? Michael Brown comes to FEMA from a staff position at the International Arabian Horses Association.

Bush was off stumping to support his Iraq war this week, as New Orleans drowned. You'd think he might have learned from Baghdad about the importance of establishing order fast. But no. As a guy named Hunter blogged on dailykos:

The common televised theme is of reporters traveling to hard hit areas in New Orleans or the smaller communities, and reporting no FEMA presence, no National Guard presence, no food, no water, no help — and this is day 5.On the bright side, at least the New Orleans looters had ready access to guns. Thank the NRA that Americans could express their God-given right to shoot at the people trying to rescue them!The lawlessness is rampant. It's important to note, however, that the lawlessness wasn't rampant on Monday. It wasn't rampant on Tuesday. We heard only twinges of it on Wednesday. Today, from the sounds of the reports, a city devoid of all hope devolved into absolute chaos.

More dangerous, because it's more common and seems almost reasonable, is the suggestion that we shouldn't "politicize" the disaster. It's all right to blame the victims, but it's unacceptable to point a finger at Our Leader.

Wrong lesson. Disasters have to be turned into politics. Disasters are the proving ground of morality: in them, you find out what moralities really mean, who the heroes really are, what the serious problems really are. And we've found out this week what "compassionate conservativism" amounts to, what the Bush administration cares about (repealing the estate tax, it turns out), and what happens, as Tom Tomorrow puts it, "when you elect leaders ideologically committed to the notion that government isn't good for anything."

Disasters make people ask questions. And the questions keep getting asked even after the disaster itself is taken care of.

In my web reading today, I found this best expressed by a conservative, David Brooks of the New York Times:

Then in 1927, the great Mississippi flood rumbled down upon New Orleans. As Barry writes in his account, "Rising Tide," the disaster ripped the veil off the genteel, feudal relations between whites and blacks, and revealed the festering iniquities. Blacks were rounded up into work camps and held by armed guards. They were prevented from leaving as the waters rose. A steamer, the Capitol, played "Bye Bye Blackbird" as it sailed away. The racist violence that followed the floods helped persuade many blacks to move north.Brooks's story is a welcome reminder that things do progress, though with excruciating slowness. Things aren't as downright vicious as they were eighty years ago. And that's because people politicized the disasters, because they didn't give their leaders a free pass, because they demanded better.Civic leaders intentionally flooded poor and middle-class areas to ease the water's pressure on the city, and then reneged on promises to compensate those whose homes were destroyed. That helped fuel the populist anger that led to Huey Long's success. Across the country people demanded that the federal government get involved in disaster relief, helping to set the stage for the New Deal. The local civic elite turned insular and reactionary, and New Orleans never really recovered its preflood vibrancy.

There's a lot of people who need to face some very insistent questions. (Not just at the federal level— Lousiana has a long history of misgovernment, and the city bears responsibility for the botched evacuation.) And I'll wager that not even Karl Rove will succeed in keeping people from asking anymore.

| |

|

So what benefits does Weisberg see in maintaining the opposite? None, really; that's the bizarre part. Indeed, he can see the political benefits of downplaying the conflict. The sticking point seems to be that he feels that it is "almost too obvious to require argument" that evolution erodes faith.

"Too obvious" is usually a bad sign: it means that the writer isn't going to bother to argue, and in fact Weisberg doesn't. He simply asserts that evolution "provides a better answer to the question of how we got here than religion does." This begs the question— he's assuming the incompatiblity in order to demonstrate it.

Ironically, Weisberg agrees with the creationists on another point— that evolution is an "unguided, random process"— and is just as wrong.

Evolution is emphatically not random. It's driven by positive feedback; and that makes all the difference. That's why it creates interesting organisms, not just useless blobs of inert DNA.

This fascinating toy, which I was going to write an unrelated rant about, makes a good analogy. It's a Flash program which takes a rough sketch and scribbles over it— generally rather improving the original. The example at right is what it did with a simple sketch of mine.

The program has random elements— if you watch it run, you can see it draw lots of tiny little lines in apparently random ways. But is the resulting picture random? Certainly not; the program has a feedback mechanism, in that it's guided by the user's initial sketch.

