As a supplement to my pages on what went wrong in the 20th century, and why libertarianism is bad, I thought I’d write about the economic system that works the best for the most people: liberalism.

I also have a page on the morality of liberalism. But this page will focus on practical measures.

Much of our political quagmire comes because politics takes the place once occupied by religion: people make creeds, seek converts, demonize the enemy, start wars, out of the fervency of their beliefs. And you may need that faithlike devotion if you want to fight totalitarians or end segregation. But it’s not appropriate for the basic questions of how to run a democracy. What systems actually work to measurably improve the lives of most people? We can only find out by seeing how they work in the world.

‒Mark Rosenfelder, September 2012

For European readers, American liberalism is close to (but mostly to the right of) social democracy. (It’s not the so-called Washington Consensus of Reagan and Thatcher, which is called libéralisme in France at least.) It’s capitalism regulated by government, plus a substantial safety net.

Now, obviously there were Republican presidents in the liberal period‒ Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford. But they were restrained by a Democratic Congress, and largely governed as liberals anyway. (Nixon created the EPA, expanded affirmative action, and raised social spending from 28% to 40% of the budget‒ raising it for the first time above defense spending .) And there have been Democratic presidents in the Reagan era‒ Clinton and Obama. But with the single exception of health care, they were mostly occupied with cleaning up the mess left by Republican presidents, and they were greatly restrained by Republicans in Congress; they did little to undo the rightward shift in politics. So it’s fair to compare the fifty years starting with Roosevelt to the thirty years starting with Reagan.

Studying broad periods also evens out the business cycle and the small-scale events that dominate the daily newspaper. Particular events can dominate a single presidency (e.g. you can hardly discuss Jimmy Carter without focusing on the fourfold rise in the price of oil), but looking at decades-long periods is a fair test of a political-economic system.

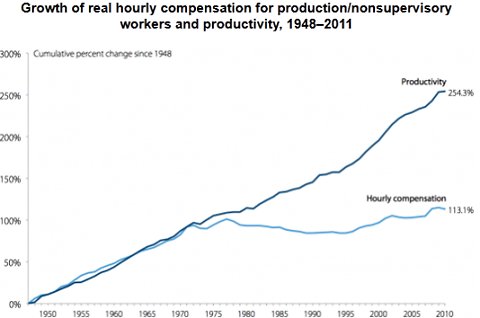

(The economic definition of productivity is useful precisely because of its broadness and simplicity. It covers technological progress, capital investment, access to new resources or markets, organizational changes, even social changes like decreased corruption or a movement of women into the workplace. For the purposes of examining social progress, the importance of the number is that if it ain’t rising, we’re doing it wrong. There’s no iron law that makes wages go up over time. The basic mistake made by the USSR is that merely redistributing income at best makes for a stagnant and fairly poor society. Wages will keep rising only if productivity is rising.)

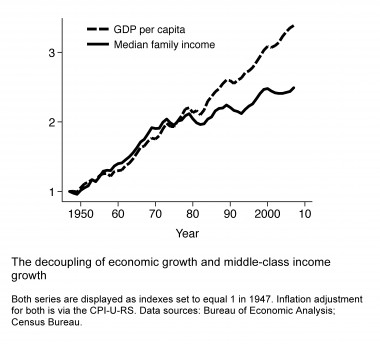

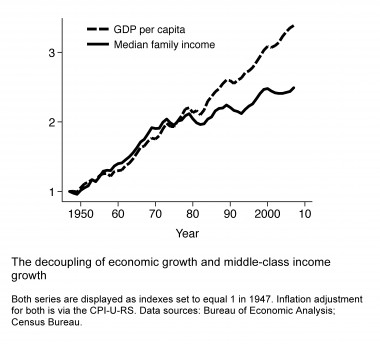

Before getting into the big bend in the income line, let me emphasize that productivity has risen at about the same rate over our entire period. I’d love to report that liberalism increases productivity, but I can’t. But more imporantly, liberalism doesn’t decrease productivity. That means that various conservative charges‒ that economic progress is stifled by high tax rates, or by unions, or by large government, or by “regulation”, or by health insurance‒ just aren’t true.

Now, let’s look at that dividing line, at 1980.

