|

| ||||||

Introduction

— People

— Family

— Terms

— Sources

Phonology

— Consonants

— Vowels

— Phonotactics

— Stress

Orthography

Morphology

— Nouns

— Pronouns

— Numbers

— Verbs

— Derivational

Syntax

— Sentence order

— NP order

— Negatives

— Questions

— Copulas

— Conjunctions

— Possession

— Locatives

— Giving and speaking

— Serial verbs

— Causatives

— Purpose

— Relative clauses

— Aspect contrasts

— Comparatives

Semantic fields

— Polite formulas

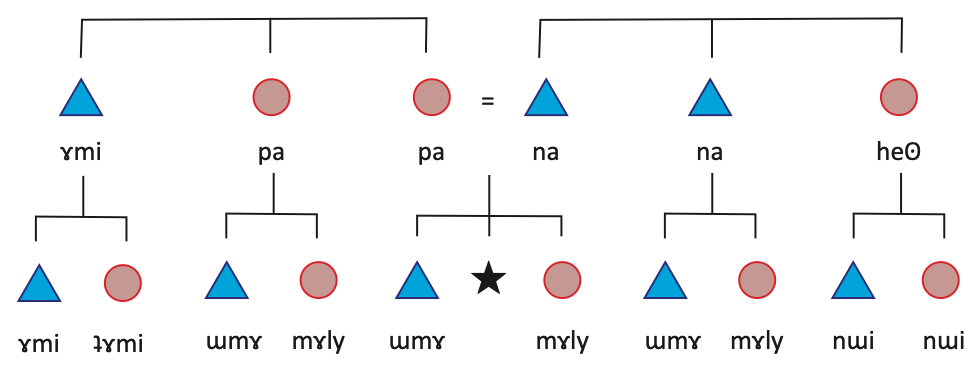

— Kinship terms

— Names

Samples —

Gods and humans –

Recording

© 2021 by Mark Rosenfelder

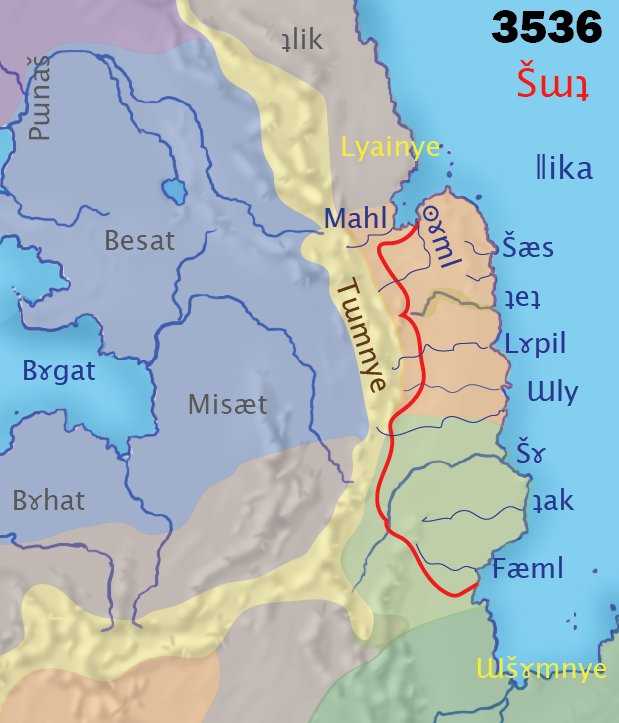

Šɯʇ adopted agriculture from the Bhöɣetans around 1300 Z.E.; we don’t know if the Šɯʇ went to the Bhöɣeta, or if Bhöɣetan settlers arrived. (There is no trace of Bhöɣetan languages in the area.) Chiefdoms appeared in each of the twenty river valleys (ǁɤ) that run through the desert.

Right: Šɯʇ and its major rivers. The orange area is desert; the light green, subtropical. The map is labeled in Šɯk. ǁika is the name of the ocean.

The most populous valley, Šɤ, conquered the remaining valleys by 3400. As it was ruled by a queen, Nyaʇa, and she had only one daugher, ǁika, she proclaimed that only queens could rule Šɯʇ. As a result the queendom was matriarchal, a practice soon adopted by the chiefdoms; families outside the elite remained male-dominated.