By the way, I hope no one takes any of this as support for "intelligent design", which is an underhanded attempt to get religious doctrine into science classes. You can believe in it if you like; just don't pass it off as science. The kicker: no one who believes in "intelligent design" is willing to actually treat it as a scientific theory— that is, to subject it to rigorous attack where there is a realistic chance of falsification.

| |

|

Other neat things:

A few complaints:

| |

|

What you want to know next, of course, is my opinion on what order to watch the whole epic in. I went back and forth on this a bit, but I'm pretty sure now that you need to watch them in the order they came out. Episodes IV and V would just be spoiled by knowing too much about Vader and Yoda. (Especially the wonderful scene where Luke first meets Yoda.) And the power of the last half-hour of III is mostly based on knowing what comes next.

And now, Batman Begins. There's no competition— this is the best Batman movie yet. Burton's Gotham City was more stylishly dark; but it was a set designer's movie, with a horrible script. Christopher Nolan shows what you can do with an actual story, some actual themes, and some actual actors. (Jack Nicholson was a standout in Batman; but I'm sorry, all Michael Keaton had going for him was a single sustained pout.)

It was fun to see bits of Chicago poking through the CGI. Strange, though, to see Dr. Kinsey lecturing Bruce Wayne on the need to destroy decadent cities.

I think it would have been a better movie if its ambitions were a little more modest. It does an impressive job of making costumed vigilante seem like a reasonable career move; there's a lot of thought (for a superhero movie) about themes of corruption, fear, and honorable resistance. And then it's all thrown out in order to strut out one more James Bond megalomaniac. This is silly, Chris: Batman isn't about stopping genocide; he's about frightening street thugs.

The '20s and '30s must have been highly traumatic: they spawned not one but two genres devoted to redemptive violence: the hard-boiled detective story and the superhero comic. Both genres charged off in all directions from this starting point, and curiously, Frank Miller has taken both back to their roots, with Sin City and The Dark Knight Returns, the brilliant and nasty work that underlies both Burton's and Nolan's Batman.

As happens so often in art, Miller and Nolan succeed in giving us something new by giving us something retro. Sin City barely nods at anything past 1950; and Nolan's Gotham City, a huge city entirely in the pocket of a single crimelord, is essentially the world of The Untouchables. And for the most part we don't live in that world any more. (An Internet page suggests that organized crime accounts for 1-2% of US GNP. That's enormous in absolute terms, but it doesn't exactly dominate our lives.)

The insistent realism of Batman Begins raises the question: why has no one ever done this? You can't always find a radioactive spider when you need one; but why has no one tried to become Batman, famously a character with no superpowers? Why doesn't this work in the real world?

There's a bunch of answers to this, such as, criminals are not such a cowardly and superstitious lot that they're afraid of men in leotards. More than that, we know of course that it's fantasy, that lawlessness isn't solved by car chases, that vigilantes are not good at forensics, that a city that relies on strong-arm law enforcement generally has a lot more force than law. We do know that, now don't we?

| |

|

Ferguson's main thesis is provocative: empires aren't necessarily bad; indeed, they can be measurably better than leaving people to their own devices. His best case for this is the tremendous failure of post-colonial Africa. More subtly, he shows that colonialism produced far more investment in developing countries: in the Victorian era, 49% of British overseas investment went to Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In 2000, about 12% of First World overseas investment went to developing nations. Colonial or semi-colonial governments also had the backing of central banks and could thus borrow at steep discounts.

Not only are Americans in denial about their empire, but their denial generally guarantees failure. Our frequent interventions in Latin America, he points out, have benefitted neither ourselves nor the locals— we might well have done better to rule Cuba or Nicaragua directly, as we do Puerto Rico. (E.g., its per capita income is four times higher than theirs.)

Americans want to be in and out quickly, as opposed to the British, who had a reliable stock of nationals willing to pack up and move to the tropics for a lifetime. Three quarters of the members of the Indian Civil Service in the 1930s had attended Oxford or Cambridge. How many graduates of Yale and Harvard are eager to go rule Iraq or North Korea?

