| |

|

There was some conversation afterward, by the TV, which was lost on me... mainly between Lica and his mother, with some comments from his sister, and only a few from Dad. After awhile I took some pictures-- of them, of the house, and of any stray X-rays remaining from airport security checks.

There was some conversation afterward, by the TV, which was lost on me... mainly between Lica and his mother, with some comments from his sister, and only a few from Dad. After awhile I took some pictures-- of them, of the house, and of any stray X-rays remaining from airport security checks.

After this Lica took a long phone call from Shirley, and his mother took the opportunity to have a long conversation with me in Portuguese. This must have taken much patience on her part, since she had to speak deliberately, repeat often, struggle through my laborious sentences, and resort on occasion to English, which she knows a little. (Lica's father studied for 3 years in Texas, and reads English and French, but didn't want to speak in either one.) She asked about my family; when we got to my nieces we talked about the difficulty of raising kids nowadays, amid drugs, divorce, and declining morals, which led to the parlous state of the world in general. It was not possible, I suppose, to exchange anything but platitudes, given the state of my Portuguese, but it was still satisfying, and this without any help from Lica.

Finally she asked why you sometimes pronounce I as [aj], as in Michael, and sometimes as [I], as in pin, and said no one had ever answered this question. Well, this was a challenge, and I launched into a discussion of the Great Vowel Shift (a Grande Mudança dos Vogais), attempting to show that Old English i: and i were much more similar, likewise e: (keep = [ke:p]) and e (kept = [kept]), till the Great Vowel Shift moved all the vowels up. I don't know whether this really helped, but it was certainly an experience for both of us.

I tried a few sentences with Sr. T-- M--, fairly successfully, eliciting the observation that Texans have to be o melhor em tudo (the best in everything), that he liked the U.S., etc. But if he was taciturn with his own family, it didn't seem he would open up with me.

Then I talked for a couple hours with Lica: about Christianity, Shirley, and Dan M--. Lica disparages divisions between Christians, and Christian crimes, while admiring Christ. He's tempted by 'Spiritism', whose exponent is a Frenchman named, I think, Kardec-- he's reading O Livro dos Espíritos.

More interesting was the talk about Shirley. She's Japanese-Brazilian, and also works at the bank; about a year ago he was madly in love iwth her, and wanted her to live with him. Finally they're living in the same house (in different rooms), but he's cooled off to her, while she's come to love him... an unfortunate story. He's planning to move out in January. He also talked a bit about Dan. [ 2002 note: Dan was the mutual friend who introduced us when Lica visited Chicago the previous year. ] Evidently it wasn't such a happy visit, being complicated by political differences, in turn complicated by Lica's outspokenness; also by the visit of Dan's in-laws at the same time.

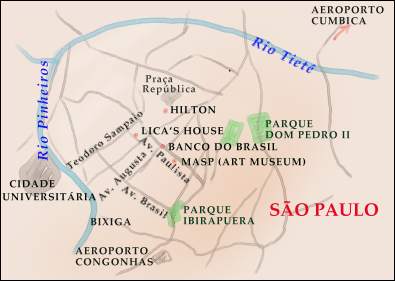

Back in São Paulo, Lica had to work, and took me to his office at the Banco do Brasil, where he works approving (or sometimes disapproving) loans in rural areas. He introduced me to many coworkers, his boss, etc., and to some girls on the 2nd floor who speak a little English. We also said hello to Tereza.

Finally I was sent off to wander São Paulo by myself, taking pictures. I walked up and down Avenida Paulista, stopping for awhile at a café to write. This is the financial district; you can't heave a brick without hitting a bank, or more likely one of its armed security guards. There definitely isn't as much money here as in New York or Paris, but it's undeniably a modern city, with the concrete, bus stops, billboards, welll-dressed people, and cars to prove it; it's far from the 3rd world village one half-expects (and which one would presumably find more of in the Northeast, or Amazônia).