In the 3540s the Šɯʇ were decimated by Ereláean diseases; this made it easy for Verdurians to begin settling the river valleys. In 3549 queen ʘisa attempted to repress ʇak, the valley to the south, which had accepted Verdurian sovereignty. The Verdurians took the opportunity to conquer the Šɤ valley, depose ʘisa, and assert their authority over all of Šɯʇ. In 3551 the region was organized as the colony of Šočya.

Some of the more interesting features of Šɯk:

The family can be divided into north and south— the languages of Črek and Šɯʇ, separated by an icëlan forest. Črek (ʇlik) is steppeland, and its people were hunter-gatherers and then pastoralists; they rarely interacted with the southern group and were not part of the Šɯʇ queendom.

Within South Šɯʇian, each valley developed its own culture and language— as the Šɯʇ say, ǁɤ nya kah ket: “Every valley its own language.” Almean linguists have taken them at their word, cataloguing twenty different South Šɯʇian languages. This is undoubtedly exaggerated: e.g. it’s clear that the varieties spoken in the adjacent Šɤ and ʇak valleys, though clearly distinguished, are mutually intelligible.

In general people could understand the languages two or three valleys over, but not farther. That is, there is a clear north-south geographical continuum, with no obvious discontinuities, except for the three northernmost languages (ʘɤml, Mahl, and a minor river in between). There is no consensus on how many languages there “really are” nor on where the divisions should be put.

I will use Šɯʇ only for the entire region (i.e. Šočya). In Šɯk, if desired, it was possible to distinguish ʇšɤ ‘inhabitant of the Šɤ valley’ from ʇpily ‘inhabitant of Šɯʇ’.

When the Verdurians arrived they made laymen’s approximations to Šɯk words— e.g. Šɯʇ > Šoč > Šočia > Šočya; Šɤ > Šö; ʘisa > Bisa. Šɯk was sometimes Šuc and sometimes Šočë. These became conventional, but I will avoid Verdurianisms here.

This is post-contact (so there are words for Verdurian things), but does not reflect the thorough Verdurianization already underway at that time, which would make the language almost unrecognizable by the time Angen pubished her grammar in 3646.

The corpus of classical Šɯk is disappointing. Scholars collected songs, folk tales, and myths, but these amount to a few volumes, and no one thought about recording ordinary conversation (though we do have a few phonographic recordings made in the 3590s). By the time scholars paid more attention to everyday language, Šɯk had greatly changed, and no more precolonial speakers existed.

As a result we cannot answer all the questions we might have about Šɯk, and aspects of the grammar are still debated.

Šɯk is notable for having three click consonants. These are formed by articulating a stop and creating suction, then releasing it suddenly.

labial dental post-alv velar stops p b t d k g clicks ʘ ǁ ʇ fricatives f s š h nasals m n ny liquids l ly

h is pronounced /h/ by women and the elite, and as /x/ by everyone else.

Some of the other Šɯtian languages, especially in the north, have a wider range of clicks.

There are six vowels; note that the back vowels are unrounded— there are no phonemes /u o/. The Verdurians often hear ɯ ɤ as ü ö; this will seem strange if you’re thinking of the rounding, but makes more sense if you think of them as “not /u o/ for some reason”. The Kebreni represent ɯ as their y y.

front back high i ɯ mid e ɤ low æ a

On the allophonic level, after a labial consonant (including ʘ), the back vowels are somewhat rounded. Thus pɯt mɤ are pronouced [put mo]. Similarly, front vowels are rounded after ny ly, so nyik lyeh are pronounced [ɲük λöh].

For the syllabic consonants, cf. ʇ-pily, ʇ-šɤ, kɯs-ǁ, l-hɤn, ǁit-l, kak-s. This can happen only if the consonant is followed or preceded by another consonant: ǁika is ǁi-ka, not ǁ-i-ka. Note that nɯš-s is pronounced [nɯʃ:]. A very few words have no vowels, e.g. ʘǁ, sʘ.

Earthly click languages normally restrict the clicks to the syllable onset, but Šɯk does not.