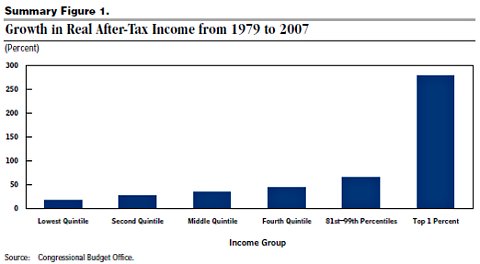

This is even more striking when we look directly at incomes for different quintiles:

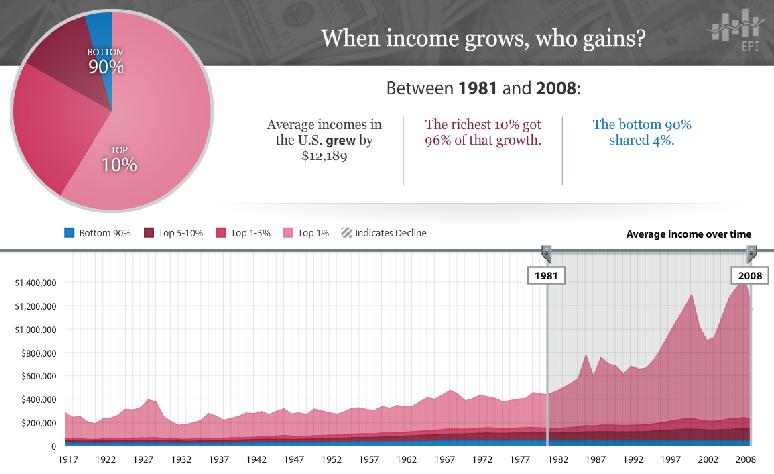

The Occupy Wall Street movement hasn’t taken the world by storm, but it’s given us a useful social category to think about: the 1%. These people are doing very well indeed: their share of national income was 8% in 1979, and more than doubled to 17% by 2007.

We need to be very clear on what this “income share” business means. It doesn’t just mean that they made twice as much money. Productivity is rising, so the total wealth of the country is rising; under liberalism, if productivity has gone up 50% since 1980, which is what the first graph tells us, then their incomes would go up 50% too. But they did much better than that: their incomes went up 300%.

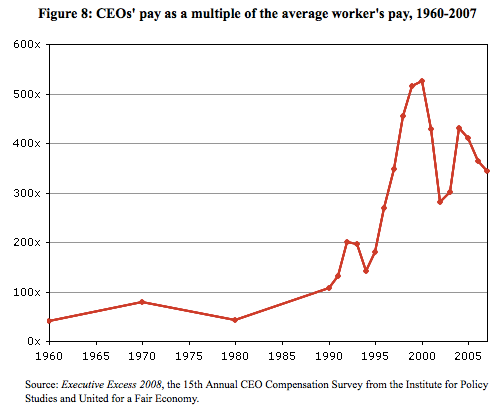

And that’s just looking at the 1%, not the even smaller percentage that’s doing even better. In the 1960-85 period, CEOs made about 50 times the salary of the average worker. In the ’90s they made 500 times the average worker’s salary‒ that is, their relative incomes went up 1000%. (The recession clawed it down to 350 times.)

By the way, the picture looks the same even if we look at total compensation (that is, including nonwage benefits) rather than wages:

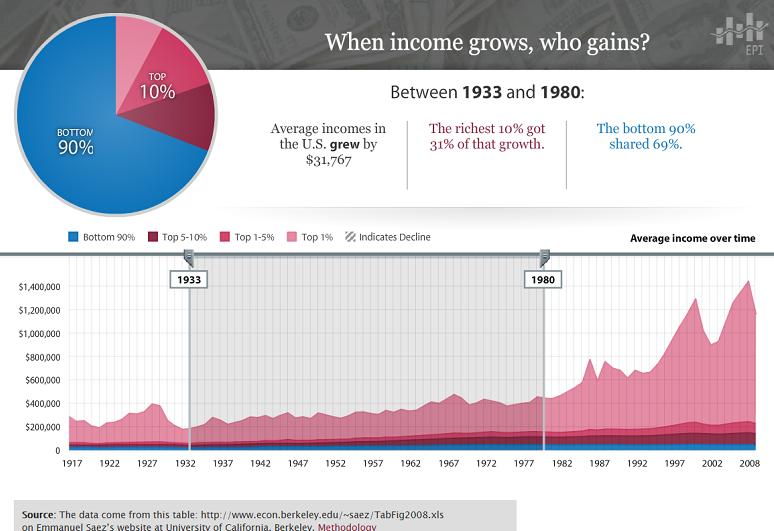

Here’s a closer look at the income story, from this neat interactive chart. First, under liberalism:

Now, under plutocracy:

It doesn’t take a stratospheric income to make the 10%‒ as of 2010, it took about $114,000 a year. People at that level don’t think of themselves as rich; they think of themselves as middle class. (I certainly did when my income was close to that level.)

