Writing my page on the pragmatic case for liberalism, I promised a page on the moral case as well. This (a tad late) is it.

Now, if you don't agree with me much, you probably won't like this page. Everyone finds their political opponents to be annoying and foolish.

Nous ne trouvons guère de gens de bon sens que ceux qui sont de notre avis.The “What's liberalism” section from the other page applies here. There's no mystery about it: liberalism is the political/economic system the US had from the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt to that of Ronald Reagan; that is, from 1933 to 1980, just under half a century.

We hardly ever find any sensible people, except among those who share our opinion.

—La Rochefoucauld

The major difference since then is that conservatives were able to implement plutocracy instead: running the country for the benefit of the wealthiest 10% rather than for the whole population. The difference is crucial for practical questions (like “why are most people's incomes stagnating?”) but less important for discussing the moral basis of liberalism.

(However, it is important to address those, left and right, who like to pretend that liberalism is more in control than it is. The answer to the question “Why haven't liberals fixed this and that problem??” is almost always “Because we're not in charge.” For the last 35 years, either we haven't had the presidency or we haven't had Congress.)

For foreign readers, liberalism isn't what's called libéralisme in France. It's close to European social democracy. The name comes from Britain, but I'm not saying anything about British politics here.

Summary

An attempt to put liberal principles in a nutshell:- Make everybody better off

- Injustice is disgusting

- Don't be a cynic

- Problems can be fixed

- Don't hold out for perfection

- Use the system

- Capitalism is... OK I guess

- Question authoritarians

- Modernity isn't scary

- Don't lie

- There is no single villain

Make everybody better off

My earlier page made the case that, if you want everyone in the country to be better off, liberalism is the best policy.No mere collection of facts can make that if into an imperative. But this moral principle can: you should want everyone in the country to be better off.

The alternative is that you don't want everyone to be better off. Objections tend to be of two kinds:

- You think only people like you should be better off. Points for honesty, I guess, but a desire to hurt people unlike you is ugly.

Besides, as the pragmatics page showed, general prosperity benefits everyone. A desire to hold back your own prosperity simply to keep others from gaining is... baffling.

- You think general prosperity is less important than something else— piety, sexual propriety, depth of culture, order, the rights of property owners. These sentiments may be genuine, but they're generally an attempt to whitewash the previous category— the assumption is that the disfavored classes are less religious, more licentious, stupider, more dangerous. They aren't, but if it worries you, prosperity is an effective assimilator.

(A few people read my earlier page and thought it was about utilitarianism. Liberalism goes beyond that, but to head off a misunderstanding, it definitely isn't the straw man version of utilitarianism— i.e. “the ends justify the means.” Liberals are very much into common morality and the rule of law, which is why we are so disappointing to revolutionaries.

Injustice is disgusting

Story time

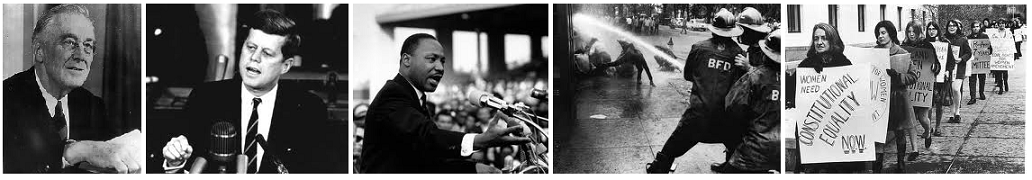

I doubt many people join a movement because they've read its manifesto. Though modern liberalism started with the New Deal, its heart is the civil rights movement. To explain the appeal, I'm going to have to tell some stories. In 1951, a black family headed by Harvey Clark, a WW2 veteran and a university graduate, rented an apartment in Cicero, Illinois— a couple miles southeast of here, in fact. He was hassled and beat up by police officers as he tried to move in. He successfully sued to keep the police from preventing the move.

In 1951, a black family headed by Harvey Clark, a WW2 veteran and a university graduate, rented an apartment in Cicero, Illinois— a couple miles southeast of here, in fact. He was hassled and beat up by police officers as he tried to move in. He successfully sued to keep the police from preventing the move.