Voicing is lost word-finally. Fricatives are voiced in medial position— e.g. ifa is pronounced [iva].

Multiple vowels should each get their own syllable— e.g. hɤi is [hɤ i] or even [hɤ ʔi], not [hɤj].

The motivating principle for the orthography— not unknown in terrestrial linguistics— is “make use of what’s already on the typewriter.”

labial dental post-alv velar stops p p t t c k b b d d g g clicks w ʘ ® ǁ ç ʇ fricatives f f s s ß š h h nasals m m n n ny ny liquids l l ly ly

That is, the Verdurians write ɯ ɤ as u o— though they usually borrow them as ü ö. ä for æ (Verdurian ä) is another case of using a convenient, vaguely related letter.

front back high i i u ɯ mid e e o ɤ low ä æ a a

Scholars sometimes use the Almean phonetic alphabet, but Šɯk speakers have stuck with the system above.

If you use the Verdurian font,

On the Mac,

š k u o æ ʘ ǁ ʇ lye nye ß c u o ä w ç ® lë në

But add some modifiers, and you’ll see that the clitic applies to the end of the NP:

pa sɤl > pa sɤlnye ‘the good mothers’As the clitics end an NP, they can stack. ɯsak ʘilyat ‘the queen’s healer’ is straightforward, but note

pa sɤl > pa sɤlat ‘of the good mother’

pa sɤl ʘe > pa sɤl ʘeny ‘those good mothers’

meç usac wily-at-at-nëIt may be hard to wrap your head around this, but it’s a simple application of the NP rule. It may be easier to understand if we add brackets and colors:

meʇ ɯsak ʘily-at-at-nye

son healer queen-gen-gen-pl

the sons of the queen’s healer

[meʇ ɯsak [ʘily-at ]-at ] -nye

son healer queen-gen -gen -pl

the sons of the queen’s healer

s pl 1 nim nimnye 2 gɤm gɤmnye

naps my or our houseThese are not clitics, but inflections, so you say e.g. napsnye ‘my houses’, naps siny ‘my beautiful house’.

napl your house

napnɤ his/her house

(We’ll meet these same affixes in the verbal morphology, but note that the ‘you’ marker works differently for verbs.)

The first column is used with a noun: nily baly ‘this girl’, nily ʘe ‘that girl’.

adj NP anim NP inan this baly ɯbaly bah that ʘe ɯpe ʘeh

The other forms take the place of an entire NP. The ɯ- form is used for animates, the -h form for inanimates. These can also be used as 3rd person pronouns.

none siThe quantifiers are adjectives, following the noun: nyeš si ‘no person’, he nya ‘all temples’.

some hiʘɤ

other aly

many lyɤ

all nya

To form NPs, these are combined with an appropriate generic noun— nyeš ‘person’, tat ‘thing’, mat ‘day’, mɯs ‘place’ are the most common, but something more specific can be used.

There is also nyɤʘ for ‘why’.

The numbers 5 and up are largely borrowed from Bhöɣetan. Lyeh, now ‘10’, is related to lyɤ ‘many’ and probably once meant only ‘more than four’.

n n+10 1/n Verd 1 pæ lyeh se 2 hi lɯka mai 3 ʘɤ lɯka se eke 4 ely lyeh elybæ ʘelyat pal 5 nyar lyeh nyarbæ ʘnyarat pan 6 nyaši lyeh nyašibæ ʘnyašit ses 7 nyalɯ taha kai ʘnyalɯt ep 8 nyaʇap teha ʘnyaʇapat šɤk 9 mida ʘmidet nef 10 lyeh ʘlyihat dek

100 is dašaʇ, 324 is tenaʇ.

Multiplication is implied by concatenation. This allows multiples of 10 or 18 to be used:

Addition is indicated with the clitic -bæ:

lyeh hi 20 lyeh nyaši 60 teha hi 36 teha nyar 90 dašaʇ hi 200 tenaʇ ʘɤ 972

Merchants in Šɯʇ often simply used a Bhöɣetan language for counting and arithmetic (indeed, they were often Bhöɣetans themselves). Unsurprisingly, Verdurian numeration was adopted quickly; the last column of the table shows the borrowed numbers. (Native 1 2 3 were kept.)

lyeh elybæ 10 4-and 14 lyeh nyaši ʘɤbæ 10 6 3-and 63 dašaʇ hi lyeh nyašibæ 100 2 10 6-and 260 teha hi nyalɯbæ 18 2 7-and 43

Numbers follow the noun, usually with no plural: nily ʘɤ ‘three girls’.