And a key fact about our system is that this tier is doing all right; in fact, since 1980 it’s pretty much received its fair share of productivity gains. The top 10% is also, of course, little affected by 8% unemployment. This is undoubtedly the key factor in our political inertia. Because they’re doing all right, the top 10%‒ which includes the leadership of both parties‒ doesn’t see any great problem.

Why do the 90% stand for this? We’ll get back to this question below, but for now I’ll note that probably most people don’t realize what’s happening. The country doesn’t look all that different; there’s still social spending and politicians gravely talk about the problems of ordinary people. That is, there’s a pretense that the liberal society is still in effect. The quiet change to plutocracy is rarely discussed, and if it is it’s presented as an intractable problem that probably requires punishing ordinary people, not as something that was solved for a fifty-year period.

In the liberal period, poverty declined from 30% of the population to under 10%. Thus the idea that the US was a middle class country, one where the average person was doing well. This was almost unprecedented in history! The middle class had always been a minority.

Under plutocracy, efforts to reduce poverty ended. And now poverty is rising again; it’s up to 15%.

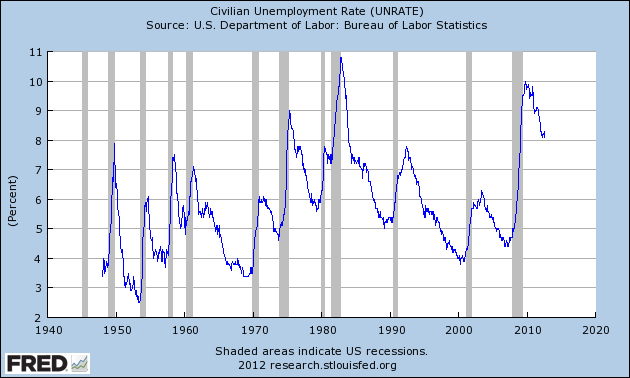

Laissez-faire can produce big booms, and it did so in the ’20s. Then it blew up, spectacularly. The stock market crashed, then the economy. And then, for four years, pretty much nothing happened: the Very Serious People of the time thought that the economy needed to be “liquidated”, so they just let it spiral into misery. Unemployment reached 25%; the banking system entirely disintegrated.

FDR started pumping money into the economy, and things got better. In 1937 he made the mistake of listening to the Very Serious People and cut back spending; the economy went into a recession and much of the progress made was lost. (This wasn’t mature liberalism‒ FDR was improvising much of the time, and not everything he did actually helped.)

See also my reviews of Frederick Lewis Allen’s Only Yesterday and William Leuchtenberg’s Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.

As everyone knows, World War II came along and the economy soared.

Some folks seem to think that WWII doesn’t count, somehow, because it was a war. It sure was, but spending is spending. Of course, it gave great political cover; it was the perfect excuse to increase government spending 800%. Plus, as a bonus, we defeated the Nazis! On the other hand, we might have needed far less spending if we weren’t essentially throwing most of that money away. Buying useful things, like roads and universities and health care and solar energy and spaceships, should be better stimulus than fighting wars.

Does that mean that government spending is always good? Of course not. It’s good in a depression, and that includes the crisis the Bush administration gave us in 2008. Keynes told us to cut back spending in good times, and ramp it up in bad times. But that gets us into the next subject: debt.