Then came the three-day riot, in which 4000 whites mobbed his apartment building, threw stones, destroyed the family's possessions, and finally set fire to the building. Clark himself most regretted the destruction of his piano, which he had bought for his daughter by working overtime.

- Or there's the case of Malcolm Little. While his mother was still pregnant with him, Klansmen surrounded their house and broke all the windows. His father and three of his uncles were killed by white men, one by a lynch mob. His home in Nebraska was burned by another mob. Malcolm's early childhood was hard, but he did very well in high school— he got top grades and was elected class president. One of his teachers asked him what he might do for a career. Malcolm answered that he thought he might like to be a lawyer. The teacher smiled and told him “A lawyer— that's no realistic goal for a nigger.” He suggested carpentry.

Not surprisingly, Malcolm decided that the white man's world was a conspiracy to prevent black progress, enforced with smiles at the top and terrorism at the bottom. Under those circumstances, why not turn to crime? He did, but later he got religion and changed his name to X.

- August Wilson tells a story about his mother. There was a trivia contest on the radio, in the '50s, where the prize was a new washing machine— something she sorely needed. She knew the answer, called in, and won the prize. But when they learned that she was black, they wouldn't give it to her. They proposed giving her a gift certificate to the Salvation Army instead; she could get a used machine there.

- Or Commissioner Bull Connor in Birmingham, who used attack dogs and fire hoses against peaceful demonstrators led by pastor Martin Luther King Jr (1963). King was a Christian minister, and advocated non-violence and even non-resistance to violent provocation; four years later, he was murdered. During the Birmingham campaign, the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed, killing four teenage girls. The Klansman who did it was found not guilty, though he was fined for possession of dynamite without a permit.

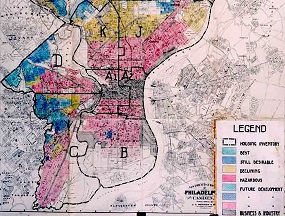

- Clyde Ross grew up in Mississippi, where the law was unavailable to blacks, and whites simply stole any black wealth they wanted. (Ross had a horse when he was ten. White men took it from him.) Ross moved his family to Chicago in 1947, where he could vote and get a house. Regular mortgages weren't given to blacks; instead an operator got him a contract house— where the householder was responsible for all upkeep, but could lose the house if he missed a single payment. It was federal policy to deny ordinary mortgages to blacks.

- James Zwerg, a white divinity student, was one of the Freedom Riders who in 1961 rode segregated buses and refused to sit in the back of the bus. They were met by a mob in Montgomery; Zwerg was held against the wall by a group of men while men punched him and women clawed his face. Some women held up their toddlers so the little ones could attack him too.

- Fannie Lou Hamer was a black woman who dared to register to vote. She was thrown off the plantation where she lived; when she stayed with a friend she was shot at; her house was assessed a $9000 water bill though it had no running water; she was arrested, beaten savagely, and sexually molested in jail.

- Nichelle Nichols was once kicked out of a hotel in Salt Lake City, where she had a reservation, for being black. She couldn't find another hotel, either— she found a family to stay with. When she was working on Star Trek, the guard at one gate in the studio lot wouldn't let her in, for being black. It's really really low to mess with Lt. Uhura.

Multiply by 23 million.

Liberals think this is no way to treat people.

But it goes way beyond that. Some researchers claim that liberals aren't motivated by feeling of moral disgust, but I disagree. Liberals think incidents like these are disgusting. Racism is viscerally wrong, it's unacceptable, and it needs to stop.

Plus, we think it's un-American. Hard work and ambition and service to your country are supposed to be rewarded, not punished. If blacks threatened to do too well, the rules were changed— or whites resorted to raw violence.

What it took

It was a different world in the 1960s. Racism wasn't covert; it was right there in the open, and backed by beatings, bombings, and death. White supremacy was assumed by the lowliest Klan thug and enunciated flutingly by William F. Buckley (“The central question... is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes—the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race”).But things have changed, right?

Right! They changed because of hard work by liberals:

- Legal challenges, such as Thurgood Marshall's successful 1954 Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, which declared school segregation illegal.