Thus:

-s I/we e- you -n he/she/it/they

When there’s a final consonant, as with kak, -s becomes syllabic.

kɯs I go, we go ekɯ you go kɯn he/she goes, they go mes I am, we are eme you are men he/she is, they are kaks I speak ekak you speak kan he speaks

The 3rd person -n usually eats the final consonant. But there are exceptions, marked in the lexicon: e.g. kap ‘hide’ > kam ‘he/she hides’.

Here are all the combinations for hɤl ‘see:

s- me/us l- you ʘ- him/her/it/them

Object marking is not used in the following cases:

Subject 1 2 3 Object (none) hɤls ehɤl hɤn 1 sehɤl shɤn 2 lhɤls lhɤn 3 ʘhɤls ʘehɤl ʘhɤn

As perception and belief are immediate, verbs expressing these can be used in the present: hɤls = ‘I see’ or ‘I saw’.

There are three clitics which express various aspects and modalities. Only one can be used at a time.

The idea is that the action starts and stops, as opposed to the imperfective which describes a prolonged or uncompleted action.

kɯkɯs I went often, I go on and on hɤhɤs I watched often, I watched and watched kakas I spoke often, I spoke a lot ʇɤʇɤs I coughed often, I had coughing fits

It can be combined with the irrealis (ha-ekakas ‘you should speak often’) or intentive (ge-kakas ‘I will speak a lot’).

Thus kɯn ‘he went’, but mɯkɯn ‘he came’, i.e. ‘he went towards me’.

The combination mɯ + e- > mɤ; thus ekɯ ‘you went’ > mɤkɯ ‘you came’.

The ventive often becomes a simple benefactive: e.g. a queen may boast mɯlin he ‘they built the temple for me’. You can also use the ventive with reference to your household or institution, so long as you are closely associated with it. E.g. a member of the queen’s court could also say mɯlin he, though the benefit is understood to be for the queen.

If ǁ is applied after the subject affix -s, the final consonant of the root disappears: thus kasǁ ‘I didn’t speak’.

kɯsǁ I didn’t go ekɯǁ you didn’t go kɯnǁ he didn’t go me-kɯsǁ I wasn’t going, I’m not going ha-kɯsǁ I shouldn’t go kɯkɯsǁ I wasn’t going a lot mɯkɯnǁ he didn’t come

If ba- is used, omit the 3rd person -n if any. Ba + e- > bæ-.

First, it’s a reflexive: hešs ‘I washed it’ > bahešs ‘I washed myself’.

Second, it expresses an agentless action. This is similar to a passive, but it’s generally used when there is no apparent agent at all. Compare ssan ‘he healed me’ with bassak ‘I got better’. Baniǁ fɤt ‘the door opened’ is appropriate when the door opens by itself, but not when an indefinite subject is meant.

This meaning is often lexicalized as a change in valence, but note that the person experiencing the action continues to be expressed as an object, not a subject. Thus eǁan ‘he killed you’ > bæǁat ‘you were killed’.

Finally, with verbs of perception or belief, the middle expresses a change of state. Thus hɤls ‘I saw it’ > bahɤls ‘I came to see it, I (just then) noticed it.’

It’s negated in two ways. The normal negative ǁ is used to prohibit an action: kɯǁ! ‘don’t go!’ By extension, ǁ alone has the meaning ‘Don’t!’

The verb ɤʇ means ‘stop’, but can be prefixed to an imperative with the meaning ‘stop that’. Thus ɤʇ-kɯ! ‘stop going!’ This can be abbreviated ɤʇ! ‘stop!’

