| March 2019 |

|

| Tiphaine Rivière: Notes on a Thesis | |

Studying in Paris seems like a dream. A friend of mine did it, and reported excitedly that there were exams only at the end of the year, so you could spend most of your time exploring the city and trying to get laid. (Cross-linguistic note: to get laid is very different from being laid.)

Studying in Paris seems like a dream. A friend of mine did it, and reported excitedly that there were exams only at the end of the year, so you could spend most of your time exploring the city and trying to get laid. (Cross-linguistic note: to get laid is very different from being laid.)

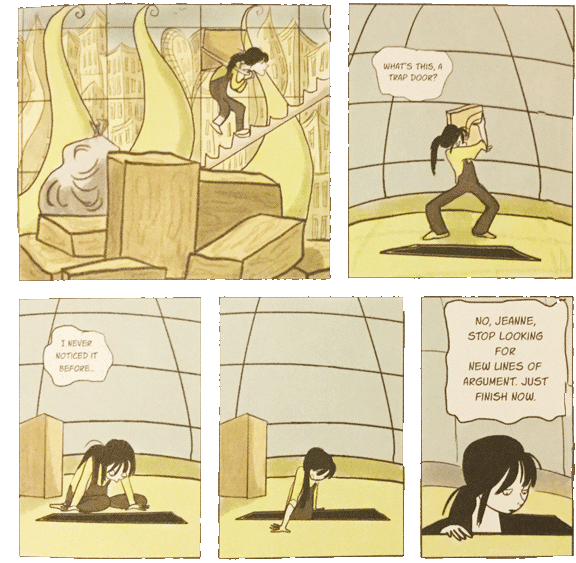

But he was an undergrad. Based on this book, being a grad student is no picnic. Jeanne Dargan, pretty obviously an authorial stand-in, is thrilled to stop teaching lycée students and be accepted into graduate school, writing a thesis on Kafka under the supervision of a leading Kafka scholar.

But, she can’t seem to get a word down. It’s not that she can’t to anything, but there’s always something to do besides writing the thesis itself. There's always one more book to read, one more avenue to explore and integrate into the 69-page outline for her thesis. Plus her advisor is never available, her parents are increasingly unsupportive, and her boyfriend is getting tired of never doing anything except getting updates on her research.

And then there are the financial concerns. University is free, but she still has to pay rent. She teaches a class on medieval literature— not her specialty, so she does it staying just one step ahead of the students— and finds that the university has some stupid rule, which it only discovers at the end of the term, that means she can’t get paid. Obviously France needs a bit more social democracy.

All this is played as light comedy, but the book really shines when Rivière finds visual jokes— e.g the medieval lit class is depicted as a bunch of tigers, which become kittens when she gives them a choice they like about the final exam. Her thesis is represented first as an elegant Baroque palace, which morphs and distorts over time into a crazy architectural monstrosity.

Now— spoiler— Jeanne ends up finishing her thesis, though it takes five years instead of the expected three. The real Tiphaine worked on hers for almost four years, then decided to hang it up and draw BDs instead. I’m torn about this: it’s satisfying for the story that Jeanne finally succeeds, but the author’s story sounds more interesting. Plus, how does it compare, writing a few hundred pages about Kafka, vs. writing and drawing a 180-page graphic novel? (But if she had pursued her actual story, the comic would have had to be far longer...)

I like the art style: when she wants to, she can draw naturalistically; but she always gives priority to the emotional range afforded by a more manga style. I also like the way she occasionally switches narrative viewpoint, especially when it comes to her advisor... obviously a man who long ago lost any interest in dealing with actual students.

I’ve read some reviews which mostly talk about how much Rivière has nailed the PhD experience. I can’t comment on that, but it’s a great debut comic. And she already has a new one out, L’invasion des imbéciles, which is supposed to be amusante et réflechie. It’s much harder to get that second academic book done...

One more linguistic note: this comic is available in Chinese; her name in Mandarin is Dìfěinuó Lǐwéiāiěr. If I ever get published there I’ll ask if I can just be 玫瑰田 (Méiguītián ‘rose field’) rather than have them attempt Rosenfelder.

| Charles Moulton: Golden Age Wonder Woman | |

Just as the early Batmans have been collected in enormous Bat-volumes, you can now read the first 800 or so pages of Wonder Woman, written by Charles Moulton (pen name of William Moulton Marsden) and drawn by Harry G. Peter.

Just as the early Batmans have been collected in enormous Bat-volumes, you can now read the first 800 or so pages of Wonder Woman, written by Charles Moulton (pen name of William Moulton Marsden) and drawn by Harry G. Peter.

As you may have heard, Wonder Woman is an Amazon, the princess of Paradise Island, inhabited only by immortal women. One day a plane crash-lands there, with its pilot Steve Trevor. WW nurses him to health and falls in love with him, and leaves her home to help him win World War II.

