| July 1996 |

|

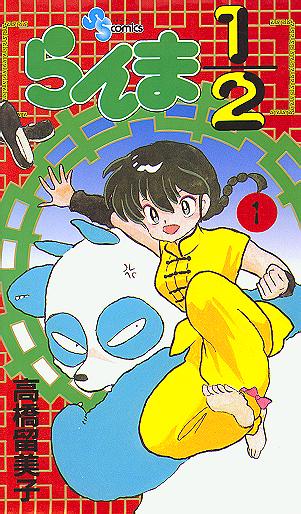

| Rumiko Takahashi: Ranma 1/2 | |

Ranma Nibunnoichi (Ranma 1/2) is really adorable: Ranma is a boy who turns into a girl when splashed with cold water; warm water turns him back into a boy. (These are two separate words in Japanese: mizu and yu.) His father is more unfortunate: he turns into a panda and back.

All that, plus the tribulations of being a teenager. He lives as a guest at the Tando "school of martial arts and indiscriminate grappling", and is theoretically engaged to the youngest daughter, Akane, who doesn't like boys (her sisters figure she should like Ranma because he's half girl). And when all that flags, there's plenty of martial arts action...

All that, plus the tribulations of being a teenager. He lives as a guest at the Tando "school of martial arts and indiscriminate grappling", and is theoretically engaged to the youngest daughter, Akane, who doesn't like boys (her sisters figure she should like Ranma because he's half girl). And when all that flags, there's plenty of martial arts action...

You can learn as much from pop culture as from Leetrachoor... Ranmais like a textbook in sex relations in modern Japan. Takahashi's girl characters are plucky and independent-minded; and yet the image of girls is still sweet and tender-- Akane is a martial arts wizard, but her sisters hasten to assure Ranma that she's a "sweet girl". It also seems that girl-boy friction lasts a bit longer in Japan-- Ranma and Akane, freshmen in high school, are still not sure they like the other sex. (We're dealing with images, not reporting, of course... but people's images of themselves are a part of culture too.)

The sex-change business is treated, in a sense, naturalistically, and allowed to create sexual tension (e.g. "upperclassman Kuno" falls in love with female Ranma, while hating male Ranma), but Takahashi neither descends into erotica (despite an occasional nude shot) nor into really forbidden territory (the sex changes are allowed to get the characters into embarrassing situations, but not into bisexuality).

There are sharp differences between men's and women's Japanese; I'm told that Ranma always talks like a boy, except when he wants to pass as a girl (he finds it's good for cadging freebies from the local food vendors).

My enthusiasm has flagged just a bit on learning that Ranma runs to 38 volumes (~ 6000 pages) in Japanese. And the story evidently gets more wacky, with yet more accursed characters and bits of magic-- and apparently the love story isn't completely resolved even over all that time. (Seven volumes are available in English.)

(I've also seen the first two TV shows, which follow the comic pretty closely, but don't work as well. Comics are a fast medium; the video version drags. Take the last panel on vol 1 p 58: with four rapid-fire balloons; it registers in about three seconds, and is very funny. The same sequence on video takes a quarter of a minute or more, and the joke just can't sustain the elongation.)

This was my first plunge into manga; it's interesting to see a different comics idiom. Everything has sound effects, for instance, even shrugs and the sparkling of teeth-- kind of like Bill Nye the Science Guy. The faces are enormously expressive, à la Jaime Hernandez. And those huge eyes... Some things I haven't quite figured out, such as why people wave fans around when they're drunk.

Takahashi seems to be extremely prolific; she also does Maison Ikkoku, Lum / Urusei Yatsura, Mermaid Forest, and Rumic Theatre. I've only read the first of these, a light comedy about the residents of a seedy apartment house. The characters here are college age, and the focus is on romance... again, it's interesting to compare mores. For one thing, although the possibility of sex comes up, it's treated as rather scandalous; it seems to be hard to get even a kiss out of the apartment manager, the luscious Kyoko... even though she's actually a widow, and thus sexually experienced. It's also interesting that the main characters, Kyoko and Yusaku, both have insufferable parents, and the book's sympathy is definitely with the kids.

| Will Eisner: The Spirit Casebook; Life on Another Planet | |

The Spirit is basically a Marlowe-style detective, who's pasted on a few superhero conventions as he would a fake moustache, merely to gain an entrée onto the '40s comics page. Eisner's real interest is the endless possibilities for human corruption (and, once in a while, redemption) in the big city. Eisner is an artist who seemingly can't draw a straight line: faces are curved into caricatures of the grotesque or the gorgeous; clothes rumple, walls are seedy, the very ground squishes underfoot. And his human beings, too, find it hard to stay straight. If only they'd listen to the Spirit's admonitions-- but they don't, and some elegant little doom catches them.

The Spirit tales seem at first like trifles; there doesn't seem to be much more to them than to any E.C. story. In fact they're almost all little gems of macabre storytelling: strong writing matched by inventive artistry, prose and plot better than they have any need to be, and very frequently pushing the edges of the medium (tho' never gratuitously). You can stare at his splash panels alone for hours.

Life on Another Planet (1983) demonstrates that the same inventiveness and skill remains; yet all in all it's not a very good story. The virtues of a seven-page Spirit story become vices in a 128-page novella: slapdash science, garish characters, heavy moralism. The plot doesn't seem enlightening, only busy; I don't "truly care about" the characters, as the book jacket promises; they're almost all simple variations on greed. And the graphic innovation of dispensing with panel boundaries doesn't help; the book is messy enough as it is-- it needs discipline, not a new dimension to seep into.

In general Eisner's later stuff affects me like Woody Allen's: you see the ambition, and indeed the top-drawer talent, and you wonder what's misfiring, why we see a series of good works but not masterpieces.