- Peaceful demonstrations, e.g. King's boycott of the segregated buses in Montgomery.

- Black nationalism, as preached by Malcolm X and others— important to get blacks to stand up for themselves, and also as a reminder to whites that if King's nonviolence didn't work, there were alternatives. (Not that Malcolm X himself actually used violent methods— but there were other activists who were open to that.)

- Federal support to ensure the rights of blacks to vote, move where they liked, and have equal educational opportunities.

- Affirmative action to prevent segregation and to increase opportunity for blacks.

- Economic aid for the poor (which included vast numbers of whites).

- Journalistic coverage, which raised awareness of the issues and shone a spotlight on the horrible abuses of the racists.

And more— you can find the full history elsewhere, and you should; it's a fascinating story and offers essential lessons on how a social movement happens. Some random books that have helped me understand it: King's Stride Toward Freedom and Why We Can't Wait; Malcolm X's Autobiography; John Griffin's Black Like Me; Dick Gregory's The Shadow That Scares Me; Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird; Alice Walker's The Color Purple.

One of the best contemporary guides is Ta-Nehisi Coates. His article on reparations is essential reading, especially if you think there's no problem any more. See also his reading list.

An important note: I used historical stories above in order to explain the historical context for liberalism. I don't mean to suggest that racism is dead. In recent years we've had plenty of reminders that being a young black male in possession of a bag of Skittles or a toy gun is considered by many to be a killing offense.

The worried white man

A lot of people accept that the mistreatment of blacks was wrong, but any actual attempt to mitigate it was bothersome. We can imagine a dialog:Worried white man: If you work hard you'll get ahead.A: No we won't; you closed off everything but menial work, and if we achieve anything, it can be simply stolen by whites.

WW: Did you try asking really nicely for reform?

A: Yes. We tried that for a hundred years. Nothing happened.

WW: You should have voted for politicians who would help you.

A: Blacks can't vote in the South, remember?

WW: Uh... we established the courts to redress grievances... did you try that?

A: Yes, that was the first successful tactic. But court judgments are ignored, if the authorities don't like them.

WW: Surely passing laws would be better than demonstrations?

A: We tried that constantly, but they were defeated by the reactionaries in Congress. It wasn't till there was pressure from the demonstrations that Johnson defied his own party to pass them.

WW: OK, but these demonstrations were so provocative.

A: That's the word exactly. We need to provoke change.

WW: But demonstrations invite lawlessness and violence.

A: There is no violence in Dr. King's movement, except what's done against us.

WW: Couldn't you at least suppress the Black Power people? They scare us.

A: Tell you what, we won't resort to revolution if you can show us that peaceful agitation works. Like, say, make sure that Dr. King doesn't get shot.

WW: Oops.

Oppression becomes privilege

Oppression is never just a matter of Sauron treading over the little folk. One of the things about oppression is that it corrupts both the oppressor and the oppressed.People used to defend white supremacy (and male supremacy) openly, but even in its heyday it was rationalized and euphemized. The white supremacist doesn't want to admit that he's dehumanized blacks. He concocts a worldview where they deserve their lowly status, or they're happy with their lot, or they should be.

That worldview persists even when overt racism doesn't. A situation can remain unfair, prejudice can still be widespread, even if the dominant class deplores overt oppression and thinks they've gotten past it. Oppression turns into privilege.

An oppressed class also, understandably, gets cranky. Activists will express that anger. This is actually an important step in breaking internalized oppression, but it can be disturbing or off-putting for outsiders.

To keep this page short, I've made a separate page going into privilege in more depth— what it is, why you can be a nice guy and still contribute to oppression, and answers to common objections.

Everything else

I won't go into similar detail on feminism, LGBT activism, etc., but I'll give you a general principle or aspiration that covers almost everything: treat everyone like a human being.John Rawls had a nice way of visualizing this: imagine that you have to design a society and then live in it, but you don't know what sex, race, class, skill level, or religion you'll end up as. Pretty evidently, your self-interest would point to the same outcome as justice: you'd make it so that having a decent life didn't depend on any of these variables.