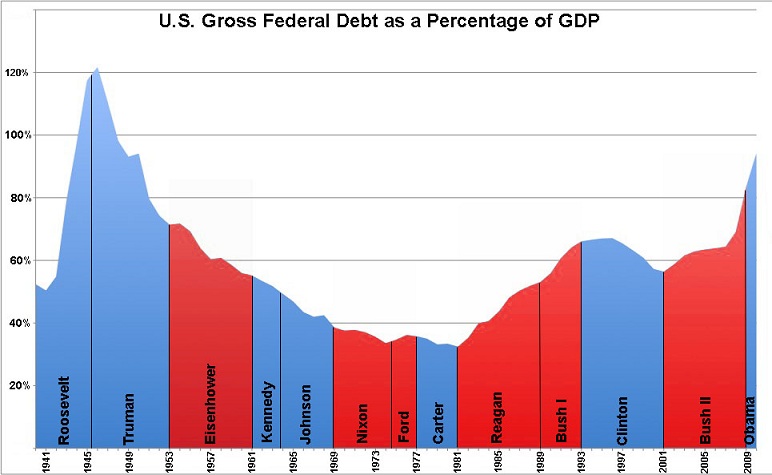

No. Conservatives like to focus on total debt (when Democrats are in power) because it’s scarier; but we’re constantly increasing our wealth. The economy is twelve times the size it was in 1929; we can afford more debt. The important measure is debt as a percentage of GDP. (That’s the equivalent of comparing your mortgage to your current income.) Here it is (from Wikipedia):

Second thing to notice: by contrast, plutocracy is spendthrift. Reagan, Bush I, and Bush II exploded the debt. Between them, they erased thirty years of progress. Clinton undid some of the damage‒ again, liberals believe in actually governing responsibly, so it was the right thing to do and he did it. Obama inherited the worst crisis since Hoover’s; most of the debt increase since he took office is due to automatic extensions of the safety net, plus stimulus tax cuts‒ and it’s been more than offset by misguided cuts in state government spending. Right-wingers fantasize that Obama has greatly expanded government, but it’s a myth.

What was the actual mechanism? Obviously it wasn’t just electing Ronnie. Several things went together:

There had always been opposition to the New Deal, but it was marginal. A key element was the movement of Southern whites from the Democrats to the Republicans, largely due to opposition to civil rights. As we’ve seen, Nixon expanded the safety net, so he certainly wasn’t anti-black. But the anger of Wallace voters in 1968 must have been educational. Picking up southern whites removed a key element of FDR’s coalition and paved the way for Reaganism.

Obviously, a lot of this was done using smoke and mirrors. Though Republicans haven’t been coy about favoring the rich, Republican candidates don’t campaign on the slogan “Nothing for the majority; everything for the super-rich.” They have to distract the electorate with cultural issues, and pretend that their policies are good for everyone.

Now, in 1980, they could claim ignorance: maybe Reaganism would work, maybe tax cuts really would increase tax revenue! Maybe this next perpetual motion machine will really work! But we’ve been drinking the magic kool-aid for thirty years now, and it’s not working. So the program now has to be maintained by pure denial.

For much more detail on how the 1933-80 period worked and how it was different from what came before and after, see Paul Krugman’s The Conscience of a Liberal.

Oh, and they want to end health insurance for the elderly and those newly insured by Obamacare, repeal financial regulation, and maybe start a new war on Iran.

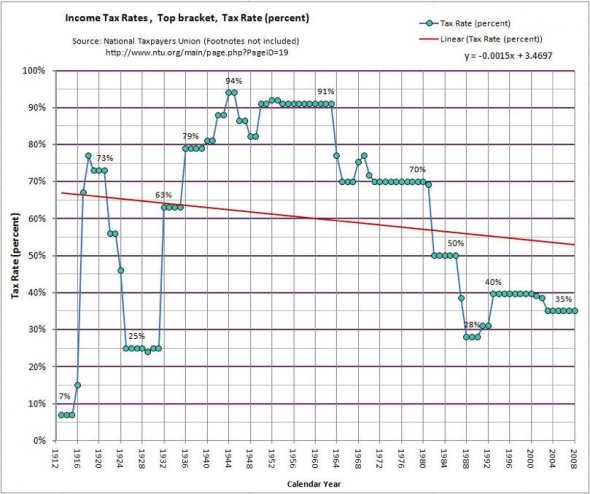

To Republicans, it’s always 1968, with taxes sky-high and hippies revolting in the streets. Whatever the situation, their answer is always to lower taxes on the rich. But we’ve been doing that since the sixties, and it never helps the rest of us. Quite the opposite; the rest of us are stagnating or worse off.

