| September 2015 |

|

| G. Willow Wilson & Adrian Alphona: Ms. Marvel | |

You wouldn't think Marvel has to skimp on superhero names, but apparently there have been four different Ms. Marvels. This is the current one, started in 2013, civilian identity Kamala Khan.

You wouldn't think Marvel has to skimp on superhero names, but apparently there have been four different Ms. Marvels. This is the current one, started in 2013, civilian identity Kamala Khan.

Kamala is a Pakistani-American teenager living in Jersey City, and acquires shape-shifting and healing powers more or less by accident— at least from her perspective; at a party, she wanders into some green gas. We've all been to some weird parties. Later on it's explained that she's genetically Inhuman. Oh lord, what are Inhumans? Without falling too far into the rabbit hole of Marvel lore, the Inhumans are humans genetically mutated by the alien Kree, because reasons. In practice this means Kamala has some powerful allies. We'll get back to that.

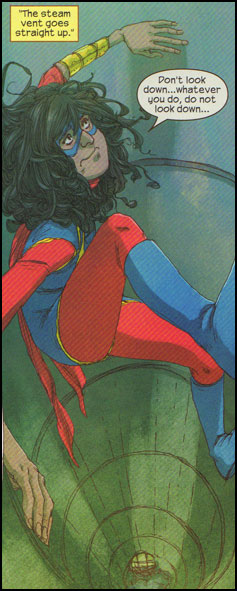

The tone of Ms. Marvel is light, even comic. Kamala is as confused about her new powers as anyone would be, and struggles to learn how to use them. (They basically let her grow or shrink, and this can be applied to body parts, so she can create enormous fists, or long legs, or shrink to ant-size to get into a machine.) Her major obstacle, beyond the supervillains, is her family: she doesn't tell them about her powers, so she has to sneak out at night to use them. This doesn't always go well, and her concerned parents consider sending her back to Pakistan or— even more mortifying— for extra moral instruction at the local mosque.

The comedy of manners part of the title is completely charming. Kamala's parents and the mosque teachers are presented as uptight and overprotective, but there's no bitterness in the portrait— at root they're concerned parents, and immigrants who don't entirely understand the culture they're joining. When she's with her friends, Kamala is entirely Americanized; at home she's beset by contradictory impulses. And that's before she gets the superpowers.

As for the superhero stuff… I have to complain a bit. Not about about Wilson, but about the genre. Like an anti-gift from Fate, the new Ms. Marvel gets a minor supervillain of her own. The details are tiresome: his name is the Inventor, he has a lair, he has a bird head, he builds robots that Kamala has to beat up, he steals street kids and uses them in a way which makes no sense whatsoever. There may be life in this old formula, but when a hundred comics are trying to find it every month, a new angle is vanishingly rare.

Wilson does it better than most, perhaps— I liked a sequence where Kamala fights alongside Wolverine. Kamala begins by fangirling him— and mentioning the fanfic she's written about him— but they end up saving each other's asses and Wolverine treats her as a peer, despite the fanfic. And Wilson avoids the whole grimdark thing: Kamala spends the whole first TPB, for instance, barely knowing what she's doing, and as concerned with finding a good place to change into her outfit as she is with tracking down the Inventor. And in volume 2, she makes a useful friend— Lockjaw, the Inhumans' huge teleporting dog— but that brings a serious problem: her parents don't let her keep him in the house, because dogs are unclean.

The book most reminds me of Ranma 1/2. There's a strong manga influence on Ms. Marvel, but I think it could have used more: the lightness and silliness of Ranma is a good model. Most of the time Ranma's adversaries are just his classmates and frenemies, not costumed psycho agents of Eeeevil. It would be fun to see a teen supervillain as unsure of himself as Kamala is.

The standard interpretation of Marvel's mutants is that they are symbols of puberty, or adolescent alienation, or gayness. In theory this allows adventure stories that connect to various types of human experience (the vagueness is part of the allure: however you feel you're different, the mutants reflect it). And once this resonance is built up, the supervillain angle comes in to remove it.