It's also the teaching of Paul: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” If sex and race mean nothing to God, you can't build an ideology of male or white supremacy... except of course by ignoring the Bible.

It's also in Isaiah: “Is this not the fast which I choose, to loosen the bonds of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke, and to let the oppressed go free, and break every yoke? Is it not to divide your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into the house; when you see the naked, to cover him, and not to hide yourself from your own flesh?” And these aren't isolated passages; God is a liberal.

A corollary is that justice doesn't mean reversing the oppression. Feminism doesn't aim to replace male supremacy with female supremacy. The civil rights movement doesn't aim to place blacks on top.

Don't be a cynic

The great theoretical ally of the conservative is apathy. “That's too big a problem to solve. That's politically impossible. You can't change human nature. Live in the real world. Things are always bad. You're an ivory-tower idealist.”The radical left-winger or anarchist sounds the same, though. “The problem is capitalism. They'll never allow real change. The system is broken. It's no use marching or writing letters or winning elections. The liberals are a joke. Don't ask us for solutions.”

The liberal response is: change is possible, but it takes work.

- In 1995, the idea of gay marriage in the US, or legalized marijuana, seemed impossible. Universal health care looked like it was dead in the water.

- In 1980, the idea of smoking bans, or halving the crime rate, seemed impossible.

- In 1935, the idea of letting blacks vote seemed impossible, and looking around the world, it was hard to imagine the defeat of totalitarianism. It was assumed that China and India would be starving-poor forever.

- In 1900, the idea that the largest class in society need not be the poor was unimaginable, and the idea of women voting was considered laughable.

- In 1840, the idea that slavery could be abolished in the US was dangerous extremism.

- In 1750, people would be astonished and disturbed to hear that in the future most countries would be republics rather than kingdoms, that large-scale wars would be rare, that poor men could vote, and that people could freely choose what religion to believe.

Problems can be fixed

Conservatives like to find something going wrong and imagine that they've refuted liberalism. Radicals feel that any problem shows that the whole system must be thrown out.None of these moves bother liberals, because we believe that problems can be solved. Do divorce laws unfairly favor mothers getting sole custody? That can be changed (and in fact there's been a solid movement toward joint custody). Was the Obamacare rollout an excruciating mess? It sure was, and it got sorted out. Is there a systemic problem of sexual harrassment, or police militarization, or NSA overreach? There is, and we need to fix it.

Another way of putting this is that we were all taught in school that free enterprise works for everyone, democracy gives us all a voice, everyone has civil rights, and any child can become President. We grow up and discover that it's not so true. The system is broken in big and small ways. But as an ideal, it's great! There's lots of evidence that problems can be fixed; there's no evidence that none can be fixed. So let's work on them.

Don't hold out for perfection

Idealism— such as that found in the last paragraph— is great, and necessary to get anywhere. But we can get hung up on the ideal, such that we get furious at any half-measures and even oppose them.Radicals and moderates exist in an uneasy balance. For any cause, we need the radicals and their energy— and their ability to focus attention on a problem. But on their own they frighten the undecided, attack each other, go off on dubious tangents, and burn out in failure.

An example is universal health coverage. Worldwide, the cheapest and most effective way to provide this is what Canada has— a single-payer system. That wasn't possible here, so Obama pushed through a market-based system.

If you're a radical in any one area, this can be infuriating. You want full-out, pedal-to-the-metal action on your issue right now. For example, not a few LGBT activists hated the whole gay marriage push. They wanted to demolish the patriarchy, not grab one of its perks. But let's look at the scorecard: twenty years later, a) gay marriage is happening in every state, and b) the patriarchy hasn't been demolished. Which approach actually accomplished something?

More subtly, but importantly: didn't this approach at least seriously damage the patriarchy? The younger generations don't just accept gay marriage; they think that prejudice against queer sexuality is mega-stupid.

Now, there's a very human age progression here. The French always seem to express these things well:

Mon fils a vingt deux ans. S'il n'était pas devenu communiste à vingt deux, je l'aurais renié. S'il est encore communiste à trente ans, je le ferais alors.Or as someone put it on Metafilter recently: “I don't like incrementalism. But long term, it seems to be the thing that works most reliably.”

