For the first time in this survey, I feel I must offer a warning: Mešaism contains much that is unattractive to a modern Western reader, and indeed to myself. It is extremely anti-egalitarian, indeed racist; and alien even to our darker fantasies, which usually indulge individualism rather than collectivism. But religions are not devised only to please modern Westerners.

For that matter our Western religions once blessed slavery, racism, and sexism as well. It may be that a civilization must experience these vices in order to transcend them; certainly Endajué, which developed out of Mešaism, is one of the most egalitarian belief systems on Almea.

In origin Mešaism was a fusion of the beliefs of the Wede:i, the oldest inhabitants of the Xengi plain and the organizers of the first human states (-1550), and the Ezičimi, the Eastern invaders who conquered them (beginning in -325).

In origin Mešaism was a fusion of the beliefs of the Wede:i, the oldest inhabitants of the Xengi plain and the organizers of the first human states (-1550), and the Ezičimi, the Eastern invaders who conquered them (beginning in -325).

The invaders were militarily superior, but they had no experience or institutions suitable for managing an agricultural civilization, and for ruling a much larger population. Inevitably they co-opted Wede:i institutions-- the governmental bureaucracy, the irrigation system, and the native religion.

Both cultures were polytheist (though the Ezičimi had far fewer gods); identifications between pantheons were found and exploited: the Ezičimi god Meša was identified with the Wede:i god Wila:r, Inbamu with Akru:, and so on.

At first worship was kept separate. Wede:i worship was based in temples and conducted by priests, who were given Ezičimi supervisors and made to preach subservience to the Ezičimi; Ezičimi religion meanwhile was family-based, with rites conducted by the paterfamilias.

The Wede:i were told that their god Wila:r (= Meša) had been defeated by the chief Ezičimi god, Inbamu, and that as a consequence they were collectively slaves of the Ezičimi. A peculiarity of Ezičimi belief, however, was that all children of Ezičimi were full Ezičimi. As the invaders took many Wede:i wives, the end result was that the Ezičimi population grew quickly, and the pure Wede:i population shrank. Within a few centuries it was a minority.

By the time of Axunai (established 890), the religion of the plain was temple-based, in historical continuity with the Wede:i worship-- though influenced through and through by Ezičimi ideas and practices. The chief god was even recognized to be Meša, who had in this way apparently undone his defeat by Inbamu, and given the Wede:i the last laugh.

For the next milennium Mešaism was the state religion of all the Axunaic states. At the popular level new cults and practices were devised, while theologically philosophers increasingly downplayed the gods, and worked out an elaborate cosmology of mythic cycles and planes of being.

About 1800, the Hermit Masters started preaching a new doctrine without gods; this developed into Endajué-- a new religion, though having its roots in the Mešaic philosophical tradition. Within two centuries it had officially replaced Mešaism in the Xengi plain.

The exception was Čeiy, which largely resisted Endajué-- only to fall sway to its offshoot Bezuxao in the 2700s. Mešaism did not disappear, however; it remains as a minority religion to this day.

Pronel, a outlying area which retained its Wede:i cultural heritage, retained the Wede:i gods as well (and under their old names). When Pronel was conquered by the Tžuro, it came under heavy Jippirasti influence, and the Cuolese, the modern descendants of the Proneli, tended more and more to pantheism, seeing the gods as aspects of the universal divine consciousness.

Ancient Jeor was also faithful to the Wede:i gods; but after the rise of Axunai the province of Jeor, though independent as often as not, increasingly functioned as an Axunemi state, and its religion became a minor offshoot of Mešaism, and like it was swept away by Endajué.

To simplify things, I will normally cite names and terms in classical Axunašin. In earlier sections it will be convenient to offer corresponding Wede:i terms, in later sections, Xurnáš. The final sections, on the offshoots of Mešaism still practised in Čeiy and Cuoli, will use Teôši and Cuolese respectively.

Axunašin is the language of Axunai, the empire established in 890; the people are Axunemi, singular Axunez. All these terms derive from Axun, the early name of the Xengi river, Wede:i Akśim, which consists of an honorific ak plus śim 'long'.

The predecessor state of Axunai is Axuna, largely consisting of the Xengi delta; during this period Axunemi refers properly only to the people of Axuna, and I refer to the Easterner ethnic group they belonged to by their self-designation, Ezičimi 'the Powerful', singular Ezičiz. (This derives from proto-Eastern *asītses 'great', which also underlies the earliest Cuêzi autonym Zîtēi Enalādi 'great riders'.)

Axunašin is really one of half a dozen Axunaic languages spoken by the Ezičimi, though as the language of the most populous Ezičimi state and its eventual empire it is the most important. I will here ignore its considerable historical and geographical variation; for more on these see the Axunašin grammar.

The later empire gets a new name, Xurno; its language is Xurnáš. The people call themselves Xurney, which I anglicize as Xurnese. (Xurno is not cognate to Axunai; it means '(country) of the dawn'.)

The religion itself had no recognized name in Axunašin, though a distinction could be made between kapudo goreš 'temple worship', the priestly worship of the people, and kapudo komei 'home worship', the rites celebrated by the Ezičimi father at his hearth. In the days of Axunai it was useful to distinguish dusočuvakudo 'orthodoxy' from zočurudo 'heresy', but these were divisions within Mešaism.

In later times it became necessary to distinguish Mešaism from Endajué and other religions, leading to the Xurnáš term Mešaxao.

All the cultures of the Xengi plain used calendars dating from the establishment of their own states; when the plain was divided (as it usually was), this resulted in a bewildering variety of reckonings. The most important of these are Axunemi reckoning (from Z.E. 890), Xurnese (from 2530), and Čeiyu (from 1741).

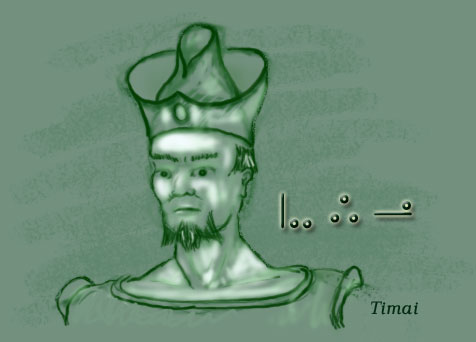

The Wede:i year began with the spring planting; the Ezičimi year began in early fall. Timai, the founder of Axunai, not only renumbered the year but moved its start to the date of his proclamation, which happened to be in early summer. The Xurnese did not change this.

Here's a handy reference chart of the epochs we'll be talking about:

from -1550 Wede:i period -325 Ezičimi period 100 Age of Many Kings 890 Age of a Thousand Suns (height of Axunai) 1300 Age of Decline 1682 Age of Petty Kings 2530 Age of Xurno 3017 Revaudo Revolution

The major gods are these:

Wede:i Axunašin Xurnáš totem gen element landmark Wila:r Meša Meša hawk m air planet Išira Tokna:n Evonanu Evan carp n water lake Van Akru: Inbamu Imbamu lion m fire the sun Raśakma Welezi Elis fox m diamond planet Vereon Aklu:ma Xivazi Xiaz whale f water the ocean Maun Moun Mun leopard m wood the forests Losuna:n Jenweliz Jeywelis elk f emerald planet Hírumor Yaujina:n Meidimexi Midzim beetle f earth planet Vlerëi Jaukaroda Ušimex Aušimex wolf m gold planet Caiem Songkana:n Emouriz Emuris bear m jade planet Imiri Begong Nejimex Nejimex eagle m silver moon Iliažë Birbi: Nejimexi Nejimec owl f iron moon Iliacáš Śabukma Nejimez Nejimes swallow n mercury moon Naunai Akśim Axun Asu snake f water the Xengi

As the table suggests, the essential characteristic of a god was not his portfolio ("war", "unmarried girls") but an animal symbol or totem. Artistic portrayals of the gods incorporated features of the totem-- generally the animal's head and body covering on a human form, though sometimes only the face was animal. Like the Egyptians or Hindus, the Ezičimi seemed to prefer inhuman-looking gods. The gods also had the power to disguise themselves as fully human, or as fully animal.