"But we did well in Germany and Japan." We did, and Ferguson points out that one reason is that we were willing to keep troops there for half a century. More interestingly, he points out that we hardly knew what we were doing in either country. The original plan, in fact, was to punish both countries and prevent re-industrialization; this was abandoned only when it was realized that people would starve, and the occupation would be an ongoing financial drain, if the countries didn't develop. The Marshall Plan helped, of course, but only 10% of it— about $1.2 billion— went to Germany; a similar amount went to Japan. Since our record with other client states is so poor, we really can't say that we know what we did right in Germany and Japan and that we could repeat that success elsewhere. Much of the success is probably due to the Germans and the Japanese anyway.

Ferguson is an honest enough writer that he himself points out the best counter-arguments to his position. The weak point in the case for liberal empire is India, whose production hardly grew at all in the last century of British rule. If he were writing in 1985, India's lackluster attempt at socialism would help his case. But it's hard to maintain that today's hard-working, entrepreneurial India would have happened under colonialism.

He chides Americans for not knowing the educational story of Britain's conquest of Iraq in 1917, complete with a quick march to Baghdad, a years-long resistance, and frequent promises to leave. On the other hand, he doesn't make as much of the fact that the British ultimately failed: the institutions they established were jettisoned by the Iraqis, and the long period of semi-colonialism led to the rise of a virulently anti-Western regime. (Likewise, the pathetic military coups that destroyed African parliamentarism were begun by the US in the Congo. Africa didn't just slide into its decades of misery; it was pushed, in the name of opposing communism.)

The soft underbelly of Ferguson's liberal imperialism is that tricky thing called the consent of the governed. I'm not talking about principle here: Ferguson is probably quite right that certain countries would be better served by colonial rule, and I think the Left goes far wrong when it defends state sovereignty and anti-Americanism above development, democracy, and justice. But the rogue states that could benefit from colonialism are precisely those that would most strenuously resist it.

| |

|

A long and intelligent and entirely wrong-headed review over at Planet Magrathea makes the point that Douglas Adams was at base a great sketch comic. That's true to a large extent, and it's part of the appeal of the radio show and the book. A lot of Adams's humor comes down to people bickering senselessly, on and on, in inappropriate situations. Your planet is blown up and you whine about not being able to brush the dog. You've got the most intelligent computer ever in front of you and you complain about the labor implications. You're a cop shooting at some perps and you find yourself reassuring them that you're a sensitive guy who they'd probably like if they met you socially.

It's great stuff, it's fun, and it's not a movie. Even Monty Python couldn't make this stuff work for an hour and a half at a time, except in Holy Grail, and that only worked because they worked hard to give it an un-sketch-like thematic unity.

Besides, to hope for a great sketch movie is to sell Adams short. The video game is very Douglas Adams too, and it's nothing like a BBC sketch. Dirk Gently isn't a series of sketches. The Guide excerpts aren't sketches (and therefore they work pretty well in the movie, as interludes). Above all, there's the Adams worldview: the universe is incomprehensible and insane, so you'd might as well enjoy it. Since I first read the books, I've felt that once we actually get out into the galaxy, Douglas Adams is more likely to be a good guide than anyone else in science fiction. Most other writers' visions are too monochromatic.

The arguments over whether the movie is true to Adams probably won't stop till we can read his last draft and compare it to the shooting script. However, I won't at all be surprised if we find that most of the things the die-hards hate are pure Adams— for good or for ill. Very likely he understood that it wouldn't work as a series of sketches, and concentrated on more movie-like ideas. And the movie is at its best when its ideas are quick and visual: painting Ayers Rock; the characters done in knitting; the anti-idea spatulas; the Point of View gun.

As for "It's incomprehensible", I have to ask, who are we fooling? If you've never read the books, well, yes, you may not like it very much. (My wife hasn't, and didn't.) But packing the movie with all our favorite Adams sketches would make it less rather than more accessible.

As an example, there's plenty in the movie about towels, but no explanation of why you should always know where your towel is. But you know, we've read the book. We know that passage; why do we need Stephen Fry to read it to us? Why not take it as read, and enjoy the fact that Ford Prefect, throughout the movie, is demonstrating the idea by using his towel in half a dozen different ways?