My son is twenty-two. If he hadn't become a communist at 22, I would have disowned him. If he's still a communist at 30, I'll do it then.

—Georges Clemenceau (probably)

Use the system

This one is aimed at both left and right. The radical left is in love with revolution— tear down the system and start over! Conservatives are terrified of revolutions— they're afraid that liberals secretly want to hang them from the lampposts.

This one is aimed at both left and right. The radical left is in love with revolution— tear down the system and start over! Conservatives are terrified of revolutions— they're afraid that liberals secretly want to hang them from the lampposts.

Marxism was a generalization of the French Revolution. Under an absolutist system, it's natural to think that power naturally works absolutely, and that to fix things, the oppressed classes need to take power and rule absolutely. We've had 200 years to test the idea, and the track record is not good. The French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions soon ushered in tyrannies. If you took power with guns, this will in itself devastate the economy; plus, you'll want to solve every problem with guns. Guns turn out to be not very good at creating a country where you'd actually want to live.

The American revolution emerged from the English bourgeoisie— that is, English cities, which were used to elections, laws, and legal rights. Even when they decided to rebel against the Crown, Americans decided to do so in Congress, following legal procedures.

The law is not lovely, but it's tended to work far better for both general prosperity and for guaranteeing rights than revolution. Law is inherently anti-authoritarian... even when it derives from authoritarian systems... because it allows institutions to be called out on violations of their own law, and because rights granted to the few become a precedent for extending them to the many.

Liberals have often resorted to the law, to overturn school segregation, to make schools and police and institutions honor civil rights, to give the Bill of Rights teeth, to overthrow discrimination against gays and lesbians, to rein in corporate abuses.

To implement your program without revolution, you need to win elections. In practice, this means you have to find ways to appeal to the majority. That may mean making compromises with the oppressors— as James Galbraith points out, progressive regulation is generally made by an alliance between progressives and the top-performing companies. It's the poorly run companies that hate regulation, because they don't know how to afford it.

“Get a majority” isn't just effective tactics in the system we happen to use; it's also our best guard against making terrible mistakes, of the sort that produce terrorism and/or concentration camps. It's unjust to impose (say) a new economic system on a population that doesn't want it. If the majority doesn't want it, they may in part be deluded or propagandized, but you'd better also consider the proposition that they see a flaw in your utopian scheme that you're papering over. Or that you simply haven't worn out the shoe leather working to bring your ideas to people unlike yourself.

Question authoritarians

As a result of some of the above tactics, liberals have made very effective use of government and law. In reaction, we get libertarians who decide that the worst evil is government itself. This turns out to mean “government doing liberal things”— i.e. regulation, social spending, racial integration, preventing depressions.This is a historical irony, because generally the reactionaries have been in charge, and liberalism has had to oppose and provoke them. As late as the '60s, question authority was a left-wing trope; conservatives were for Law 'n Order.

Nonetheless, liberals aren't simply for “big government”. Government is a tool that can either advance or restrict people's liberty and prosperity... or more likely both at once. Big government has been used against liberals— from J. Edgar Hoover to the Patriot Act to stop-and-frisk laws to the drug war to anti-gay laws to the voter suppression movement to abortion laws to police intimidation.

But I'd update the slogan a bit. Most of the time, the problem isn't authority in the abstract; it's authoritarians— people who identify with authority and want to use it to enforce conformity, and who follow their own leaders no matter what bizarre and sociopathic directions they take. These people are trouble when they take over churches or political parties or corporations. Evil leaders could do little if they weren't backed by a crowd that follows them blindly.

Capitalism is... OK I guess

On the pragmatism page, I argued that no political/economic system has done so well for so many people as liberal capitalism. There are some good reasons for this: it allows more social mobility than aristocracy; it has a stake in widespread education; it does better the richer people are; and multiple decision points allow for more creativity and less central control.However, you only have to keep your eyes open, and look at history, to see its many failures. The owners/managers' pay gets out of control. Corporations will put filth in your food, defraud you, poison the environment, and avoid paying a living wage if they can get away with it. Capitalism needs activist consumers, workers willing to organize, a nosy media, and a strong government to make it work for the population as a whole. Again, see that page to see how things are worse for 90% of us now that liberalism has given way to plutocracy.