As the table suggests, the essential characteristic of a god was not his portfolio ("war", "unmarried girls") but an animal symbol or totem. Artistic portrayals of the gods incorporated features of the totem-- generally the animal's head and body covering on a human form, though sometimes only the face was animal. Like the Egyptians or Hindus, the Ezičimi seemed to prefer inhuman-looking gods. The gods also had the power to disguise themselves as fully human, or as fully animal.

The animal nature of a god had several consequences:

The gods are not creators, but denizens of the universe like ourselves, only more powerful. It is their task to rule the world. Mešaic prayers are full of praise, but the praises are almost always flattery masking supplication: the relationship of man to god is very much like the relationship between a man and his (corrupt, egotistical, and very human) ruler. (In neither case did the worshippers complain of the arrangement. Those in authority were expected to be venal and aloof. Rulers and gods wanted to be respected, not loved.)

Cities and states had patron gods; the state would maintain temples and priests to intercede with them constantly, and to hold public rites and festivals. The god of the most important preconquest Wede:i state, Yenine, was Wila:r; the Ezičimi idea that Wila:r was the god of all the Wede:i probably derives from this.

Some of the chief Ezičimi/Axunašin cities and their patron gods are listed below. (Gender and totem are listed for local gods not found in the previous table.)

The Ezičimi relied partly on personality and partly on astronomy to make identifications.

Wede:i Axunašin Region God gen/totem -- Weinex Xengi delta Meša Weteak Wetak Xengi delta Xivazi Yenine Yenine Xengi delta Meša La:iral Leiral Xengi delta Nejimez Bi:dau Bidau Xengi delta Axun Losuji Losuji middle Xengi Jenweliz No:gala:i Nogalei middle Xengi Nejimex Tura:l Tural middle Xengi Nejimexi Śinji Šinji middle Xengi Inbamu Tanngaza Tannaza upper Xengi Ušimex Raśakbori Rašakbori upper Xengi Welezi Na:iral Neiral Moun Moun Yewor Yewor Pronel Bukanan f / deer Yeśela Yešela Doju Jeitun m / coyote -- Tannevi Tanel Welaviji f / bee Songkana:n Sonkan Gotanel Emouriz Tokna:ndau Evonanu Lake Van Evonanu Saiśi Sayiši lake Van Akkin n / frog -- Mešadi Bolon Meša -- Jenevi Bozan Inbamu Yaujina:n Yaujinan Niormen Meidimexi Jeinizun Jeinizun Niormen Sukwenka m / swordfish Na:iwor Naiyor Niormen Nejimex Mo:mor Momor Jeor Rukneiji n / crab Do:nai Diwelezi Jeor Welezi Wa:ior Weior Čiqay river Ušiwaruz m / golden eagle

There were very many minor gods, many of them identified with wild animals (domestic animals had no gods) or with places; there were also divine officials (depicted either as humans, or in the same shape as the god they served, but smaller), promoted ancestors, and monsters.

The result of two gods copulating was generally a chimera (nanudič) with aspects of both gods' totems-- e.g. the son of Inbamu and Nejimexi, the war god Jugimex, was a mixture of lion and owl. These mixtures proved extremely popular, inasmuch as worshipping them addressed both parents as well and drew on their power. Ultimately mixtures of all the major gods were devised-- irrespective of sex; Šagis, the hawk-wolf son of Meša and Ušimex was a favorite; his inheritance of vision, speed, and ferocity made him a tracker, and the god to approach to find lost items.

Asked to define the gods in one word, a philosopher offered zetuvači-- unlimited, without restriction. A god, in other words, does not suffer the limitations of a human being, whether physical, social, or moral. In stories the gods often act like creatures of pure id-- creating and destroying with abandon, ravishing mortals who take their fancy, intervening in human lives on pure whim. This was, again, not far from how the Wede:i and Ezičimi saw their kings. And like kings, the gods seem to live in splendid isolation: no gods are married to each other, and only the chimerae have parents. Their closest bonds are with their worshippers.

After the rise of Axunai, rulers were not all equals; the emperor in Inex had a theoretical claim to be sovereign over the entire Axunaic sphere. Reflecting this, Meša (by now no longer associated with the Wede:i, and no longer subservient to Inbamu) was seen as lord of the other gods.

(This was a sort of double usurpation. Meša was the traditional god of Yenine, a short distance downstream from Weinex, whose traditional patron was a colorless local god named Welsakana ('Old Fish'). The patron god of Axuna was (no surprise) Axun, of obvious importance to the riverdwellers and the patron of the original capital, Bidau. When Weinex became the capital it ditched the Old Fish, who had no appeal elsewhere, in favor of Meša-- going so far as to appropriate Yenine's largest and holiest statue of the god.)

Except as noted, the description below applies to classical Axunemi belief.

The Wede:i word for the world was komoma, the Big House (Ax. komeï). They pictured the Xengi plain in the form of a house, with the mountains to the west, north, and east and the sea to the south as its walls. Actual houses were built in imitation of this divine architecture, with the door to the south and the hearth on the north side, representing the sun, which was always in the northern half of the sky. Cities also were built with their main entrance to the south.

It was believed that both gods and animals lived either belowground (or underwater), or in the sky-- only humans and domestic animals lived on top of the ground in houses. The placement of domestic idols reflected this: they were either installed in the ground under the house, or in the roof above people's heads. The placement of altars and holy places in temples followed the same principle: to reach the gods you must either climb or delve.

In addition, there were bodily substances (kimini) associated with each of the nine combinations of these:

body spirit contrasting qualities source of water - mii the female - zimun youth harvest love, hatred earth - suz the male - gumun night planting creativity, destruction wood - gule the light - silirti age day wisdom, honor

An elaborate medicine and psychology was elaborated from this basis, proceeding from the idea that disorders were caused by an overabundance or a weakness of one of these nine combinations.

female male light waters blood semen urine earths liver, brain, etc. muscle heart woods ovaries testicles bone

The creation of new life, via intercourse or agriculture, was seen as a male activity; the bearing and nurturing of life (thus, birth and the harvest) were female.

The Mešaic mind, which never shied away from declarations of value, considered the female principle lowest and the light highest; but none of these principles was good or evil-- indeed, Mešaism rarely makes judgments of this sort about anything. It is interested in the right thing to do, of course; but it almost never reifies evil in the way of terrestrial monotheisms: there are no demons per se, no enemies of the gods, no men or nations declared evil.

The ktuvoks might have provided a model for evil, but there was little contact with them till the 1600s. Perhaps this was one reason the governor of Moun was open to ktuvok promises. After this debacle, and the general bad times following the fall of Axunai, there was more of a sense that there were definitely malicious spirits out there.

To the Ezičimi and Axunemi (but not to the Wede:i) there were three sexes. A person of the third sex was an ewez, literally a 'middle person'. It would be sensible for the ewemi to correspond to the third spiritual principle, the light-- but generally the opposite tack was taken; they were considered less than male and female. Some philosophers explained that the light was transcendent, beyond male and female, while the ewemi were insufficent, and did not attain either.

If the Ezičimi rule Axunai, it is because the present cycle (šarus) belongs to them; the previous cycle belonged to the Wede:i. Before that was a cycle of elcari; before that, two cycles of ilii; before that, a cycle of men called Čerengi, and so on. Many of the legends and myths of Axunai are set in the Čerengri period, which was one of nobility and mighty deeds. However, there is no tendency in history toward progress or decline; there have also been cycles of great degradation and misery.

(The plural of šarus is šaruvi; X. šarc, šarp. Both Axunašin and Xurnáš plurals are a bit difficult, but don't lend themselves to anglicization... šaruses?)

The cycles can be strikingly different from one another. Not only men and ilii, but stranger beings may dominate a cycle: there have been cycles of birds and of talking cats. However, as the cycles are endless, the people or race which dominate one cycle will eventually dominate another. (The ancient Mešaic philosophers anticipated the observation of Poincaré, stating that an exact recurrence of any one šarus, as well as any number of inexact repetitions, were inevitable.)

This feeling contributed to the continental crisis of the 1600s, when the ktuvoks attempted to subvert all the major civilizations of eastern Ereláe, and ended up being conquered by the combined forces of Ervëa and Attafei. The attempt by Neirimi of Moun to conquer Axunai was partly inspired by the idea that a sufficiently bold leader could begin the revi šarus.