As for plot holes... yeah, yeah. After seeing the movie, I sat down and and re-read most of the books. The deep and dirty secret is... Douglas Adams kinda sucks at plots. We hardly notice because the foreground is so lively, but the plot doesn't really stand up to analysis. Characters are shuffled about just where they're needed; miraculous aids appear and are forgotten; dangers appear and are dismissed with a joke. (Re-read the end of HHGG and tell me that two pandimensional beings who can pay for the construction of a planet can be put out of the picture by some humanoids flinging around design awards.)

(While I'm at it, I can't help mentioning another annoying fact: Adams is pretty uneven. Some of the jokes fall flat, some of the bits go on too long, some of the dialogues seem padded; he relies way too much on prefixing things with "ultra" and "mega". This is one reason the Planet Magrathea guy shouldn't get on his high horse about Marvin in the movie being asked for a hand. We're talking about an author who's capable of writing that an editor is "missing, presumed fed.")

Some valid criticisms of the movie:

Now, as Jane Walmsley explains, this is pretty standard for British humor— where American comedians are archetypically the smart, cheeky outsider in a stupid world (Groucho, Bugs Bunny, Bill Murray, Eddie Murphy, Garfield, Uncle Duke), the British comic is a complete idiot in an ordinary world (Bertie Wooster, Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore, Lister and Rimmer, Mr. Bean, Arthur and Zaphod).

But, it's hard to make this work in a movie. Somehow, it's fun to read about kneebiters and assholes, and even to watch them on TV, but not so much so to watch them for ninety minutes in a movie theater.

Episode III, now. What are the chances that won't suck?

| |

|

People love to work out definitions, as if this told them something about the world. In Understanding Comics, to use a neutral example, Scott McCloud defines comics as juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence blah blah blah. It's nice to say what you're going to talk about, but it would have been simpler and no less accurate just to enumerate: "I'm going to talk about comics, but I won't be talking about single images or animated cartoons."

He borrows this method from academics, who love to begin by defining their subject. Generally you'd might as well skip to Chapter Two, where they'll forget about their own definition and start to actually talk about things.

When it comes to political terms, definitions are little more than propaganda. Libertarians like to talk about "freedom"— with a very idiosyncratic definition of "freedom" such that if you can't leave your house because the roads are privatized and you can't get a job because the employers don't care to offer a living wage, you are enjoying absolute "freedom." If you accept this, they can then paint their opponents as enemies of "freedom".

Anyone can play this game; for instance, I can define liberals as people who are for prosperity, liberty, and justice. Naturally, then, anyone who's not a liberal is for poverty, slavery, and oppression.

From a linguistic point of view, definitions are pointless for a bunch of reasons.

One reason linguistic analyses are so complex is that meanings come in clusters. This is why amateur definitions are so gerrymandered: people are attempting to find the common elements of multiple senses. But a word's referents may well share no attributes in common. (Try to think of a definition of game that covers sports, board games, puzzles, poker, solitaire, SimCity, war training, rhetoric, and the Prisoner's Dilemma. They're all related, but they're not all amusing, not all competitive, not all multi-player, not all inconsequential, etc.)

Next, linguists hoped to find semantic primitives which could be used to define everything else. Again, it didn't work. You can define 'bachelor' as 'unmarried adult male', for instance— but 'marriage' and 'adult' (and even 'male', in social terms) aren't primitives at all; they're complicated cultural constructs.

This applies even more strongly to politics. Political movements don't arise by standing for abstract principles in a vacuum. You learn something if you know what they're for, but you don't get the whole picture till you know what they're against. Very often political movements don't even make sense till you know how they arose, who they fought against, and what some of the arbitrary issues were. There's nothing in the platform of the Republican Party, for instance, that would allow us to predict that Republicans in 2000 would stand against legally mandated recounts and against counting dangling chads.

| |

|

In an attempt to demythologize, I've just been reading about FDR— specifically, William Leuchtenburg's Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. I expected there would be a good deal of contemporary opposition to FDR that's been forgotten; but really, I didn't imagine the depth of it.

It wasn't just the conservatives— who anyway were at their lowest ebb; in 1936, for instance, the Republicans were reduced to 21 Senate seats. The biggest threat was arguably on the left, from populists like Huey Long, pie-in-the-sky welfare statists like Francis Townsend, and outright socialists who felt that Roosevelt wasn't going far enough, that the country needed industrial planning at the least, and probably nationalization of industry.

