| September 2000 |

|

| Scott McCloud: Reinventing Comics; online comics | |

Scott McCloud didn't invent comics theory, but he served up a big tasty portion of it in Understanding Comics, in 1993. This was a remarkable work, not only because it had something new to say to almost all of us, but because McCloud wrote about comics in comics. This was arguably a bit of grandstanding (should painting theory be painted? should music theory be sung?), but it worked; it showed McCloud's commitment to the form, allowed the concepts he was explaining to be immediately demonstrated, and showcased McCloud's sly sense of humor.

This year's Reinventing Comics begins by explaining that it's not exactly a sequel. It's just as well; it's nowhere near as accomplished a book.

The first half is basically a screed on the sorry state of American comics. The main problem here is breeziness. He covers women in comics, for instance, in five pages, and gay and lesbian comics in three panels. He says all the right things, but the speed of the treatment conveys the opposite message. A few wordless disconnected images don't offer much motivation to check out the works; compare the extended treatment and lengthy extracts devoted to Jason Lutes's Jar of Fools. (An exception is an intriguing couple of panels from Carla Speed McNeil; but even those simply stand out for their own quality, without any help from McCloud.)

The second half is an exploration of the use of computers to create comics-- and more importantly, to distribute them; McCloud thinks the near-infinite bandwidth of the Web, plus micropayments, could be the saving of comics... if creators remember to develop comics, and not half-assed attempts at the animated cartoon.

This section, by the way, makes it clear that McCloud is-- in the terms he introduced in chapter 7 of Understanding Comics-- a formalist. What really gets him going is messing with the medium itself. He's basically spent the last few years on a computer binge-- not merely playing with the new toys, but figuring out how they should change the medium itself.

There's plenty of interesting ideas here; but I finished the book rather frustrated. The basic problem: For the first time I found myself doubting McCloud's basic method, which is to talk about comics using comics.

It worked in UC, partly because to illustrate the idea of comics he used comics. Talking about time in comics, for instance, he showed (pp. 100-102) some rather amusing panels of a couple of slackers talking. By contrast, a typical illustration in RC is a sketch of someone involved in comics or the Internet, or an iconic restatement of the text-- the comics industry, for instance, is drawn (over and over again) as a big snakelike dollar sign.

It's not that much different, then, from a typical essay in Slate, except that instead of a new illo for every three paragraphs, you get a couple per sentence. The effect is frankly a bit tiring. (And despite his theory about cartooned figures, too much abstraction destroys reader identification. To talk about art in UC, McCloud invented a handful of artists; they were specific enough to be memorable-- they worked as characters. To talk about art in RC, he uses a generic Artist Icon in visor and black vest, about as easy to identify with as a Ped Crossing sign.)

More interesting is to turn to McCloud's actual experiments. One plays with

both form and interactivity:

Choose Your Own Carl

is an interlocking crossword-puzzle of panels dealing with Carl, a hapless walk-on

from UC; if the multiple paths weren't enough, the content of each panel is

suggested by McCloud's readers. (He used my ideas twice! Whee!)

More interesting is to turn to McCloud's actual experiments. One plays with

both form and interactivity:

Choose Your Own Carl

is an interlocking crossword-puzzle of panels dealing with Carl, a hapless walk-on

from UC; if the multiple paths weren't enough, the content of each panel is

suggested by McCloud's readers. (He used my ideas twice! Whee!)

This is all just for fun, but it's quietly revolutionary, effectively making McCloud's point that comics on-line shouldn't just attempt to shoehorn paper panels onto the monitor, but should do things that were simply not possible on paper.

A more serious work is My Obsession with Chess, one of the first demonstrations of McCloud's ideas that online comics should spread out into huge vistas, rather than being divided into panels or pages. Here, it allows him to play up the resemblance of cartoon panels to chess squares; and it's a good dollop of autobiography, too.

He continues his ruminations on comics in comics in an on-line column. If anything these work better than RC, but they tend to give me the same sense of wondering why a 500-word essay (i.e., shorter than this review) has been so laboriously illustrated.

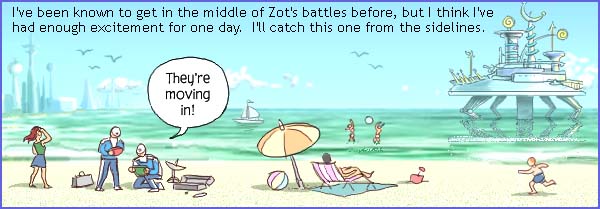

Perhaps the documentary form is inherently difficult; what about narrative? Check out McCloud's Zot! Online-- where McCloud's ideas about computer comics finally come to life.

I preferred the black & white bits of the old Zot!; but one reason is that the colored books were colored so awfully. The online Zot! is really pretty, and another point is made-- how much American comics have missed soft-focus and subtle colors.

You move through McCloud's comics by scrolling, and he's already learned how to use this to impart a sense of time. I particularly liked a huge panel in episode 3, representing an explosion in the air and the subsequent long, long fall. You couldn't do that on paper, where it'd just be a bunch of pictures of people in a void. A similar technique is used in episode 2 to dramatize a character's extreme reluctance to speak.

The backstory on Dekko, also in episode 2, is worth the whole trip... the simple narrative explodes into an array of graphical experimentation, reinforcing the notion that we're dealing with someone who's disturbed yet brilliant. (No, not McCloud, silly-- Dekko.)

This just in-- McCloud's run of Zot! is done. It's a must-read to see the possibilities of on-line comics; as a story, it unfortunately demonstrates once again the bankruptcy of the superhero genre. There's a real idea there (would it be better to have an eternal robotic body?), but there's simply no room to explore it after cramming in the boilerplate hero/villain rigmarole. Blade Runner explores the concept further in five minutes than all sixteen episodes of Zot! do.

| Tristan Farnon: Leisuretown | |

First, form: the comics look like photographs of big rubber animals in actual locations. I have no idea how he does them, really, except that they involve a good photo editor and insane patience... not only must the technique take longer than drawing would, but some of these comics are over a hundred pages long. Whatever it is exactly, it works. The comics have a look unlike any other; and the cheesy-looking toys set up some expectations about content which Farnon then proceeds cheerily to demolish.

Content: the title could just as well have been Misanthropy Theater. They mostly focus on slackers in dead-end jobs, their general sense of being smarter than everyone else tempered by a realization that this is getting them absolutely nowhere. The latest installment, "QA Confidential", starts out discussing temp jobs, and moves on to the dilemma of QA (no one, but no one, wants to see the bug you've found). Much of this is blisteringly satirical (and even insightful), and you won't want to miss the hilarious media parodies, such as the Tetris-like game called Shit Keeps Falling. And then, if you can believe it, the story turns dark.

Leisuretown isn't for everyone; it's intended for people who find a comic called "American Masturbator" hilarious rather than just evil. (If "intended" is the right word; Farnon isn't exactly market-testing to reach the widest audience, here.) It's not exactly funny; it's entertaining in the way the best rants are. Anyone can rant; some have the ability to rant well. My best example (the Meaningless Drivel Home Game) has disappeared from the web (except for a remnant); but you could try Jamie Zawinski, or my pal who does Not My Desk, or Justin Rye's SF/linguistics pages. It can be baffling why these folks are quite as worked up as they are; but they don't have the humorless unreadability of the true crank (say, Edo Nyland on how all languages derive from Basque... or Dave Sim on women).

This just in: Farnon is now a little less mysterious: TCJ has published an interview with him.