The empire of Axunai was ended in a palace coup in 1682, ushering in the Age of Petty Kings and confirming for many the idea that the šarus had ended or was ending. The Hermit Masters of Endajué played to these ideas, and indeed in Endajué the rise of the new religion is accepted as the beginning of the revi šarus.

However, the Čeiyu Mešaists, noting that the empire was later reconstituted, hold that the Axunaic cycle did not end until 2483, when the entire plain was occupied by the Gelyet-- thus passing the torch of Mešaism to Čeiy.

Revišaruvudo ('milennialism') has never entirely died down, and may have paved the way also for Revaudo. We will return to this in the chapter on Endajué.

(This is a considerable elaboration on the Wede:i system, which began with one additional mura, that of the dead-- thus Murineli 'the land of the dead'. Later on it was decided that our spirits enter this mura from a less-formed one below; and by the time of the invasion philosophers were playing with as many as half a dozen muran.)

The beings who inhabit lower mureši can affect this one, in the form of diseases, curses, and possession (an evil man is one afflicted by a spirit from a mureč or two down). The inhabitants of the higher mureši (that is, the dead, as well as other powers native to the next mureč) can also affect us, generally benevolently. The dead do not expect to be remembered or propitiated; rather, they are interested in their descendents' fate, or they simply wish to amuse themselves with a simpler world.

The doctrine of the planes was increasingly elaborated; it offered more explanatory power than the gods themselves, and paths of spiritual development as well. Dreams and visions were interpreted as glimpses of other mureši, below or above us-- always true glimpses, in fact, though other mureši were so alien that they still required expert interpretation.

Philosophers usually insisted that the mureši were separate worlds or dimensions and were only traversed at birth and death. This sort of thing is not easy to get into people's heads; as we see from the Divine Comedy or The Journey to the West or that disaster Star Trek V, people prefer to think that one can reach the home of the gods by a physical journey, though an arduous one. Mešaic mythology is full of obscure links between mureši, and not a few sages claimed to have toured the nearby planes.

One could not permanently move to another mureč before death, but one could seek to remove influences of lower mureši and pre-adapt to those to come; great sages spoke of šuvokunudo 'risenness', living mentally in the next mureč.

Some suggested that there were gaps in the planes-- in effect the universe was something like a Photoshop document, made of layers cut away in spots so you can see those below. The usual idea was that the sun and planets, which seemed not to follow earthly laws and were never corrupted or replaced, were several mureši above our own; the stars, which do not even move, were even higher.

Their relationship to the planes is more obscure. To the extent that they asked the question, the Wede:i considered the gods to belong to our plane or to all planes. As the planes multiplied the latter option seemed increasingly untenable to the Mešaic worldview, which shied away from all generalities and absolutes.

The most common view was that the gods were entities from three or four mureši above our own, pinned down as the mureč naniei, the plane of the gods. As this is not far above us in the chain of being, the way was open to speculate about even more advanced and powerful beings beyond; some of these even inspired popular cults, especially Xuris, a talkative entity and vouchsafer of visions from ten mureši up. Some Mešaic sages even suggested that Jippir, the obviously potent deity of the Tžuro, was simply a god from the level above the mureč naniei.

By the Age of Petty Kings the anarchy of life on earth was countered by a proliferation of omnipowerful beings on many levels-- new cliques of them were always being discovered, much as in the Marvel Universe. Even better than getting one of these on your side was becoming one; manuals were written to advise on the fastest possible rise from human to ancestor to god to beyond.

The difference in mental attitude from Caďinas has been profound. The central fact of existence has always been the state. It may be corrupt and its rulers ripe for replacement, but it is always essential. In the north one could always in theory pull up stakes and move to a new area outside the state's control. In the south, there was no such option; the habitable area was the area under the control of the state or one much like it.

(There are marginal areas unsuitable for irrigation-- Jeor, Pronel, Čeiy, and the plains to the northwest-- and historically these have either been independent, or a thorn in the central government's side.)

The southern religions have always preached support for the state, the importance of the collective good, and the social lubrication necessary to a populous and busy state: manners and decorum; respect for superiors; fair and just treatment for inferiors.

Wede:i society was divided into five classes:

Conspicuously lacking is a class of merchants. These societies had no markets and no merchants; any economic enterprise above the level of the individual farm or workshop was managed by the state.

War was the province of the nobility, who not only commanded the army but made up the bulk of the soldiery. (A peasant levy could be raised in an emergency, mostly for defense.) As a consequence, armies were fairly small-- which would have serious consequences when the Ezičimi invaded-- though at the same time the nobility was fairly large, perhaps a tenth of the population.

Nanungitera's legal code, the Guśali Sa:unak (Canons of Respect, -610), sets out the responsibilities of the social classes with admirable firmness and brevity. So long as one fulfilled the obligations of one's rank, there was no real possibility of acting with greed, arrogance, or excess. Brutality toward the lower orders, however, was a serious sin-- though the law almost always allowed repentance to take a monetary form. (Rape and adultery, for instance, were punished by requiring the offender to pay the woman's bride-price.)

Ironically, or inevitably, the southern religions have always provided means of escape from the demands of society. The Canons, for instance, ordained one day a year (benśentin) when all laws were reversed, and blasphemy and insubordination reigned. Culture heroes are often rebels and those (like the gods) who can do as they please without limits. Spiritual enlightenment has often involved almost narcissistic levels of self-absorption.

Inevitably they found themselves adopting the traditions and institutions of the conquered. The bureaucracy, the irrigation works, and the religious hierarchy were given Ezičimi leaders, but otherwise left alone. Peculiarities of the Wede:i system were retained, such as a dual hierarchy of control ('fiscal' and 'ethical').

The Wede:i nobility was decimated by the war, the survivors either demoted or fleeing to the free Wede:i states in Jeor or Pronel; in effect it was simply replaced as a class by the Ezičimi. There was not even much numerical effect: the Ezičimi were more numerous than the Wede:i nobility by about 50%, a factor that contributed to their military advantage, but still scant in comparison to the rest of the population.

Nonetheless the invasion was more than a replacement of the nobility; the Ezičimi were a different culture, at least initially spoke a different language and worshipped differently from their subjects, whom they considered unmanly and servile.

The end result was a form of theologized racism: it was taught that the Ezičimi were superior beings--fiercer, hardier, more worthy of respect, and requiring a greater level of material comfort. A Wede:i was to obey an Ezičiz of any station without question; this was the judgment not only of the authorities but of the gods.

In other similar situations, conquerors may be absorbed into the population (e.g. the Manchu among the Chinese), or simply ousted (as with the earlier conquerors of China, the Mongols); but a quirk of Ezičimi custom led to a different outcome. Well-off Ezičimi were allowed to take multiple wives, and as conquerors they took full advantage of their privileges: the Ezičimi lords often had five or more wives, most of them Wede:i.

(The lords also took native concubines [neruweno wedewi 'bed slaves'], but the children of these temporary unions were not considered Ezičimi. The woman was put away before a year ran out; otherwise she had grounds to assert her status as a wife.)

The resulting children were themselves deemed to be full Ezičimi, to be brought up learning Ezičimi customs, speaking the Axunašin language, and entitled to the respect due to the master race.

Early records suggest that this was not uniformly the case in the first or second generation after conquest. However, rulers preferred being able to choose their successors from the entire pool of their offspring, and indeed favored the sons of Wede:i women, since the mothers' families could make no demands on them. As well, the Ezičimi believed that the generation of a child or any living thing was entirely due to the father's seed; the mother's role was to bear the child.)

The initial result was a great increase in the number of Ezičimi; the long-term result was the watering-down and eventual abandonment of the aristocratic principle. Like a pyramid scheme, the system was bound to break down as the total wealth--relatively fixed in such a technologically stagnant society-- was spread out among more and more people. Within half a milennium almost the entire population could claim Ezičimi blood. The earlier aristocratic doctrines were no longer the defining characteristic of the society, but only a set of rules for dealing with the untouchable servant class of full-blooded Wede:i which persisted for some time.

This does not mean, of course, that the Wede:i died out. The Ezičimi 'naturalization rule' ensured a steady increase in the number of 'Ezičimi', but the proportion of original Ezičimi genetic stock was unchanged. Ezičimi, of course, only had Ezičimi children. Large numbers of Wede:i women married Ezičimi and thus had Ezičimi children. The rest married Wede:i men; but their daughters might also marry Ezičimi. As in most aristocracies, the land passed exclusively to the eldest son. Other sons were however entitled to some share of the family's wealth, and this, along with the distribution of dowries, spread wealth out from the aristocracy. Naturally, within a few centuries there were families of extremely poor Ezičimi.