In volume 2, the Inventor comes by Kamala's school and trashes it. It's what supervillains do, of course. But adolescent angst doesn't trash your school. This is the sort of thing that happens in war zones or terrorist attacks. It doesn't make sense to me, after that, to keep the old trope of the secret identity. If Kamala keeps her powers secret from her parents and teachers, she's not only living a dangerous double life, she's actually seriously endangering them.

Still, again, it's not Wilson's fault, it's the genre's. I just have much less patience for supervillains than I used to— the best part of any superhero book tends to be the parts where they're absent. And that stuff in Ms. Marvel is unusual and fun.

It's a pretty good urban fantasy, perhaps at its best when the plot is whirling back and forth and you don't quite know what's going on. Blythe is an interesting character, often confused or terrified, but not infrequently capable of intuitively doing the right thing. Unfortunately she's not well served by the artist (M.K. Perker). The art is adequate, but for fantasy you really need something more than that.

Wilson is a Muslim, and though this didn't come up in Air, it was unusual to have Blythe's love interest be Middle Eastern, and her opponents scary white men.

| Richard McGuire: Here | |

A quarter century ago, Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly put out Raw-- a highbrow mixture of underground cartoonists and French BDs where, in general, the id was fully on display. In Vol. 2 No. 1 (1989) six pages were devoted to a little story called “Here”, by Richard McGuire, which looked a little too clean and cool for its surroundings. It was also the most mind-bending piece in the whole 200-page issue.

Every image of “Here” depicted the same scene, from the same viewpoint. But that wasn't the clever bit. The clever bit was that not all the panels showed that scene in the same year. In fact, after a few establishing panels, windows within each panel showed different years. The entire six pages depicted-- out of order-- a story ranging from 5 billion BC to the year 2033.

Most of the story was concentrated around a single lifetime, from birth (1957) to death (2027). It was a fascinating look at a place, a lifetime, at how moments could be connected not just in linear sequence but by theme: similar events occurring in the same place; a woman's complaint about cleaning repeated over the years; a tree growing; echoes of action or dialog.

Oh, here. Here's “Here”. Just go read it. Six pages, light as a feather and dense like lead. It refrains from any sort of comment, and somehow seems to be about everything: time, space, life, humanity. It was just amazing that you could do this in comics.

Now, McGuire has produced Here, a version of the same idea, but 300 pages long, and in color.

Before you read the rest of this page, you should open a new tab, order the book, and read it. It expands the original idea, playing with the resonances of time and space, and the color version is spectacular. Plus the corner of the room is in the crease of the book, which is a neat iconic idea: the opened book echoes the shape of the room.

Better yet, get the iPad version, where reportedly you can view the book in multiple ways, or trace a particular thread chronologically.

OK, now that we've read it, I'm going to say: it's neat and I like it, but the 300-page version doesn't blow the mind at 50 times the rate of the 6-page story. A lot of what McGuire does here, he already did in the previous version. It's a neat way to play with the medium, but it's definitely in experimental mode, and in such things the emotional temperature tends to be low.

There's a set of family pictures that look a lot like real family photographs, and from articles on the book, it turns out they are real photographs from McGuire's family. Likewise, a bit that seems like rather a stretch-- a connection to Ben Franklin-- turns out to be literal truth: McGuire's childhood home in New Jersey was across the street from Ben Franklin's son's house. Similarly, a visit from the local archeological society (they want to dig up the back yard for Indian bones) really happened.

The thing is, when you have to read news stories about the book to understand the connections, that's probably a sign that the artistic method is a little too detached. The book plays delightfully with its concept, but it doesn't cohere as a story. There are recurring characters but after two readings I couldn't tell you who they are.

Oops, I should learn to write these things with the positive stuff at the end. The 6-pager did seem short-- more like a proof of concept. The book takes it slow, runs the idea through all its variations, is more careful about history (it's a nice touch that the Native Americans speak an actual Algonquian language), it's full of quirky juxtapositions, and it's gorgeous to flip through. (In fact, I suspect Here is one of a small class of books that you should keep on your desk for a few months after you read it, just to browse through on a whim. I think it would repay a deep study.)