The conflict also played out within Roosevelt himself. By nature he was an experimenter and a tightrope walker. For the most part this served him well: he negotiated his unprecedented predicament adroitly, with an instinctive sense of when to push and when to bow to facts. And in allowing infighting among his lieutenants he was only crazy like a fox: it allowed him to try several things at once.

But sometimes his conflicting impulses bridled a program that should have been much more successful. For instance, he worsened the recession of 1937 by scaling back New Deal programs. He always hoped to work with the rich and with big business, and probably gave them too much leeway for too long. On the other hand, his anger over the Supreme Court's rejection of a few New Deal agencies was foolishly overblown: his initial bluster did the trick— the Court started upholding his programs— but he prolonged the fight for four months more, permanently damaging his support in Congress.

Like Lincoln, Roosevelt was largely responsible for reframing the political framework of the country— and never entirely transcended the old order. He retained a fundamental wariness of deficit spending and government relief. Like many thinkers of the day, he idealized small business and farms— an America already of the mythic past in his own time. He made government responsive to far more than the WASP Northeastern elite which had traditionally owned it— but he did little for the very poorest: blacks, sharecroppers, Dust Bowl refugees. And neither he nor his economists really understood the depression— if they blamed it on anything, they blamed it on rapacious robber barons, which led to some good reforms (e.g. the SEC) but did little to address the deflationary crisis. As a result many of the New Deal measures were really stopgaps: finding government work for a few million unemployed, paying farmers to produce less.

Leuchtenburg points out that as farmers improved their lot— farm income quadrupled during the New Deal— they became more conservative. In many ways this has happened to the country as a whole since FDR's time. People no longer remember the situation Roosevelt inherited and which modern liberalism was invented to solve:

(Leuchtenburg covers only the buildup to the war, which is enough to show that modern complaints about the slowness of Roosevelt's response to the Nazi and Japanese threat are nothing but useless hindsight. The country, left and right, was rabidly, stubbornly isolationist. Roosevelt pushed where he could; but if this supreme persuader couldn't get the nation interested in fighting earlier, no one could.)

| |

|

Stephenson's apparent politics, however, have gone from liberal (Zodiac) to libertarian or possibly anti-libertarian (Snow Crash) to conservative. Snow Crash showed a world disintegrated into a thousand non-contiguous entities, with everyone pretty much doing what they want, or at least what they can afford. The Diamond Age is more or less a continuation of that world (a character from Snow Crash even makes an unexpected appearance), and it postulates a liberating technology (nanotech and matter compilers); but it puts hierarchy, moralism, and even something resembling nation-states back in vogue. The two main powers, the Neo-Victorians and the Confucians, both consider the entire moral atmosphere of the 20th century to be lawless and decadent, and have purposely embraced the morality of a previous age.

I find this a bit jaw-dropping; it's as if he's suddenly started ranting about the mid-20C dictatorship of the UN. Not trying to be diplomatic: "moral relativism" is propaganda; it's the invention of people who don't understand and don't want to understand that people can disagree on morality. Differing moralities consider each other immoral. Why is this hard to understand? It's not that liberals or Marxists (these are, please note, two different creatures) want to erase moral distinctions. They are absolutely brimming with moral judgments of their own. They simply don't agree with some of the moral judgments of conservatives.

Fortunately, Stephenson retains some moral complexity, and if the book praises conservativism, it's also the story of how to undermine it. The main thread of the story is about, of all things, how to educate young girls in subversion. Stephenson recognizes the essential problem of conservativism, which is that no matter how wise your morality and how well-considered your social system, those who grow up in it passively, unquestioningly, will degrade it through incomprehension, apathy, or a sense of entitlement. Society, including conservative society, needs subversives— people who think for themselves. They may end up rejecting their society, or they may rethink it, but it won't progress without them.

Science fiction is actually fairly fond of the past. I suspect it makes for better fiction than prediction. We know the past, so it gives us a leg up to apply our knowledge to the future— a wholly alien society, by contrast, is much harder to bring alive. But I can't think of any successful real-world attempt to reproduce an earlier era, and I doubt that this record will change.

| |

|

Sharansky's position is that "the way to real peace in the Middle East should be paved with democratic reforms." By this he means reforms among the Palestinians. He thinks that Arafat only retained power by fear, and that the majority of Palestinians disliked him. Apparently, in free elections, they would be happy to make peace with Israel.