The 1% would rather we not notice all this, so we're barraged with propaganda in their favor. “The market will solve all problems” is code for “We hate government activism that favors the 90%.”

Other folks, of course, think that capitalism is evil. But you know, working alternatives are hard to come by. Premodern societies were miserable for everyone except the elite. Fascism and communism were disasters. (See question authoritarians above.) Anarchism is at best untried, and at worst seems completely unprepared to handle human violence and oppression.

If you have some radical ideas besides “throw out everything”… I'm not necessarily against them, and I might even be convinced. My personal bugbear is the CEO system: I think we've kept monarchical rule in corporations long after realizing that it's a terrible system for governments.

I notice a lot of people on the left in despair about capitalism. Often enough what they blame on capitalism is better blamed on high density or modern technology. But the main problem is that they came of age after 1980, so all they've seen is plutocracy. If you want a much more egalitarian world, let me suggest two words: higher taxes. For fifty years, we had a system where the 10% were held under control, and all deciles got richer. The key way conservatives destroyed that system was by slashing taxes.

Modernity isn't scary

A lot of the opposition to liberalism is rooted in a fear of the modern world. People get alarmed at- sex

- minorities

- foreigners

- irreligion

- cities

This isn't to say that these fears were always illusory. A strong focus on chastity made more sense in a world with terrible hygiene, with rampant STDs, and without contraception. Even a fear of foreigners was understandable when large numbers of outsiders meant that you were being invaded and all your freedoms were at risk.

It's hard for many people, but we have to distinguish the irrational and rational parts of traditional morality. We also have to recognize that large parts of it were, very frankly, designed as propaganda to allow the powerful to stay on top. Sexual morality wasn't all about good health; it was also based on a fear of female sexuality and a desire to control women.

While we're here, I want to counter the conservative perception that liberalism is anti-religion. Quite the opposite! A large fraction of liberals are Christians. Blacks and Hispanics are mostly Christians (and recall that both Dr King and Malcolm X were preachers), but there's a lot of liberal white Christians too. I came out of that background myself... indeed, my political beliefs were deeply affected by what I found in Christianity about God's identification with the poor, Jesus's commands to help the needy and his disdain for Mammon, and the Christian emphasis on service, humility, and love.

Don't lie

There was a time— I call it “1976”— when conservativism seemed like it could be a pragmatic, business-oriented counter to a liberalism that had perhaps been unchallenged for too long. It was useful to be reminded that capitalism works better than central commisariats in allocating production, that bureaucracies aren't the only way to solve problems, that allowing cities to decay into chaos wasn't doing anyone any favors.But conservativism has been taken over by what used to be its radical fringe. I've already made it clear that I disagree with them morally, but beyond that, what I object to is their routine mendacity.

If you think that Obama greatly increased the size of government, or wasn't born in the US, that the Bush tax cuts created jobs, that Reagan never raised taxes or amnestied illegal aliens, that the economy did better under Reagan than Clinton, that welfare mainly went to black people, that the Civil War wasn't about slavery, that people who don't pay income tax don't pay any other taxes, that voter fraud is a problem, that affirmative action means less whites are going to college, that crime is increasing because of illegal immigration, that the US is being taken over by Muslims, that the planet is not heating up— well, you're just wrong on factual grounds; look it up.

Conservative ideology has also had a terrible track record in its prophesies of disaster (when Democrats are in charge) or utopia (when Republicans are). They've been predicting hyperinflation for years: didn't happen. They thought the Iraq war would create a happy pro-US democracy on the cheap: they were wrong. They were sure Obamacare would raise health costs: it hasn't. They assured us that lowering taxes would increase government revenue: look at Kansas, or the whole country under Bush. They told us that Clinton's tax increase would sink the economy: we had a huge boom and a budget surplus.