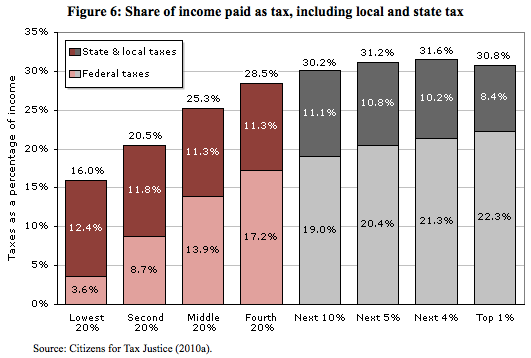

When we talk about taxes, by the way, don’t get snowed by the GOP preference to talk only about the federal income tax, which is highly progressive. For the poor, state and local taxes are a much bigger bite:

Common sense suggests that when you reduce government revenue, government revenue will go down. And it’s right! Over Bush’s term, as a percentage of GDP, federal revenue dropped from 20.5% to 17.5%. (One consie trick is to count dollars instead. But revenue in dollars will go up due to population growth and productivity growth; you have to look at the percentages, instead.)

Ironically, one of Bush’s justifications at the time was precisely to reduce the budget surplus. That was the conservative doctrine of 2001: Alan Greenspan gravely informed Congress of the terrible dangers of reducing the debt. They don’t really care about the debt; all they care about is taxes.

As for job creation, over the eight years of Bush II, 2.6 million jobs were created. Over Clinton’s presidency the figure was 22.7 million, nearly ten times larger. (And that actually gives too much credit to Bush, as jobs were hemorraging in the first months of Obama’s term, delayed casualties of Bush’s blow to the economy.)

Perhaps confusingly, to get us out of our present crisis, Keynesian economists advocate... tax cuts, among other things. This isn’t a contradiction; we’re in a liquidity trap, when the economy can’t be jumpstarted simply by lowering interest rates (because they’re already effectively zero). This isn’t the sort of recession we’re used to in the post-WWII era, though it’s very similar to the Great Depression. Tax cuts are a cheap stimulus right now, because the cost of borrowing is very low. However, tax cuts can’t be the only solution‒ they do very little for the unemployed and the poor, for instance. They need money and jobs, not tax cuts.

This is why Bob Deitrick and Lew Goldfarb’s book Bulls, Bears, and the Ballot Box is so interesting. They compare the economy under Republican and Democratic presidents from 1929 to 2008‒ as it happens, that works out to 40 years each. Their results are stunning.

Now, the Republican numbers are weakened because they include Herbert Hoover. However, they aren’t improved much if you remove Hoover and, in compensation, Jimmy Carter. And arguably, it’s completely fair to include Hoover when current Republican doctrine is precisely to repeal every element of the New Deal.

Under Democrats Under Republicans Avg. annual stock market return 9.60% 0.58% Avg. annual change in GDP per capita 3.48% 0.50% Avg. annual change in national debt per capita 0.83% 3.90% Percent of months in recession 8.22% 29.59% Avg. annual change in corporate after tax profit 4.53% -11.65% Avg. annual trade balance -34.38b -174.10b

The model of a super-rich class that takes in most of the wealth has been tried. You can see it today in most of the Third World. And, contrary to what conservatives claim, the wealth doesn’t trickle down. The bulk of the population stays poor, and the situation maintains itself for centuries.

Suppose you want to sell automobiles, or iPads, or houses. Where do you think you’ll make more money, the US or the similarly populous Indonesia?

If you’re hesitating, consider a couple quick facts:

What if the US had stayed at the 1900 poverty rate of 40%? That is, what if 80 million people more Americans had an income of $10,000 rather than the present average of $48,000? The economy would take an immediate hit of $3 trillion. (Really much more than that, because of multiplier effects. If 80 million people saw their income plummet, they’d spend much less, so retailers’ incomes would crash, leading to even more misery.)

Indonesia USA GDP (total) $845 billion $15 trillion GDP per capita $3500 $48,000

As we saw above, from 1933 to 1980 the average income went up $31,767, of which 69% went to the bottom 90%. To simplify things for these rough calculations, let’s pretend all the ninety-percenters were paid the same. In that case, their incomes increased by $21,284.