The simplest mathematical model that is closest to the known facts is that the increase in percentage of Ezičimi was arithmetical rather than geometric: about 13.3% per century. The best explanation is that the wealthiest Ezičimi were picky, and the rest were poor. That is, those who could afford Wede:i wives preferred the 'best' ones, from good families, and there were simply fewer and fewer of these. Slightly less well-off Ezičimi were less picky, but still avoided those at the bottom of the ladder. The poor Ezičimi could not afford any but very poor Wede:i. The net result was that though the percentage of Ezičimi kept growing, the percentage that found Wede:i wives kept dropping, finally stabilizing after about 600 years with an undesirable slave underclass comprising 10% of the population.)

Racist societies can persist for centuries, as the history of Peru or Mexico shows; but the Spanish did not count children of their Indian brides as of their own race. (Arabs did-- which is why the lands conquered by Arabs are now almost all Arab.) One might expect that the Ezičimi would sooner or later disdain to take wives from the servant class; but their very racism ensured that they would do so eagerly as long as that class existed: it was a matter of prestige to have several Wede:i wives, and multiple wives could only be acquired from inferior classes, not from among one's peers.

European feudalism emphasized the commonality of fiefdom: everyone, serf and lord, held some fief, which accorded rights and responsibilities both toward one's lessers and betters. Ezičimi society made no such connections, and responsibilities were almost entirely downward, mitigated only by a disapproval of overt cruelty.

In no Ereláean realm outside Munkhâsh was power more nakedly paraded. The minor occupations, such as peasants, bakers, masons, craftsmen, and household slaves, existed only for the services they provided to the powerful. All occupations were hereditary, and migration between cities or pešenkei was not allowed. Only a few at the top of skilled professions-- artists, architects, military engineers-- could shop around for the best lord.

The nive (king) was at first simply the boldest and hardiest of the Ezičimi geivemi, chosen from among themselves in order to further prospects for booty and conquest. In the course of the conquest his position improved from warlord to emperor, the symbol of Meša on earth, the arbiter over all Ezičimi, and the source of estates: often in practice and always in theory he granted the nobles their estates, and he could revoke his gifts.

Ever conscious of their precarious hold over a populous nation, the Ezičimi never forgot the necessity for military order, and although disputes between lords were common, one did not talk back to the nive.

As the conquest was consolidated, the nive's position became more difficult:

During this time the racial basis of the Ezičimi aristocracy slowly declined, not out of greater tolerance, but because more and more of the population was 'Ezičimi'. They could not all be nobles; at first excess children and forgotten branches of the family were shunted into the half-respectable priesthood and bureaucracy, but eventually there were Ezičimi peasants, many of them only marginally better off than the remaining full-blooded Wede:i.

A pešenke was still governed by a geivez (lord), with a substantial caste of nobles whose main task was to serve as cavalry in the wars. There was now, however, a gradation of lesser positions-- lesser lords with sub-estates (once granted to favored sons or distinguished warriors, now semi-autonomous fiefs); garrisons of infantry (the troops were commoners, the officers nobles; compare the all-noble cavalry); landowners distinguished from the wealthier peasants only by their genealogical connection to the lord.

The nobles still felt that priesthood and statecraft were matters undeserving of attention. Indeed, a landowner generally did not bother to learn to read; his only intellectual avocation was likely to be genealogy, as lines of descent, loyalty, and inheritance continued to be important determinants of his prospects. But the intellectual pursuits were quickly 'Ezičimized', and to be Ezičimi was no longer identified solely with military prowess.

The nivešumi were each small hydraulic states; the king thus differed from the nobles not just in degree but in kind. He presided over the government bureaucracy, the courts, tax collection, and the waterworks, as well as the more important priestly orders.

Nobles, as members of the plundering classes, were exempt from taxes. In theory the nive's officials collected taxes directly and gave half to the local lord and half to the king. In practice both the officials and the nobles did their best to increase their share of the take; nobles might also assess taxes of their own. A weak nive was lucky to receive anything beyond the revenues from his personal estates.)

A strong nive enforced unity and order among his nobles; but a weak nive was little more than the chief of a rowdy gang of warlords, and could be supplanted by one of them-- or by a more organized neighbor taking advantage of the chaos. (Occasionally the lords would have wars of their own, though a strong nive would prevent this.) The wars provided one of the few upward paths in society, as conquered estates were often awarded to outstanding generals. (Losing lords of course retained their Ezičimi status, and might even remain as important landowners.)

The Jeori invasion, and the subsequent conquest of the Xengi plain under Timai (890), changed the political situation dramatically. Henceforth there were not a multitude of kings but one Emperor (niveï), chief light of the Age of a Thousand Suns (Mu ezer torewi soumax).

The Jeori invasion, and the subsequent conquest of the Xengi plain under Timai (890), changed the political situation dramatically. Henceforth there were not a multitude of kings but one Emperor (niveï), chief light of the Age of a Thousand Suns (Mu ezer torewi soumax).

The feuds and battles of the lords became a thing of the past; the entire empire-- a realm the size of Charlemagne's or Justinian's-- was run, with dispatch and efficiency, from the niveï's capital of Weinex (modern Inex). The nobles were no longer warlords with substantial power over their own domains, and with a shot at becoming king; they were simply large landowners, as much a subject to the Emperor as the least peasant or slave, though of course in a much more comfortable position.

The administration was divided into seven Adjutances (Kurtudawi):

In earlier times the nobility were in essence a standing army, each geivez providing a portion of the total force. The emperors made the army independent of the geivemi; both horse and foot soldiers were now equipped and paid by the emperor. The nobles still provided the officers, but they were no longer required to supply an armed force of their own-- and no longer had one for making war on their own.

The nobles also found themselves on smaller estates, as sub-estates were separated off to become full (though smaller) wituvei in their own right, and divested of their former private armies.

Taxes were assessed on landowners-- nobles were no longer exempt. (At least at first. Later emperors, forgetting that favors bestowed on the illustrious are taken as no more than their due by his descendants, started granting exemptions again; the eventual toll on the imperial revenues was significant.)

Where in the old system, as noble and tax collector squeezed, the nive was always the loser, in the new system the Emperor always received his due. In the early days, rates were low enough that the landowner could pay his assessment out of levies on his peasants, and retain a healthy surplus for himself. A few years of famine, or an overspent inheritance, could leave a landowner in dire straits, especially as rates were determined in the early days of the empire and took no account of changes in land fertility, settlement, or the irrigation structure. A landowner in reduced circumstances had little recourse but to sell land, and many an estate dwindled into nothing. Things only got worse in later centuries, as constant war impelled the nivewi to increase the rates.

An Axunemi estate consisted of a (male) lord (geivez) and his wives; a large assortment of relatives; and the local servants, artists, craftsmen, peasants, and other laborers. An estate could range from several square kilometers to the size of a county. A landowning family generally had its own temple, with one or more priests.

The cloud of relatives posed a delicate problem: A large cloud of satellites was prestigious and admirable; but there were limits. Past a certain point remote relatives must pass from privileged drones to workers. However, it was unseemly for this impoverishing process to occur in plain view. To save face, the remote cousins would discreetly move off into city life, or into the imperial service, or the army, or onto other estates.

The peasants themselves generally represented a late form of this same process. In earlier times, remote branches of the family simply set up farming households within the estate-- it was useful, and one had to do something while waiting for the next war-- and these households, multiplying with multiple Wede:i wives, and dividing their inheritance, ultimately became little more than tenant farmers.

Arguably the lot of the peasants (meidemi) improved under the Empire-- though it was still no picnic. Legally they owed only taxes (in cash or in kind) to the landowner. He could not evict them from the estate. The peasant could even lodge a complaint against his landowner in court. The odds were against him, of course, not so much because justice was corrupt, but because the landowners knew court procedure and the peasants didn't. And it was possible to cruelly mistreat peasants without violating any laws.