I was exhausted when I got back to the bank--3 hours of walking and I'm a zombie. Lica and I went to the Café Viena again, where he was expecting a friend. I had a frango (chicken, not candy) with a cheese sauce, quite good-- with arroz a grego and fries, and a guaraná. His friend arrived: a woman my age named Sandra, who makes jewelry. She lives in Piracicaba, and was coming to the city to meet clients. She's getting divorced, to Lica's regret (he knows both parties). (Divorce was legalized only 10 years ago. Families, Lica explains, are much closer here. To move away to another city is quite unusual, and to live at home indefinitely is normal if you're not married-- which in turn, to someone like Lica's mother, is a bit odd.) Sandra is quite beautiful, and nice enough, but we could make only a little headway in Portuguese; mostly she talked to Lica.

In the evening we had a quick tour of the Cidade Universitária; the University was moved here after the disturbances in '68, from downtown. Here the students can demonstrate all they want without distrubing anyone else-- they can be sealed off.

I say a tour because Lica had classes, but missed the first and blew off the second. He says he's not a very serious student. In the second class there was a test which, because he hadn't been to the last 3 weeks' classes, he didn't know about and wasn't ready for... instead we wandered around saying hello to people.

The University is absolutely huge-- Lica doesn't know the size, but tens of thousands of students-- the largest university in South America, says he. The building we were in, which has its own bookstore, library, and café, is dedicated to economics, which Lica is studying. In looks and construction the school has the air of an enormous community college-- concrete buildings, utilitarian rooms, plastic seats-- plus the usual college atmospherics-- bulletin boards, posters (a college election is in progress), graffiti on the desks, students with the usual college-age breeziness and noisiness.

Went back home, discussed plans with Lica, arranged for what I'd need during my stay-- key, spare room (conveniently, one roommate just moved out), laundry. All was discussed in tiresome detail-- Lica seeming worried I can't take care of myself. But of course he's been wonderful, and he's even arranged for me to stay with a friend in Rio. It's the ultra-Frommer method.

--Posso retornar quando está lavado?

--Pode.

--Quanto? Uma hora, uma meia-hora?

--Uma hora e meia.

I love the way you can say 'yes' by repeating the verb: Pode. There's a test of your verbs for you. I have corrected one or two of my mistakes above (e.g. é for está) to make myself look better.

Meanwhile I went looking for a place to eat, and settled on the Restaurante Degas. I had veal, with peas and bits of ham in a sauce, plus rice, and wrote. The portions were enormous; I couldn't finish it all. The restaurant could be European-- Italian, maybe; the little storefront cafés/bars are much less attractive, more like Greece maybe. $$$

I went back to Lica's, laundry in hand, and headed out with camera to wander the neighborhood and take pictures. I wished as usual that I had more nerve: I'd like more pictures of stores, people working, etc., and not to worry what people will think if I shoot pictures of everything.

I went back to Lica's, laundry in hand, and headed out with camera to wander the neighborhood and take pictures. I wished as usual that I had more nerve: I'd like more pictures of stores, people working, etc., and not to worry what people will think if I shoot pictures of everything.

The Rua Teodoro Sampaio, which Lica's street (Alves Guimarães) leads into, is full of furniture stores-- very nice stuff, usually, but few customers. I checked out a bookstore and a toy store; the latter had almost all American toys and Brazilian imitations-- commercial-looking stuff, not even Legos or blocks or scientific toys. In another bookstore I bought maps of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro; I'm tired of walking aound too long or in a fog because I don't know where I'm going. Finally I can relate places to the map-- and even know what direction I'm facing. (Lica's place fronts southwest.)

I got back to Lica's about 7, the same time he did. He wanted to rest a bit, so I took pictures of the house and then, as Lica rested more than a bit, I vegged out. We went to the university, caught the last 1/2 hour of one class (macroeconomics), and all of the next (sociology). I listened attentively but picked up very little. In between we had coffee and cheese bread (pãos de queijo) at the cafeteria. Lica talked with some acquaintances; I talked to one a bit in English-- he'd been an AFS student in Delaware.

Back home, Lica showed me his yearbook and pictures from his year in New York. It's evident he had a great year-- friends, attention, side trips-- he was a soccer star, played tennis, went on AFS weekends. And hung out a lot with Dan M--, who looks young; but then he still does.

Shirley asked if we wanted anything to eat-- Lica said no, but I was willing. We had spaghetti and bits of chicken, and talked in a mélange of languages: a little English, a little Portuguese, and mostly French. My Portuguese is probably as good as her English-- very halting-- but we did pretty well in French, so long as I didn't talk too fast. She made some interesting Portuguese-ish errors in French, like Je suis avec soif for "I'm thirsty", on the model of Estou com sêde; also connaisser as a slip for connaître, thinking of conhecer.