The other verb prefixes can be used, sometimes with slightly changed meanings:

ɯ- doer ɯsak healer -(i)h nominalizer (fronts vowel) kak speak > kah language ʘ- concrete object (plus genitive) nye evil > ʘnyit monster -k language Bedur Verduria > beduk Verdurian ʇ- member nam palace > ʇnam courtier -m augmentative nap house > nam palace -l adjectivizer (syllabic after a consonant) ǁit heart > ǁitl vigorous -ly feminine hik husband > hily wife -a verbalizer fih work > fiha work

‰an wnyit utul.The fact that verb affixes are in the order O-V-S (mostly; subject e- is an exception) makes linguists wonder if the syntactic order was once OVS. But there is no direct evidence of this.

ǁanʘnyit ɯtɯl .

kill.3 monster warrior

The warrior killed the monster.

Mecan wily çe.

Mekanʘily ʇe .

irr-see.3 queen priest

The priest should speak to the queen.

If the object is not stated, and it’s animate, it’s marked on the verb with ʘ-:

W®an utul.We do see VSO sentences, which show object agreement. They are thus a form of topicalization.

ʘ ǁan ɯtɯl.

3-kill.3 warrior

The warrior killed it.

W®an utul wnyit.1st and 2nd person arguments are expressed using verb affixes. Personal pronouns are rare.

ʘ ǁanɯtɯl ʘnyit .

3-kill.3 warrior monster

The monster, the warrior killed it.

Mecacs wily.Another form of topicalization is to front an argument, replacing it with ɯpe/ʘeh ‘that one (animate/inanimate)’.

Me-kaks ʘily.

irr-see-1 queen

I should speak to the queen.

Mewcacs.

Me-ʘ kaks .

irr-3-see-1

I should speak to her.

Utul, çan wnyit upe.

Ɯtɯl , ǁan ʘnyitɯpe .

warrior / kill.3 monster that.one

The warrior, he killed the monster.

Wnyit, çan upe utul.

ʘnyit , ǁanɯpe ɯtɯl.

monster / kill.3 that.one warrior

The monster, the warrior killed it.

Modifiers relate to the preceding noun. Compare:

nily a girl nily siny a beautiful girl nily baly this girl nily siny baly this beautiful girl nilynye girls nily balynye these girls nily nyar five girls nily siny nyar balynye these five beautiful girls nily naǁatnye the girls of the city nily naǁše a girl from the city nily naǁšenye girls from the city nily naǁnyeše a girl from the cities nily ǁanl ɯtɯl the girl who killed the monster

nily siny nyar na®atThere are no articles.

nily sinynyar naǁat

girl beautiful five city-gen

the five beautiful girls from the citynily sinynë na® nyarat

nily sinynyenaǁ nyarat

girl beautiful city five-gen

the beautiful girls from the five cities

‰an® wnyit utul.If you want to negate a particular element, use the quantifier si ‘none’. The ǁ suffix is optional in this construction.

ǁanǁ ʘnyit ɯtɯl.

kill.3-not monster warrior

The warrior didn’t kill the monster.

‰an(®) wnyit si utul.

ǁan(ǁ) ʘnyitsi ɯtɯl.

kill.3-(not) monster none warrior

The warrior didn’t kill any monster.

‰an wnyit utul mew?The simplest answer is ʘeh, literally ‘That.’ Colloquially, just ʘ will do. You can also repeat the verb, though be careful when pronominal affixes appear as they must be corrected:

ǁan ʘnyit ɯtɯlmeʘ ?

kill.3 monster warrior Q

Did the warrior kill the monster?

—Me-wecacs mew?The negative response is meǁ ‘no’ (literally ‘it is not’). Colloquially you can just utter ǁ.

—Me-ʘekaks meʘ?

irr-3-see-1 Q

Should I speak to her?—Mi-wecac.

—Mi-ʘekak .

irr-3-2-see

Yes, you should speak to her.

You can question a negative statement the same way:

‰an® wnyit utul mew?Here ʘeh affirms the negative: “Right, he didn’t kill it.” To affirm the positive— “he did kill it”— you say aly, literally ‘the other’. If that is confusing, just use the verb (ʘǁan ‘he killed it’, ʘǁanǁ ‘he didn’t kill it’).

ǁanǁ ʘnyit ɯtɯlmeʘ ?

kill.3-not monster warrior Q

Didn’t the warrior kill the monster?