She debuted in All Star Comics #8, published in October 1941, but dated Dec./Jan. Steve is in military intelligence, so she is immediately plunged into foiling Nazi spies, though these are at first hard to distinguish from the gangsters her colleagues were fighting until the war began. Like gangsters, the Nazis have nearby bases to infiltrate and an unlimited supply of mooks; the main difference is the German accents.

To stay close to Steve, WW takes the identity of his nurse, Diana Prince— she bribes the real Diana to go away; the lady is happy to do it since she wants to marry her boyfriend who’s taken a job in South America. When Steve gets better, Diana becomes the secretary of his army boss, which sets her up in a neat romantic triangle with herself: she's in love with Steve, who only has eyes for Wonder Woman. Diana is depicted as quite capable on her own, unlike (say) Bruce Wayne or Clark Kent. (Strangely, she has shorter hair than WW. I suppose she binds it up. We also see this trope in movies— midcentury American males had a real fetish for women “letting down their hair”.)

She soon acquires both a female auxiliary and a female recurring villain. She befriends Etta Candy, a fat girl at a women's college, and Etta and her "Beeta Lamda" sorority faithfully help out whenever she needs a squad of unlikely-looking girls to swarm a Nazi base. The villain is Baroness Paula von Gunther, who has an army of slaves and a maddening way of coming back from the dead.

There are similarities with Golden Age Batman: the fast-paced stories, with plenty of fisticuffs and a ridiculous plot solved each issue; the merely adequate art; the over-reliance on narrative captions; the utter disinterest in the actual nature of criminals or spies. But Moulton is a far better writer: WW is a more interesting character, showing a wider range of emotion; there's more of a sense of social reality (e.g. some early stories which sympathize with oppressed workers); and more use of humor.

Plus, about halfway through Volume 1— or, fall 1942— the plots become batshit insane. There’s one where WW, Steve, and Etta travel astrally to the planetoid Eros, which is run by women, and has a prison system so humane that no one wants to leave it; when one prisoner is found not guilty, she is so upset at leaving prison that she starts a war. There's a whole mini-series where the main antagonist is Mars, the ancient God, who, um, lives on Mars and runs Tojo and Hitler by whispering to them in astral form. It's silly, but after a couple of decades of grimdark, it’s more fun than Batman's Parade o’ Psychos. At the same time, Moulton, unlike Bob Kane, can fairly regularly come up with a story that’s actually moving (e.g. acts of heroism from victims of the supervillains, or an arc where Baroness Paula is successfully reformed).

Moulton was pretty feminist for the 1940s— though perhaps the war helped; victory meant putting aside prejudices against working women. WW has no trace of any deference toward men, and delights in her own intelligence and athleticism. More interestingly, perhaps, her example makes Etta almost as fearless. Her choice of high heels is a little less defensible, but I guess she has super-balance and super-ankles among her other powers. The stories are nowhere near as progressive on race: even sympathetic foreigners (e.g. Chinese) speak in abominable accents and (if male) are as ugly as the artist can manage.

Moulton's personal life was unusual— he was polyamorous, with a stable relationship with two women. (Indeed, after his death, the two women stayed together for nearly 40 years.) He was apparently into bondage, and this is in fact Wonder Woman’s one weakness: if she lets a man weld her bracelets together, she loses her superhuman strength. Villains often tie her up without this step, which makes it a game for her— usually it means they'll take to their secret lair. None of this is presented lasciviously; on the other hand, there’s a weird little story set on Paradise Island where some Amazons chase others dressed as does and tie them up. That’s pretty kinky for 1943.

I keep rewriting the end of this review, because it keeps turning into an essay on the history of superhero comics. In brief: the Golden Age is overblown. It has the advantages of enthusiasm and earnestness, but its heroes— including Wonder Woman— are a little square. They lack the Marvel touch: human failings and human problems. When it comes to social problems, their heart is in the right place, but they can’t even get to a political analysis, much less a structural one. And if you answer that pop culture aimed at teenagers isn’t going to go deeper— it did, in detective fiction, science fiction, and satirical comics like Mad. And by the ’70s the superheroes even started to catch up.

Can’t have a review without some historico-linguistic pedantry. Moulton’s WW comes from Paradise Island, but later on DC renamed it Themiscyra, after Θεμίσκυρα, a city on the northern coast of Anatolia, where the Greeks placed the Ἀμαζόνες. Neither word has a convincing etymology, and both were probably borrowed from outside Greek. The ancients, like the DC writers, loved the idea of an exotic nation of warrior women. They’re probably an exaggeration of the Scythian nomads north of the Black Sea, who did have fighting women: up to 20% of Scythian warrior graves contained women, buried with armor and bows. Nomads, contrary to what certain fantasy authors believe, tend to be far more sexually egalitarian than agriculturalists. The Persian emperor Cyrus died fighting a Scythian tribe led by a queen, Tomyris.