In the 1981-2008 period, the 90% got just 4% of the pie: their incomes went up $488.

If the income distribution had stayed the same as in the liberal era, their incomes would have gone up $8,167. That’s a lot more automobiles, iPads, or houses sold.

Perhaps it doesn't matter, because no matter who gets the income, they spend it and it becomes consumption? No; as economist Joseph Stiglitz has shown, the middle class spends most of its income, while the rich save 15-25% of it. So giving money to the middle class is the better way to increase consumption. And giving money to the rich leads to more investment, which is liable to produce a speculative boom and crash.

By now it’s clear that communism isn’t an alternative. Capitalism does better than communism, for both rich and poor. This was of course not obvious a priori‒ for all anyone knew in 1932, Marx and Orwell were right, and capitalism was too stupid to thrive. In the early part of the 20th century, in fact, there were times when the USSR was doing better‒ it didn’t suffer the Great Depression, for one thing. But it’s now clear that this was the one-time effect of a transition from agricultural to industrial production. Once it was done, the USSR stagnated. China didn’t prosper until it effectively abandoned communism.

Dictatorships in general are also a bad idea, from a purely pragmatic point of view: either they strangle the economy with crony capitalism, or they destroy it with war.

From my point of view, there’s no great difference between American liberalism and European or Japanese social democracy. Other countries often do a better job at the social part‒ our Social Security is well run, but we tend to half-ass the rest of the safety net. For awhile conservatives thought that the safety net was slowing Europe down, but that’s not the case. The irony is that Europe is now being mismanaged on conservative principles: the Europeans’ solution to a depressed economy is to put people out of work, tighten money, and lower spending. So they’re implementing Hooverism right now, and it’s working about as well as it did for Hoover. (Hint: not well.)

It’s true that a very generous welfare state seems to reduce GDP per capita; e.g. the ratio of French to US GDP per capita is .731 (as of 2008). But if you look at GDP per hour worked, the ratio is .988. That is, French workers are just as productive as Americans; they just work fewer hours. And that’s basically a social choice: they start work later, they retire earlier, and they have longer vacations. That’s just a different set of choices on what to do with productivity gains. (And it’s not like we’re at the opposite end of the scale; the five-day week and the eight-hour day are 19th century innovations.)

Is there an untested alternative? I hope so! The modern economy is the culmination of centuries of experimentation and revolution, and I’m sure we’ll come up with something better. Heck, I’ve written an sf novel about it. On the other hand, the more radical your proposed changes, the less likely they are to a) work, and b) convince me to vote for you. Plus, if your new idea is “laissez-fair plus marijuana and maybe the Singularity”, don’t bother.

Of course we don’t think about violent revolution in the US, but why not? It happened in some very advanced countries (Germany, Italy), and there were some very restless people in the Depression and in the 1960s. Very simply, liberalism calmed them down‒ because people could see that they were getting better off. What if the conservatives succeed in impoverishing the middle class? How long will people buy into a system that’s operated only for the benefit of the Romneys and Galts and Gekkos?

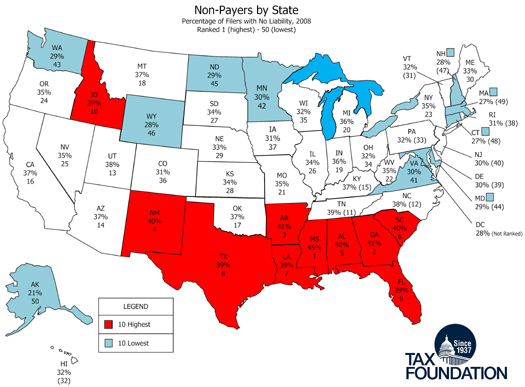

You can’t get much clearer than that: the Presidential nominee for the Republicans makes it completely clear that he is only concerned for that 53% who happen to pay federal taxes. That’s immoral, un-Christian, and disgusting.

But that’s just morality. Just as appalling is his use of this stale consie trope to tell his big lie‒ that Obama voters are irresponsible.

Let’s look at who pays federal taxes‒ and why not.