You can also answer questions with edaš ‘you know’. This is the response when the answer is obvious, or you suspect the speaker is playing games (they’re speaking rhetorically or evasively).

‰at wnyit ow?When pronominal affixes are involved, there will be only one argument, but the affixes will make the meaning clear.

ǁat ʘnyitɤʘ ?

kill monster who

Who killed the monster?

‰an ow utul.

ǁanɤʘ ɯtɯl.

kill.3 who warrior

What did the warrior kill?

‰ats ow?The interrogative can take the locative and genitive clitics:

ǁatsɤʘ ?

kill-1 who

What did I kill?

S®at ow?

Sǁatɤʘ ?

1-kill who

What killed me?

Mi-ekɯ ownyät?To query a time, use an expression like mat ɤʘ ‘what day’:

Mi-ekɯɤʘnyæt ?

imperf-2-go who-allat

Where are you going?

Men nap owat bah?

Men napɤʘat bah?

be-3s house who-gen this-inan

Whose house is this?

Moku mat ow?There is a separate interrogative nyɤʘ for ‘why’:

Mɤkɯmat ɤʘ ?

vent-2-go day who

When did you arrive?

Nyow men ßel ßom?

Nyɤʘ men šel šɤm?

why be-3 sky blue

Why is the sky blue?

Men unyeh çbedurnë.This statement can be used of a present or past state. The imperfective (me-me) is used for a temporary state. Compare:

Men ɯnyeh ʇbedɯrnye.

be-3 villain Verdurian-pl

Verdurians are villains.

Me-men Usiny ßap.However, it’s more common to simply treat a one-word predicate as a verb. This construction always expresses the current condition without asserting that it is permanent.

Me-men Ɯsiny šap.

be-be-3 Ɯsiny drunk

Ɯsiny is currently drunk.

Men Usiny ßap.

Men Ɯsiny šap.

be-3 Ɯsiny drunk

Ɯsiny is a drunkard.

Nyen çbedurnë.Note that denominals like ɯnyeh (‘villain’, literally ‘evil one’) are replaced by their roots in this construction.

Nyen ʇbedɯrnye.

evil-3 Verdurian-pl

Verdurians are evil.

Ían Usiny.

Šam Ɯsiny.

drunk.3 Ɯsiny

Ɯsiny is drunk.

Again, the clitic attaches to an entire NP.

nily nyaßl ßim sinybäGrammatically, the NP+clitic modifies the first name, and thus is not reflected on the verb. That is, only the first conjoint triggers verbal agreement:

nily nyašl šim sinybæ

girl brave boy beautiful-com

the brave girl and the beautiful boy

Me-gewen nas nimbä.If you have more than two conjoints, add -bæ only to the last: ʘily nam nyešbæ ‘the queen and the court and the people’.

Me-geʘen nas nimbæ.

impf-argue.3 father-1 I-com

My father and I were arguing.

Me-gewems nim nasbä.

Me-geʘems nim nasbæ.

impf-argue-1 I father-1-com

I and my father were arguing.

The clitic can’t be used with adjectives or verbs. But in these cases concatenation can be used:

nily nyaßl sinySentences are conjoined with ifa:

nily nyašl siny

girl brave beautiful

the brave beautiful girl

Íin nen wily.

Šin nen ʘily.

eat.3 sleep-3 queen

The queen ate and slept.

Nen wily, ifa mucun wnyitnë.which is also used (more rarely) with other constitutents

Nen ʘily,ifa mɯkɯn ʘnyitnye.

sleep-3 queen / and vent-go monster-pl

The queen slept, and the monsters came.

nily nyaßl ifa ßim sinyOther conjunctions are far simpler, being particles that work the same with all constituents. E.g. han ‘or’:

nily nyašlifa šim siny

girl brave and boy beautiful

the brave girl and the beautiful boy

matßemat han matolat

matšemathan matɤlat

summer or winter

summer or winter

Íin wily, han nen.

Šin ʘily,han nen.

eat.3 queen / or sleep-3

The queen ate, or she slept.