On the one hand I'm glad to see anyone who really believes in democracy, and hopes to see it in the Arab world. But how can someone be so unable to apply his own words to his own society? Who is to blame for Palestine not being a democracy? The West Bank and Gaza have been under Israeli rule for 38 years— more than a generation, longer than the British ruled Palestine. Israel was completely content to maintain this territory in grinding poverty, to exclude it entirely from any hope of citizenship, to colonize and expropriate whatever land it wanted, and finally to hand over the remainder to what it hoped would be a grateful despot.

After all that, it's really a bit much to blame the Palestinians for somehow not being a Jeffersonian light to the nations.

(Not that this lets the Palestinians off the hook; Arafat never rose above the mentality of a gang leader, and couldn't even succeed at that level. And the terrorists have destroyed any hope of an Oslo-like process of slow progress toward normalization.)

The absolute worst course for one who believes in democracy is to push democratization above all else— to make it a condition for dialogue. New democracies are fragile, and if they're accompanied by corruption and economic collapse, democracy itself is thrown into disrepute. We should have learned this 75 years ago, with the failure of Weimar Germany.

Frankly, I think there's only one solution to the impasse in the Middle East: make the Palestinians rich. People who can see their lives improving can be generous to former enemies. More desperation and poverty will only impel the Palestinians to more bad choices.

| |

|

Most of the discussion surrounding [Natan] Sharansky's book has focused on what he calls "the town square test" for free societies. Here's how Sharansky defines the test, which Condoleezza Rice endorsed during her Senate confirmation hearings: "Can a person walk into the middle of the town square and express his or her views without fear of arrest, imprisonment, or physical harm?" Sharansky uses this test to devise the central policy recommendation in The Case for Democracy: He wants to "turn a government's preservation of the right to dissent— the town square test— into the standard of international legitimacy," and he recommends sanctions and pariah status for the nations that fail it.David Neiwert today in his blog:

In Colorado, a woman was threatened with arrest by a Denver police sergeant for sporting a bumper sticker on her car that read, "Fuck Bush".Wonder if the sergeant voted for Dick Cheney?..."He said, 'You need to take off those stickers because it's profanity and it's against the law to have profanity on your truck,' " Bates said. "Then he said, 'If you ever show up here again, I'm going to make you take those stickers off and arrest you. Never come back into that area.' "

[A reporter] who had followed the officer into the store, said Karasek wrote down the woman's license-plate number and then told her: "You take those bumper stickers off or I will come and find you and I will arrest you."

...Reached late Monday, City Attorney Cole Finnegan said he didn't believe there were any city ordinances against displaying a profane bumper sticker.

| |

|

We all have a vision of living in big isolated house on acres of woods because, I suspect, it's in our genes: we're primates, and we feel most comfortable in a savannah. But for minimal intrusion on the environment, there's nothing like cities. They take up less space; they allow us to walk to places; they're dense enough that things like recycling and public transit become realistic options.

Now, I hope that you, as a reader of zompist.com, find this little tidbit provocative, and rethink a little bit of your worldview as a result. Because that's the real point here: no one is really rational unless they are frequently making such adjustments, unless they look at how things actually work and find that, as it turns out, it's different from their preconceptions.

Politics ought to be the same way: we try something out and, if it doesn't work, we fix it. But politics is actually hostile to this sort of adjustment.

Politics these days, left and right, is driven by the bullet-pointed scare letter. Organizations send out mailings to dun the contributors, and in order to generate the requisite outrage, they tell anecdotes about the Evil Things the opposition is up to.

Bullet points are a lousy way to learn about the world, because they can always be generated. There's always some nutcase out there who'll generate an absurd lawsuit or propose the outrageous legislation or make the intolerable remark or commit a heinous crime. The bullet points tell you nothing about how prevalent or important such behavior is; they just raise the blood pressure.

It works— it's effective fundraising technique— but it leads to bitter, hardened politics. There's no room for learning what's really true and modifying one's views accordingly— especially because it's usually one's opponents that point out these little problems, and they are, you know, Evil.