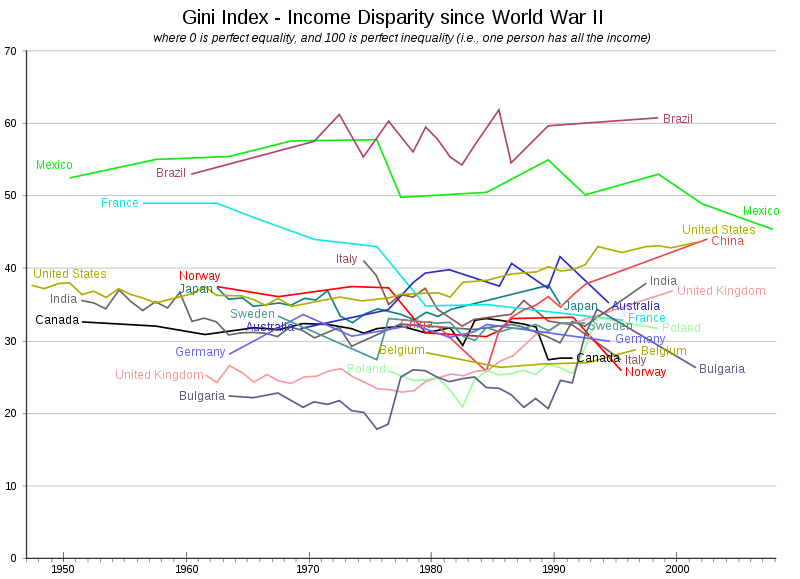

No, because in that case we'd see the trend across all modern economies, and we don’t. Here's a chart (from Wikipedia) of the Gini coefficient, which is a measure of inequality.

It’s a little cluttered, but just follow the colors. The top of the chart represents greater inequality.

But Germany, Japan, Canada, and Australia are all pretty stable, and France’s inequality has plummeted.

Rising inequality is not inevitable. It’s a social choice the US and UK have made.

The question is not “Do the rich perform some function for the rest of us?” but “Did they suddenly perform this function ten times better, so they deserve ten times more than they used to get, and the 90% deserve nothing at all?” There’s simply no metric that justifies this pay increase, nor the marginalization of the middle class.

And you know, things did get a little crazy in the ’60s. Some of it was defensible, much of it wasn’t. Some of the raucousness is because asking politely for more rights just doesn’t work. It’s been tried, and it gets ignored.

But again, it’s irrelevant to the liberalism-vs-plutocracy debate. It’s not 1968 any more; the hippies all cut their hair and stopped talking about Chairman Mao, which didn’t make it with anyone anyhow. Ironically, the young people of the ’60s are now likely Romney voters.

One, we’re looking at actual track records here. And just as I don’t buy libertarian fantasies, I don’t buy socialist fantasies. The actual attempts at building non-capitalist societies have been, at best, stagnant and inefficient, and at worst genocidal. If you want a really radical reform, you’d better have a really good plan to avoid the failures of your predecessors.

Two, I’m sympathetic to many left-wing complaints about liberalism (and, even more so, to complaints about liberal politicians). But the main obstacle to a more progressive society is not liberals, it’s conservatives. The brute fact is that many progressive positions appeal to no more than 25% or so of the American public. That means they don’t win elections. There are things I wish Democrats would champion more, but even if they were all angels that wouldn’t give us the House or get rid of the filibuster.

The Republican Party is pretty clear on its preference: much more important than general prosperity is low taxes for the rich. I think their morality is deplorable, but I can’t fault their understanding of their self-interest. But whatever your bigger value is, the first question is, why should anyone else agree with you? Why should the 90% go along with a system that marginalizes them, when there is an alternative that doesn’t? Or if you think (erroneously) that liberalism is anti-religion, well, why should the non-religious help build your spiritual utopia?

The other important question is, why are you so sure that your good is incompatible with social justice and a prosperous capitalist society? The rich and the religous didn’t die off under liberalism, quite the reverse. The rich got richer; Evangelicalism became dominant. Look at what actually happened, not at the fear-mongering in the latest fundraising letter.

Besides, whatever Republican leaders have in their hearts, they say that their policies will produce more prosperity, more jobs, less debt. It's fair, indeed essential, to look at whether their claims are true.

I hope this page will help. Liberals don’t need to apologize for their vision of how American society should work. Liberalism saved American capitalism and democracy, defeated Naziism, created a prosperous middle class, and benefitted every sector of society, from the back streets to Wall Street.