çɯny uçetAgain, the clitic –(a)t attaches to the end of the NP, which can produce a stack of clitics at the end of a complex phrase:

ʇɯnyɯʇet

pot potter-gen

the pot of the potter

hily uçet

hilyɯʇet

wife potter-gen

the wife of the potter

uß lyainyit

ɯšlyainyit

forest icëlan-pl-gen

the forest of the icëlani

Cus nap nily sinynyitnyät.Genitives are often lexicalized, with an initial ʘ deriving from ʘe ‘that’— e.g. ʘe neʇat ‘that of the bee’ > ʘneʇat ‘honey’; ʘe gɤlyat ‘that of the penis’ > ʘgɤlyat ‘semen’. This is also the regular way to form fractions, e.g. ʘnyašit ‘that of six > one sixth’.

Kɯs nap nily sinynyitnyæt .

go-1 house girl-beautiful-pl-gen-allat

We’re going to the house of the beautiful girls

Existentials are expressed with the verb kɤ (not me). Note that locatives are placed just after the verb, and the subject at the end.

Con na®il saßaly siny.

Kɤn naǁil sašaly siny.

exist-3 city-loc prostitute beautiful

There is a beautiful prostitute in the city.

Possession uses the same expression, with a genitive in second position:

Con nilyat nap siny.1st person possession uses the ventive:

Kɤnnilyat nap siny.

be-3 girl-gen house beautiful

The girl has a beautiful house.

Mucon nap siny2nd person possession uses the prefix l-; that is, ‘you’ is treated as the object.

Mɯ kɤn nap siny

vent-be-3 house beautiful

I have a beautiful house. (Lit. there exists for me…)

Lcon hily siny.

L kɤn hily siny.

vent-be-3 wife beautiful

You have a beautiful wife. (Lit. there exists you…)

Ulyos na®il.Like the plural and genitive, these are clitics, not affixes: naǁ sinyil ‘in the beautiful city’, naǁ siny mæše ‘from the beautiful big city’.

Ɯlyɤsnaǁil .

reside-1 city-loc

I live in the city.

Cos na®nyät.

Kɯsnaǁnyæt .

go-1 city-allat

I went to the city.

Cos na®ße.

Kɯsnaǁše .

go-1 city-abl

I left the city (literally, went from it).

For more precision, you can use expressions like

guhil dacatIn the above sentences the locative is an argument. It can also be used as an NP modifier:

gɯhil dakat

bottom-loc tree-gen

at the bottom of the tree

na® moiLocatives are also used for time:

naǁmɤi

city water-loc

a city on the river

Pon hicnyät nam wily.When the recipient is not explicitly given, however, it is represented by the object prefixes on the verb:

Pɤnhiknyæt nam ʘily.

give.3 husband-allat palace queen

The queen gave her husband a palace.

Spon nam wily.A 1st person object can also be expressed with the ventive: Mɯpɤn nam ʘily.

S pɤn nam ʘily.

1-give.3 palace queen

The queen gave me a palace.

Wpon nam wily.

ʘ pɤn nam ʘily.

3-give.3 palace queen

The queen gave him a palace.

The same is true of verbs of speaking:

Lcan wnyit.

L kan ʘnyit.

2-speak.3 monster.

The monster spoke to you.

Menon däfa nily.An object can be included, but it triggers verbal agreement on the main verb; this can be seen as a form of Raising.

Menɤndæfa nily.

impf-want.3 dance girl

The girl wants to dance.

Menon ßif whanet nily.If the subordinate verb is intransitive, its subject can be expressed, and also triggers object agreement on the main verb:

Menɤnšif ʘhanet nily.

impf-want.3 eat peach girl

The girl wants to eat a peach.

Smenon cac nily.

S menɤnkak nily.

1-impf-want.3 speak girl

The girl wants to speak to me.

Meße®n ku çe nily.If you want to express both subject and object of the subordinated verb, there are two methods. First, the subordinate subject can be expressed as an allative:

Mešeǁnkɯ ʇe nily.

impf-await.3 go priest girl

The girl hopes the priest will go.

Lmeße®n ku nily.

L mešeǁn kɯ nily.

2-impf-await.3 go girl

The girl hopes you will go.

Ren ßif whanet çenyät nily.Second, you can state the subordinated sentence separately, either fronted or backed, and refer to it with ʘeh ‘that’.