Then there's the completely cynical flip-flops. Back in 2002, Greenspan lectured Congress on the dire consequences of... that budget surplus. Bush's deficits became a huge problem only when they became Obama's deficits. Similarly, Mitt Romney created a health care plan on conservative principles, backed by conservative think tanks: private insurers, coverage for all, an individual mandate, and subsidies for the poor. The plan was copied nationwide, even designed by the same people— and suddenly it became liberal tyranny, because it was now Obama's.

The white supremacists of the 1950s were despicable, but at least they were honest in their aims. As open racism became less acceptable, conservatives turned to covert racism. Too many nice-sounding conservative policies are just red-white-and-blue flags draped over hatred of blacks, women, and gays. E.g. calls for “smaller government” always turn out to mean reducing programs that benefit blacks and/or the poor; it never means less control of women's bodies, or an open immigration policy. The “tax revolt” of the 1970s occurred when there was a threat that black schools might get the same money as white ones. We hear all about gun rights, except when a black man get shot.

I don't think this is as much of a problem on the far left, but here a related principle comes into play: See how things work in practice. This applies to both how things work now, and how new proposals fare when they're tried out. I see a lot of activists blaming Obama or the Democrats for not getting things done, when the reason those things weren't done was the Republican-controlled Congress. And the biggest reason we have that is that young liberals don't bother to vote in midterm elections.

Similarly, as things are tried, we need to monitor them and make sure they work. Most people left of center believe in some form of redistribution. Which form works best? This can't be answered by ideology; you have to look at each option, check the cost of implementation, follow the money, eliminate abuses. A reasonable opposition party might help uncover the problems, but since we don't have one, we have to monitor things ourselves.

There is no single villain

On my page against libertarianism, I mentioned that single-villain ideologies are always trouble:

On my page against libertarianism, I mentioned that single-villain ideologies are always trouble:

The advantage of single-villain ideologies is obvious: in any given situation you never have to think hard to find out the culprit. The disadvantages, however, are worse: you can't see your primary target clearly— hatred is a pair of dark glasses— and you can't see the problems with anything else.The world is always obviously messed up. Single-villain ideologies attribute this to one cause: government, or capitalism, or communism, or liberalism, or religion, or irreligion, or white people, or non-white people.

You can always make a case for these villains, because they're large things with millions of people involved, and many of them have done bad things. But it's foolish, because villainy is everywhere. No group of people, no political party, no belief system is immune. And if, God forbid, you had a revolution and had the power to exterminate your favorite villains, you'd soon discover that human misery remained, and indeed increased.

If someone reads the news and everything confirms his opinion that his favorite villains are truly bad and insane... he doesn't have an insight into the world, he has mental blinders on. He's simply cherry-picking the data, or being careless about causation.

Some habits that can help insulate against this sort of thinking:

- Wide experience. If you're looking at some bad thing... how did it play out 100 or 200 years ago? How does it go in the US, Europe, China, Latin America? A lot of common political opinions turn out to be very parochial, temporally and spatially.

- Check your theory against how political power actually operates. I've heard both conservative and radical-left conspiracy theories that fail to recognize the simple fact that the US Congress is controlled by the Right. (The conservatives were sure that feminists somehow can get any law passed; the leftists were convinced that Obama could somehow pass laws without the House.)

- If your villain is “capitalism” or “liberalism”, check the past before they existed, and see if it was really so great. In the present, consider neutral causes before assigning it to your enemies.

- Look for the counter-error. You may be righteously opposed to some political course of action; that doesn't mean that any alternative to it is good. The opposite of a bad policy is often also a bad policy.

Getting stuff done

It's been a long-time joke that liberals are ineffective:I don't belong to any organized political party. I'm a Democrat.Being a liberal doesn't mean that we're happy with liberal leaders or politics! No one was able to get excited about Michael Dukakis.

—Will Rogers

But along the way, we got food and drug regulation, anti-monopoly laws, votes for women, the New Deal, Social Security, progressive taxation, the GI Bill, votes and education for blacks, the women's movement, the environmental movement, universal health coverage, and gay marriage. And we whupped Hitler's ass.

At any given moment, things look dire and our leaders look gutless. But over time we get stuff done.

—Mark Rosenfelder, April 2016