More significant was the general prosperity of the Imperial years. The Plain was no longer wracked by civil war; the irrigation works were improved and maintained much more seriously; new tools and techniques improved productivity. The peasant in the Age of a Thousand Suns had more than enough to eat, was generally left in peace so long as he paid his taxes and behaved himself, and had some opportunities to better himself.

Under the empire, Mešaism increasingly preached mercy and deplored brutality. Masters were exhorted to treat slaves and peasants kindly, make sure they had enough to eat, and not to split up couples. Cynically, we may note that power-sharing systems tend to break down when empires become too large, and that mercy is a cheap way to reduce social frictions that otherwise may lead to revolution. Nonetheless, the softening of mores was a welcome change for the lower orders.

Although the pure Wede:i class disappeared, and with it the racial basis for the class system, there always remained a bottom or slave caste-- still called wedeï, which simply became the word for 'slave' (edi) in Xurnáš. New conquests provided a steady supply of slaves; certain crimes, such as rebellion, blasphemy, murder of a noble, or mother-son incest, could result in demotion to slave status; and wars or natural disasters could displace whole populations of peasants who, having nowhere to go, drifted into more or less the same position.

(Technically they were poukuvei, 'the fallen', and were not bought by their eventual masters, but taken in out of a laudable mercy. While slaves were considered only semi-human, the poukuvei were merely cursed by fate-- though probably for cause. The difference in treatment was negligible.)

Under the Empire, slaves belonged to the landowners, not to the Ezičimi class as a whole (that is, the non-slave population). Peasants and servants thus no longer had the right to take slaves as brides, while their betters now chose not to. (Slaves could still be concubines, and there was no longer a time limit on how long.) Slaves were always a minority in Axunai, and were generally considered more trouble than they were worth: lazy, brutish, foreign. There was no emphasis, then, on breeding more slaves. Slaves did not have many children (ones that lived, anyway); if those they had didn't speak Axunašin, or if the parents had committed particularly heinous crimes, the children remained slaves. Otherwise the children could be adopted as servants or wives, and thus work up one rung of society.

The empire had a substantial middle class, however, and this tended to grow over time. Its chief component was the imperial administration: engineers, judges, bureaucrats, military officials, priests, and innkeepers (important members of a system which depended on frequent travel).

The new tax system also created a new class of small landowners. Landowners in need of cash might sell parcels of land to a peasant family; the peasants, paying the same land tax but living a much more modest lifestyle, often greatly prospered, and increased the size of their holdings over the centuries, perhaps ending up as a respected landowning family in their own right (and thereafter declining in their turn). If a landowner was convicted of serious crimes, his estate could be divided into smaller estates. Finally, when new regions were conquered by the Empire (Jeor, Bolon, Pronel, Čeiy), land was often offered to peasants to encourage settlement.

(This last factor was most important in Čeiy, which ended up with a very large class of free peasants. That, and its dependence on rainfall rather than irrigation agriculture, was to be of enormous moment in Čeiyu history.)

In addition, the number of people unattached to any estate was large and growing. Artists, independent priests, mathematicians, and philosophers formed an increasingly substantial intellectual class, whose most successful members could dispense with aristocratic patronage. Foreigners also lived in the cities, engaged in trade, mining, metalworking, or other un-Axunemi pursuits. There was a small but growing class of independent craftsmen. There was also an underground-- thieves, assassins, suppliers of vice.

By modern standards the system was inefficient and stifled innovation; but it was sufficient to support a large warrior and bureaucratic class, and its neighbors were impressed with its scale of operations and with the general prosperity of the Empire. The individual Skourene was more prosperous than the average Axunez, but Axunai was so much larger (and more well ordered) than any Skourene state that this fact, even if noticed, would not have been taken as cause for reflection.

(To be precise, the festivals in the temple patronized by the local lord were mandatory, as well as a certain number of those at other temples. In most areas it worked out to about one every fifteen days.)

For the peasantry, festivals were almost the only chance to eat beef. A peasant might have a cow to supply traction, dung (used for fuel and as a building material), and milk; it was too valuable to eat.

As an old saying warns: Tek nanudeč nanu dačei, without a sacrifice, the god gives nothing. One never came to the temple empty-handed, and indeed the chief support of the priests was the grain brought by the peasants to the festivals.

The temples offered a further service: sex. The monzui ranuri 'girls of the interior' were slaves given as offerings to the gods; sex with them was the reward for winners of the games, for peasants who brought an unusual amount of grain, and others the gods wished to reward. Their time was not for sale, but an enterprising person could find ways of making himself useful to the temple and winning this reward. There were ewemi who fulfilled the same role.

There were also itinerant priests-- tek goro jeimi, 'priests without a temple', normally because they served gods obscure enough that no one had seen fit to build a temple for them. Though they aroused general annoyance by begging for alms, they were also closer to the people-- they offered blessings or cures for a much more modest offering than the temple priests.

A temple was normally dedicated to a single god, though it would also have niches and rites for associated gods-- partly because one never went wrong bowing to a god, partly to provide a divine court for the temple's god. There were a number of multiple dedications, usually to trinities-- e.g. to the three moons, or to one of the chimera gods and his or her parents.

A temple generally contained a large, ancient statue of the god which in the mythical imagination was the god; it was moved to the main worship chamber during the day and to an inner compartment at night, redressed and redecorated at intervals, and grouped with icons representing its court, all of this being accompanied by rituals spoken and enacted. Sacking a city, the victor might destroy or desecrate idols; this was a demoralizing blow, though it was always possible to rehouse the god in a new statue.

Temples came in all sizes; but the largest ones in each cities were huge establishments with hundreds of priests and an even larger allotment of servants and peasants. The temple of a state's patron god was usually attached to the palace and organizationally intertwined with the royal household. The height of this was the Temple of Meša in imperial Weinex, which covered 15 hectares and employed 1200 priests.

If anything was responsible for eroding this custom, it was the practice of taking Wede:i wives, who co-operated with the Ezičimi rites but insisted on continuing temple worship, and of course took their children along. Many lords found it convenient to add a priest or two to the household. They were cheap retainers and good liaisons with the people, and could write.

The priests were deferential, used the Ezičimi names of gods, and were adept at picking up Ezičimi stories and traditions. Thus there was no sense of alienation or usurpation as the priest gradually became the center point of the household's religious life.

By the classical period, little remained of the former traditions but certain formulas intoned by the paterfamilias during this or that rite-- words he learned from the family priest.

Being a family priest (doumiš jeim) was a hereditary position, and the priest answered only to the family, not to the temple, so that in a sense each family had its own personal religion. On the other hand, they were the opposite of innovative, and used the same scriptures as their colleagues, so that there was no serious drift from the temple religion.

Until quite late, no one simply founded an order. The founder would be a heretic, a hermit-- an orjibirti, a word which, significantly, means 'hermit', 'exile', and 'suicide'. To leave the collective was an almost insane descent into loneliness, starvation, and madness; but it was sometimes necessary to get a little fresh air into one's brain. Most of the orjibirtui came to nothing, but some achieved the enlightenment they sought, and became sages, gathering followers.

Eventually a noble or king might give them a grant of land (narideč), and this became the monastery. Unlike a European monastery, the monks (naridečemi) did not support themselves; part of the grant included peasants to work the land. The monks were supposed to live simply, but their task was to continue their spiritual journey-- to think, study, pray, have visions, prophesy.

Monasteries might have several purposes:

There was a tradition of secular teaching as well-- generally a group of students gathering round a prominent thinker. (These were often clerics themselves, or graduates of the monastic schools.) These never received official support, and thus tended to die away as the teachers died or lost popularity. The best-known was the Bitikniz, a salon founded in the 1020s by the philosopher Jugiroz in a palace lent by a noble supporter; it was maintained for nearly a century by his followers, and had a great intellectual influence.

(Monks, like peasants, wore coarse hemp cloth rather than linen or cotton.)

Perhaps half of the temples and monasteries allowed female priests and nuns. All were open to the ewemi, the third sex. Almost all allowed marriage; celibacy simply made little sense to the Mešaic mind.

Monasteries and temples were generally built under royal or noble patronage, and the lord retained the right to name the chief priest or abbot-- though some were allowed to suggest a favorite son for the position.

The prototypical celebration was a public festival. The two largest festivals were one at planting, dedicated to Meša, and one at harvest, dedicated to Inbamu; both were preceded by fasts.