Shirley asked if we wanted anything to eat-- Lica said no, but I was willing. We had spaghetti and bits of chicken, and talked in a mélange of languages: a little English, a little Portuguese, and mostly French. My Portuguese is probably as good as her English-- very halting-- but we did pretty well in French, so long as I didn't talk too fast. She made some interesting Portuguese-ish errors in French, like Je suis avec soif for "I'm thirsty", on the model of Estou com sêde; also connaisser as a slip for connaître, thinking of conhecer.

We talked about my movel, about Communism, about movies (she found a lot of symbolism in Blade Runner, some of which went beyond me), about Brazil. The leftists just won most of the local elections held recently; she thinks they need a lot of experience: they've never held power, except a brief stint before a ditadura, and they have more ideas than practice. She's very much into astrology, and there's loads of her astrology books on the front table in the living room. This I can't quite deal with. She seems very serious, but after much conversation, she warmed up considerably. She insisted on using vous, however, and eventually I switched from tu to vous-- l'éducation trop livresque, je me doute, since she used você in Portuguese.

Well! Caught up, for the first time on Brazilian soil. Perhaps it's time for some general observations.

On você, just mentioned: the textbooks lie. Almost everyone says você to me: Lica, his parents, Shirley-- in fact I haven't heard o senhor yet. Lica says things are changing-- he was brought up to say o senhor to elders, but never got used to being called o senhor himself-- he finds it strange. He says tú is used more in the South, and that te is sometimes used here, as in te amo, which I've seen in graffiti. But it's often used wrong: people mix você and te, or used 3rd-person verbs with tú.

Graffiti is more creative here-- more pictures, some quite elaborate. It's common to see romantic declarations-- less so here, however, than in Piracicaba.

Security is a big concern here. Doors are securely locked, you put iron grates on the windows, you lock up your car everywhere. Every bank has armed guards. At Rio airport you're handed a sheet of paper with advice on security, and even here I am advised to be careful with my camera. It's all quite annoying-- I want a camera as a tool for recording impressions, not as a security risk. And everyone says Rio is much worse.

Security is a big concern here. Doors are securely locked, you put iron grates on the windows, you lock up your car everywhere. Every bank has armed guards. At Rio airport you're handed a sheet of paper with advice on security, and even here I am advised to be careful with my camera. It's all quite annoying-- I want a camera as a tool for recording impressions, not as a security risk. And everyone says Rio is much worse.

Inflation is the other big problem here. It averages 25% per month. This leads to various accommodations. Your savings account bears a similar rate of interest. You pay for almost everything-- meals, gas (alcohol)-- with checks, since cash declines so fast in value. Any offer must be dated, or you might give a price in dollars. If something costs 100,000 cruzados, you might offer to pay 150,000 in 3 monthly installments; as they're worth, successively, 50K, 37K, and 28K, you might be better off. Lica just bought a textbook for 11,000 cruzados; a few months ago, a friend paid Cz$ 3,000. It's impossible to be certain if you're making more or less money than before; financial planning is an adventure... it's crazy.

Inflation is the other big problem here. It averages 25% per month. This leads to various accommodations. Your savings account bears a similar rate of interest. You pay for almost everything-- meals, gas (alcohol)-- with checks, since cash declines so fast in value. Any offer must be dated, or you might give a price in dollars. If something costs 100,000 cruzados, you might offer to pay 150,000 in 3 monthly installments; as they're worth, successively, 50K, 37K, and 28K, you might be better off. Lica just bought a textbook for 11,000 cruzados; a few months ago, a friend paid Cz$ 3,000. It's impossible to be certain if you're making more or less money than before; financial planning is an adventure... it's crazy.

There's quite a mixture of people-- black, white, brown, Japanese, Italian, German, Portuguese, whatever. Interracial couples are common. But class distinctions are evident. Menial jobs are likely to be held by blacks, for instance, while the students at the university are mostly 'white'-- in fact I saw only one black student. Very few blonds; Lica says there's more down south, where more Germans immigrated.

| |

|