There were also rites to welcome astronomical events. If a god was associated with a planet, his temples observed its calendar, as seen from Almea. There were particularly grand festivals at the temple of Meidimexi for the oppositions and conjunctions of Vlerëi.

In the Ezičiz ritual of birth, the jouvišus or bloodletting, the father cut himself and let blood spill on the baby, signifying his acceptance of the child and his willingness to give his blood in the same way as the mother giving birth. (It was actually this ceremony, rather than the conception of the child, that marked the child as an Ezičiz.) Oaths of fealty or friendship were also celebrated with a jouvišus.

Marriage is discussed in more detail below. The key element of its ritual was the two fathers enduring an ordeal together; in earliest times this often consisted of being tied together at the back and resisting a mock assault, signifying that the families were now military allies. If one father was Wede:i the ritual involved building a symbolic house instead. In later times the fight became a dance, still named the dusokueč 'back-fight'.

Rites (the xučideiz) were offered to remember the dead once a year; it was also customary to set aside funds to have special remembrance rites on another day-- the wealthier the decedent, the more xučideimi were endowed. This custom seemed to grow out of control; kings and emperors issued decrees limiting the years of xučideimi allowed (ten for a landowner, twenty for a noble, thirty for a king) and which days could be set aside for them.

In time the New Rites conquered, and were conquered. It was fashionable for Wede:i families of means (while these remained) to imitate their conquerors and celebrate rites in the same way; while the family priests, originally simply palace retainers, became first the custodians of ritual and then the chief celebrants. This process inevitably changed the nature of the rites; they were no longer only acts within the family, but now involved the people and the gods as well. Births, for instance, were welcomed by the entire community, and the blessings of the gods beseeched.

Three of their manuals became part of the classics:

The Axunašin versions are modified to use the Axunašin names of the gods; the compilers also interpolated praises of the Ezičimi and warnings from the gods that the Ezičimi must be unquestioningly obeyed.

(Wede:i) (Axunašin) Na:nśaukli śebarul Dusočuviei šebareč the Book of Rituals Ngegeali śebarul Suvičudeš šebareč the Book of Rising Na:nku:rali śebarul Nanudešiš šebareč the Book of Propitiation

Under the Ezičimi these books actually became more important, because the only way to ensure that these praises and warnings were included was to insist that priests follow the book. Since there was no central authority, however, the editions in each kingdom diverged. These books of ritual of course included only the Old Rites.

A typical passage from the Zauli śebarul shows that the purpose was not strictly informational:

Jenli śebarul Jeniš šebareč the Book of the Forest Zauli śebarul Zuš šebareč the Book of Sand Jalanli śebarul Jalaniei šebareč the Book of Waves

To cause sweat to those suffering from plague, supplicate to the mermaid's hair to one turn, supplicate to the fat of the Lady Beetle in her salmon aspect to two turns, supplicate to the dull moon riven by the sour fruit of the drinker to two turns; this may be imparted as a powder.

This is not a rite (though it purposely sounds like one) but an alchemical recipe. For supplicating to an aspect of a god, read using the substance associated with that aspect; for 'turn' read 'quantity'. This particular formula combines sal ammoniac (a distillation of hair with salt and urine), bole armeniac (a pale red fatty earth-- earths were the preserve of Yaujina:n), and white lead (lead-- the dull moon-- corroded by vinegar). The misdirections and fanciful terminology were intended to baffle outsiders and rivals.

The magical recipes fall into four categories:

The associations could be complicated. For instance, why was white lead used as a truth serum and as an eye ointment? The chain of associations was as follows:

More simply, one could write the glyph for a god's name with one stroke missing; this would nag at the god till he granted your favor.

The greatest of these works eventually became the two chief Mešaic scriptures:

In the next centuries there was an explosion of religious and philosophical literature; the cream of this is recognized as the Seven Classics (Šeisun uliax):

These seven works were considered to tell about all there was to know, and young nobles (as well as aspiring scholars and priests) were expected not only to read them, but to write essays on them and to reproduce important passages from memory.

Orjibirtiš tibelax The Army of the Hermit lessons from spiritual masters Nanukumiš omuvi Thoughts of Nanukuz sayings of a great philosopher Rodiei endei The Ways of Nations statecraft and diplomacy Zalayei duxudo For the Instruction of Generals war tactics Axunaiš sigadu yutei The Hundred Flowers of Axunai poetry Duxuvax Treasury of Lessons moralistic stories

As an outlook on the world, what did Axunemi Mešaism amount to? We might mention these characteristics:

The ewemi were those that didn't fit the fairly rigid sex roles of the Ezičimi bands. It was said (usually by outsiders; Ezičimi explanations tended to the tautological) that these were the unmanly men and the mannish women, and when we learn that many of them were homosexual, we may think we have their number. But the Ezičimi were using their own categories, not ours.

The ewemi were those that didn't fit the fairly rigid sex roles of the Ezičimi bands. It was said (usually by outsiders; Ezičimi explanations tended to the tautological) that these were the unmanly men and the mannish women, and when we learn that many of them were homosexual, we may think we have their number. But the Ezičimi were using their own categories, not ours.

The prototypical Ezičimi man was a warrior, strong and hard; the prototypical woman was a mother and wife, hard-working and nurturing. Men who were not good with weapons, who messed around with herbs or (later) books, were likely to be classified as ewemi. Same story with women who resisted marriage, or preferred books or bows to babies. A fifth or more of the population was considered ewemi. Only a fraction of these were actually gay or lesbian; we could equally call the ewemi 'geeks' or, more nicely, 'intellectuals'.

Those dissatisfied with their jišeigu were as likely to be women as ewemi. There are many stories of people disguising their jišeigu-- indeed, since there were more possibilities, this sort of thing was exploited quite often in popular literature.

Each sex had a different prototypical body image:

What they couldn't be was lords, kings, army officers, or parents. If a lord had only ewimo heirs, his title had to pass to a remoter male relative. As with the similar restrictions on women, there were in practice ways around this. An ewez might be a regent, for instance, and there are stories of exceptional woman and ewemi with glorious military careers.

Sex need not follow the same pattern. Indeed, the most common pattern of what we'd call homosexuality was a man pairing with a (biologically male) ewez. There were similarly women who enjoyed affairs with ewemi.

Literature about ewemi, like ewimo clothing, went out of its way to hide biological sex. Even very explicit passages never hint that an ewez might have a penis or a vagina, only a dulis, a sex organ.

Ewemi were deemed to be infertile, since it was males who were supposed to father children, and motherhood was the province of females. Since biology did not really cooperate with this notion, there were tricky situations. A biologically male-female ewemi couple might practice contraception or even abortion; or the couple might discreetly have the baby and pass it to a female relative to raise.

Similarly, metaphysics recognized three spiritual principles-- masculine, feminine, and light-- but the latter was usually not identified with the ewimo, except by a few very bold (and usually ewimo) thinkers. This is in part because the spiritual principles were derived from Wede:i cosmology, which did not have the concept of ewimo, and in part because the light was considered superior to the masculine and feminine-- a position that clashed with the social inferiority of ewemi. It was sometimes explained that there was subtractive and additive neutrality: one could have feminine or masculine nature, neither (the ewimo), or both (the light).

The original rule was that an Ezičimi male could have multiple wives (plus neruweno wedewi, concubines, which relationships however must be short term), while Wede:i could not. Many Wede:i men could never marry, because so many Wede:i women were taken as brides by Ezičimi.

The Wede:i may have adapted to this predicament by informal polyandry. It was said that Wede:i men allowed their unmarried younger brothers to sleep with their wives. It's possible, however, that our reports are simply typical upper-class titillation over the supposed open mores of the lusty servant class.)

Ezičimi society was geared to producing warriors-- males. In early days this directive was so strong that the life expectancy of Ezičimi girls, even considering the near-constant warfare, was much less than that of boys: the girls succumbed to sickness, or neglect, or even infanticide. The practice of dowry (ewudou) for Ezičimi girls must also date to this time; dowry expresses a class's estimation that supporting a woman is a burden requiring compensation, and also helps to discourage the upper class from raising daughters. The encouragement of infertile ewemi marriages is a part of the same mindset.

Wede:i girls, by contrast, were valuable: they were hard workers, prestigious for the husband, and produced heirs without creating entangling alliances. The custom was therefore to pay a bride-price (datadou) to the parents of Wede:i girls.

While Wede:i girls were in strong supply, the situation of Ezičimi women was fairly miserable. They were subject to the absolute authority of fathers and husbands; and they represented a financial loss to their families-- their greatest consolation was their right as Ezičimi to boss around Wede:i, especially their husband's Wede:i wives.

There are hints that before the invasion, the position of Ezičimi women was less restrictive. Easterner bands were highly mobile; women were riders too, and taught the use of weapons. Still, the culture valued military glory above all else, and women were deemed incapable of contributing to this.

Marriage to either Ezičimi or Wede:i women created (or reinforced) a bond between the families. It was shameful, for instance, to allow one's Wede:i father-in-law to fall into destitution, while marriage bonds within Ezičimi families strengthened alliances and repaid favors.

If a society isn't egalitarian in modern ways, we should nonetheless not assume that it is the opposite of everything modern; neither rhetorical dystopias nor fantasies of self-indulgence à la Gor are useful models. Ezičimi women were not slaves, and indeed had authority over their children and servants, over Wede:i and other men and women lower in the hierarchy. Brutality toward women was despised, and so far as we can judge from popular literature, women did not consider their husbands to be their oppressors but their patrons and protectors.

The Ezičimi had no cult of virginity, largely because of their belief that a child's qualities were entirely inherited from the father. It was not very serious for anyone to have non-marital sex-- except when pregnancy resulted. This usually had to be handled with payments and gifts between the families involved-- and woe to a man who philandered above his class. The Axunemi had no convenient contraceptive herb like the Cuzeians, but they did use condoms made of animal intestines.

Mešaism disapproved strongly of divorce-- a wife with children could not be sent away, and even if there were no children it required the consent of the king.

Marriages no longer cemented military alliances between nobles, but they remained important bonds between families-- or within them, since it was considered desirable to marry remote relatives. They were still arranged; popular literature testifies to the parents' right to make matches against the child's will, but also to increasing disapproval if they did so-- in the stories it leads to shame and tragedy. Romance on the side was common.

Polygamy was acceptable, though normal only for nobles and kings; it was considered rather greedy for commoners, however wealthy.

The word for perversion (pijuvatudo) derived from pija 'dirt', and reflected the fact that, in premodern conditions, a taste for promiscuity, prostitution, and even particular practices such as oral sex, would almost inevitably lead to disease. If one's dalliances were with social inferiors, so much the worse-- worse than uncleanliness was vulgarity. Prostitution was outlawed (though never eliminated)-- not least because it detracted from the sex on offer at the temples, which rewarded work for the community or the temple, not lust and excess wealth.

The institution of the third sex continued into Axunemi times; indeed, the ewemi were more important than ever. The idea that all men were warriors might have been roughly accurate during the Ezičimi conquest; now it was a retrograde social fiction. Ewemi bureaucrats, advistors, and priests were arguably the core class of the empire. The calculus of power affected the šešedu: as many as a third of boys (but a smaller fraction of girls) were now recognized as ewemi.

By late imperial times, the growing power and numbers of the ewemi, however, strained the social conventions almost to the breaking point. Residual sexism (some of it explicit in religious books and rituals) rankled powerful ewemi; even more resentment was caused by the conventions that ewemi could only marry each other and could not have children. The situation was ripe for a change.

There was also what we might call constitutional opposition, based on the examples of the Ways of Nations: since statecraft had been laid out in this book, any ruler who departed from its precepts could be criticized. Naturally, this did not preclude novel complaints; it was simply necessary to interpret the classic as if one's proposal had once been standard practice. Kings and emperors occasionally executed recalcitrant scholars, but they were never able to squash this sort of dissent entirely.

As a result Wede:i paganism survived in a relatively pure form for centuries. The religion used the Wede:i god names, kept to the Wede:i rites and scriptures, and of course left out Ezičimi racism.

The chief gods were the patron gods of the major cities:

Of these six gods four, though known in the Xengi valley, were of little import there. Much the same is true of Jeor and Tanel, hinting at a wide variety in early Wede:i religion, lost as the hydraulic empires promoted a small subset of gods, generally those associated with the most powerful states, or those associated with astronomical objects, or whose totems had universal appeal (e.g. the bear, Songkana:n).

Wede:i Cuolese totem gen landmark city Bukana:n Bugná~ deer f planet Vereon Yewör Maun Mõ` leopard m river Puro Ö~pelú Śabukma Šaukma swallow m moon Naunai Nàral Je:tun Jécũ coyote m planet Imiri Yežla Buru Büru loon f river Doju Büži Ruźina:n Ružná~ pheasant m star Ažáritar Meniz

Note that the local gods have taken over two of the planets: Vereon from Ražakma, and Imiri from Songkaná~; and that Śaukma is male, not ewimo.

Other well-known gods:

The Cuolese Acöji derives from an alternate Wede:i name Akyauji (honorific + 'beetle' instead of 'beetle god'), while Aksazi derives from Axunašin Xivazi. Also note that Aksazi's totem is not the whale (meaningless to the landlocked Cuolese) but the better-known iliu.

Wede:i Cuolese totem gen landmark Wila:r Wilár hawk m planet Išira Tokna:n Tokná~ carp n lake Van Akru: Akrú lion m the sun Raśakma Ražakma fox m Aklu:ma Aksazi iliu f the sea Losuna:n Lozná~ elk f planet Hírumor Yaujina:n Acöji beetle f planet Vlerëi Jaukaroda Jögroa wolf m planet Caiem Songkana:n Songkaná~ bear m Begong Beong eagle m moon Iliažë Birbi: Bibí owl f moon Ilacáš Akśim Akšũ snake f river Xengi

As a reference, here are the major cities with ancient and modern names. The towns are ordered from upstream down; not coincidentally, the traditional capital of each region is the first listed-- the farthest upstream, thus hardest for the Axunemi to get to.

To the people of Doju and Pronel, their religion was strongly differentiated from Ezičimi and Axunaic Mešaism. They were proud of their antiquity and their national character; they felt that Axunemi Mešaism was full of unholy accretions and pedantic additions; they rejected its disrespectful tales of war among the gods; they disliked its close ties to despotism and considered it to countenance immorality and hedonism.

country Wede:i Cuolese Axunašin Xurnáš Pronel Yewor Yewör Yewor Yuor Yonpelu: Ö~pelú Yompelu Yompeyl Na:iral Nàral Neiral Nirau Doju Yeśela Yežla Yešela Yešila Buruśi Büži Buruši Borauš Melenniz Meniz Melenis Melic

Their own temples and rites had a certain rough grandeur which they praised at the expense of the massive, bureaucratic Ezičimi establishments. And though their society was by no means egalitarian, there were much smaller social gaps between men and women, nobles and commoners, this and that city or region. Even the gods seemed farther off: these small countries, frequently invaded, could not convince themselves that their patron gods were particularly powerful. They were loved all the more for this: a conqueror might occupy the palace, but the gods still belonged to the people.

Historically, we can see that there was a good deal more Ezičimi influence than the locals would like to admit. Newer ideas such as the elaboration of mureši and šaruvi, newer gods, even aspects of millenialism and the New Rites, percolated into Doju and Pronel. The kings created monasteries on the Ezičimi model, and commissioned books of ritual similar to the Dusočuvax. The idea of the third sex was even imported, though it was always much more marginal.

During the period of Jippirasti rule, more than half the population converted to the new religion. For the rest the Wede:i gods remained, but no longer as great players on the cosmic stage. They were godlings now: supernatural allies, bestowers of luck, curses, and visions, clever rather than strong as they helped their followers deal with a world that had become large and hostile. The works of theology and ritual were lost; indeed, writing was almost forgotten, except by a few monks, and scribes employed by the rulers.

The old temples were largely gone: pulled down by the Jippirasti or looted and burnt by invaders. There were new, smaller temples, supported directly by the people, as the nobles were generally foreigners and usually Jippirasti. What waterworks had existed decayed; the gods were no longer needed for this, or to preside over the agricultural year; their astronomical associations were largely forgotten. More than ever they were associated with their animal totems, to the point that outsiders reported that the people worshipped animals.

Especially during the two centuries of the Cuolese empire, they built new temples-- ironically, because no plans existed of the ancient edifices, their model was the classic Mešaist temples still visible in Xurno. The monasteries were given new charters and expanded; the logograms were revived and taught.

Nonetheless, it was hardly possible to simply restore the ancient religion as it was. In the living religion the gods were now little more than culture heroes; re-establishing cults for them would be like instituting sacrifices to Santa Claus. Ancient texts were read with eyes familiar with Jippirasti monotheism and the atheism of Endajué. The monks and scholars assigned to create new state rituals ended up with a form of pantheism.

The divine permeated the world and all worlds. The gods were focus points for the divine consciousness, ultimately unified, but in our very imperfect view acting and warring in the cosmos as separate entities. The actual animals in nature were another manifestation; so were our own instincts and passions: love, reason, justice, creation, aggression, and so on. Ancient rituals could now be re-enacted, enjoyed for their antiquity and cultural resonance, and given new spiritual meaning by the contemporary doctrine.

The revived religion was very successful in reflecting and amplifying Cuolese national feeling, and it has more than held its own against Jipprasti and Endajué, especially among the urban and agricultural population. The pastoral fringe of the country is still populated by nomads, following either Jippirasti or traditional Sainor beliefs.

Philological notes: Čeiy is the Xurnáš name of the country, from Axunašin roz Čebevi 'land of Čeba', that being the Axunemi emperor who began the conquest of the territory. The Verdurians have borrowed this as Čey. The native name is Teô (ô = schwa), from the same source; this gives Tžuro Čeha. For the adjective and the people I use the Xurnáš Čeiyu; the native form is teôr. The language is Teôši.

For reference, here's the table of the major gods with the names in Teôši.

Axunašin Xurnáš Teôši totem gen element landmark Meša Meša Mešö hawk m air planet Išira Evonanu Evan Evonän carp n water lake Van Inbamu Imbamu Ibbäm lion m fire the sun Welezi Elis Weles fox m diamond planet Vereon Xivazi Xiaz Ziväs whale f water the ocean Moun Mun Mu leopard m wood the forests Jenweliz Jeywelis Denwelis elk f emerald planet Hírumor Meidimexi Midzim Mizimek beetle f earth planet Vlerëi Ušimex Aušimex Üšimes wolf m gold planet Caiem Emouriz Emuris Emüris bear m jade planet Imiri Nejimex Nejimex Nedimes eagle m silver moon Iliažë Nejimexi Nejimec Nedimek owl f iron moon Iliacáš Nejimez Nejimes Bivimes swallow n mercury moon Naunai Axun Asu Zentš snake f water the Xengi

The Mnau peninsula was originally occupied by the Eastern Wede:i or De:iju people; they were never incorporated into urban Wede:i civilization, and indeed never advanced past garden agriculture; in the south they were hunter-gatherers. The emperor Čeba began the conquest of the peninsula in 990; the De:iju were so thin on the ground that the only hope of holding the country was to bring in colonists.

For several centuries, Čeba's land (roz Čebevi) was a developing frontier. Life in Čeiy was simultaneously a reward and a punishment: grants of land were made to nobles, while other settlements developed from penal colonies. For centuries the region was simply a set of small outposts remote from each other and from the homeland.

The aim was simply to extend Axunemi territory; but the circumstances of colonization laid the groundwork for independence.

These were united in 1741 as the nation of Čeiy, and were a shining exception to the sorry state of the Xengi plain. Čeiy developed a market economy, devised a Senatorial government, and enjoyed peaceful relations with its neighbors. And for centuries it, alone of the civilized countries, escaped the depradations of the nomads.

Times worsened in the 2400s, when the Gelyet conquest of Axunai and Čisre control over the Littoral eroded its foreign trade. The final disaster came with the rise of Axunai: the remaining Gelyet invaded Čeiy and occupied the capital, Tetäs, while the Skourenes of Čisra occupied Tädda (2625).

Xurno came to the rescue, conquering the country by 2640. To the Čeiyu the Xurnese occupation was more bitter than the plundering of the barbarians-- which was mercifully short. The Xurnese stayed for two centuries, never understanding that they were unwelcome. Were these not fellow sons of Axunai; should they not be incorporated into the new and more glorious empire?

The liberation from Xurnese rule-- accompanied by terrorism and a religious upheaval-- must be put off for another page, on Endajué and its offshoots Revaudo and Bezuxao.

Here's a summary chart of the main periods in Čeiyu history:

from 990 Colonial period 1741 Čeiy united; classical golden age 2625-40 Gelyet conquest 2640 Xurnese occupation 2836 Independence reestablished. Bezuxao domination 2940-63 Civil war 2963 Modern Čeiy

The first difficulty was that colonists came from all over Xurno, with primary attachments to a dozen gods and goddesses. There was no question of choosing a patron god for each new city; all the gods had to be accommodated. And imperial governors tended to be various and prone to return to Axunai after a few years if they could manage it; their patronage was therefore of little importance.

The end result was that cities contained temples to all of the gods, unconnected to each other and only marginally connected to the state. Under imperial rule governors might interfere in matters of succession, or insist that the Dusočuvax be followed; but this ended with independence.

As an institution, religion was therefore weaker than in any other civilized area. The temples had no police power; they were not agents of government; public life and literature were not (as in other Ereláean countries) drenched in conventional piety. There was no punishment for laxity or eccentricity.

This isn't to say that Čeiy believed in what we would call separation of church and state. Religion, like the family, was viewed as a pillar of the nation, and no one had any trouble with officials invoking the gods, basing laws on religious principles, or granting favors to the temples and monasteries. For that matter, the Senate cheerfully established laws about temple practice or even declarations of theological principles.

The weakness of the institution did nothing to impede popular fervor; indeed, the equality of the temples encouraged a sort of buffet approach to religion: people seeking divine favors would hedge their bets by courting several gods.

As in Axunai, the monasteries were the primary place for education, medicine, and inquiry in general. Čeiy however was the site of the first secular teaching institution in Ereláe: the Šivines, named for a pool off the main square of Tetäs. A number of young men of means who were meeting there daily to swim and relax decided to hire tutors to give lectures, starting in the 1850s. It was given a Senatorial charter in 1862, with a grant of land, and developed into a full university-- 450 years before the founding of the University of Verduria.

(The Verdurians retort that their university has been continuously functioning for longer; the Šivines was shut down from 2625-42 due to the Gelyet invasion.)

The Axunemi tendency to explore and populate higher mureši was even more intense in Čeiy, where the cults of the traditional gods were weaker. Magic and other esoteric disciplines were popular. Ideas from Jippirasti and Skourene sages were welcomed; monks and scholars devised elaborate new cosmologies, formed cults, even founded utopian colonies up in the mountains.

Čeiyu thinkers were not individualists in our sense; they still had a strong sense of Čeiy as a nation, and the Čeiyu Senate was venerated as its highest manifestation. But the Axunemi deference to authority and submergence in the community were more and more lacking. The Čeiyu in effect invented privacy: individuals, families, businesses, religious organizations had physical and mental areas of autonomy.

The fatalism and conservativism of mainstream Mešaism disappeared in Čeiy. The Čeiyu were curious and experimental; if at the worst this made them prey to faddism, it also encouraged inquiry. It was believed that truth was best discovered by ešikävu, the adversarial method. Ideally there were two people per side-- one to argue positively, one to argue against opponents; two auditors (empowered to ask questions or to point out errors in any side); and an adjudicator who would announce the truth. The first forms of this appeared in monastic debates, but it was refined in the Senate, and spread to law and education as well.

The position of women was much more favorable than in any Axunemi state. Classical Mešaism valued people for who they were, but the Čeiyu impulse was to value them for what they did. Women worked as hard as men, and bore children as well-- a function of prime importance to a colony.

Marriage was still an arrangement between families, but girls were allowed to reject suitors at whim. The bride also received a gift from the suitor-- property, if possible; and this gift remained under her control after marriage. Polygamy was forbidden; violence against women was severely punished.

At the same time, Čeiy became noted for a certain prudishness. Axunemi culture had never had any great hangups about nudity, but in Čeiy public nudity was unheard of; even art was supposed to be modest. (Inevitably there arose a sub-genre of erotic miniatures for private enjoyment.)