ǁenšif ʘhanet ʇenyæt nily.

order-3 eat peach priest-allat girl

The girl ordered the priest to eat a peach.

‰en weh nily, ha-ßin whanet çe.Note that the subordinated sentence is inflected like an independent sentence. In this case it’s irrealis, so that we’re reporting the order without stating that it was carried out. If the priest did eat the peach, you use the realis.

ǁen ʘeh nily,ha-šin ʘhanet ʇe .

order-3 that.one girl / irr-eat.3 peach priest

The girl ordered the priest to eat a peach.

One is lexical, and is of course limited to what the lexicon supplies. E.g. hol is ‘see’, naʘ is ‘cause to see’, i.e. ‘show’. Also note the pattern exemplified by ǁat ‘kill’, which in the middle voice means ‘die’.

Second, we can use a subordinated verb, often with the main verb gai ‘cause’:

Gain nily, ßin whanet çe.Third, the causer can replace the subject, which is demoted to an allative:

Gain nily,šin ʘhanet ʇe .

cause-3 girl / eat peach priest

The girl made the priest eat a peach.

Íin whanet çenyät nily.If the causee isn’t directly expressed, and the normal object is inanimate (like the peach), the causee triggers verbal agreement:

Šin ʘhanetʇenyæt nily.

eat.3 peach priest-allat girl

The girl made the priest eat a peach.

Wßin whanet nily.

ʘ šin ʘhanet nily.

3-eat.3 peach girl

The girl made him eat a peach.

Popan utul, mutil niwa wnyit.The interrogative nyɤʘ X ‘why X’ can also be used as an object:

Pɤpan ɯtɯl,mɯtil niʘa ʘnyit .

walk-3 warrior / mind-in touch monster

The warrior walked, intending to find the monster.

Nɯßs nyow mocu.

Nɯšsnyɤʘ mɤkɯ .

seek-1 why vent-2-go

I want to know why you came.

Min wilynyenyät çe.The participle can optionally take inflections: lmikl ‘sacrificing to you’, hamikl ‘possibly sacrificing’, miklǁ ‘not sacrificing’, etc.

Min ʘilynyenyæt ʇe.

sacrifice god-pl-allat priest

The priest sacrificed to the gods.

> çe micl wilynyenyät

> ʇe mikl ʘilynyenyæt

priest sacrifice-adj god-pl-allat

the priest who sacrificed to the gods

If it’s the object that’s relativized, it should be represented by an object prefix on the participle.

‰an wnyit utul.

ǁan ʘnyit ɯtɯl.

kill.3 monster warrior

The warrior killed the monster.

> wnyit wçanl utul.

> ʘnyitʘ ǁanl ɯtɯl.

monster 3-kill.3 warrior

the monster that the warrior killed

Me-nen wnyit, whon utul.ha + me (irrealis + imperfective) expresses a conditional. The presupposition is that the condition is untrue or unknown.

Me -nen ʘnyit, ʘhɤn ɯtɯl.

impf-sleep-3 monster / 3-see-3 warrior

The monster was sleeping when the warrior saw it.

Ha-babeß ®o, me-babeß mupily.ha + ge (irrealis + intentive) expresses a conditional vow or warning: “If this happens, may this happen!” In this construction only, ge- may be used for non-1st-person subjects.

Ha -babeš ǁɤ,me -babeš mɯpily.

irr-mid-lose valley / impf-mid-lose queendom

If the valley is lost, the country is lost.

Ha-bassac gupl, gi-emik poc.

Ha -bassak gɯpl,gi -emik pɤk.

irr-mid-heal dog-2 / intent-2-sacrifice flauk

If your dog gets better, you must sacrifice a flauk.

Men Laß siny se Filai.For “less” use kai in place of se.

Men Laš sinyse Filai.

be-3 Laš beautiful more Fila-loc

Laš is more beautiful than Fila.

Without a comparison NP, the expression is superlative:

Men Laß siny se.

Men Laš sinyse .

be-3 Laš beautiful more

Laš is the most beautiful.

With nobles, a lesser person instead says Baʘɯts ‘I abase myself’. You can add a title, but the Šɯʇ norm is for inferiors to say as little as possible, not to be florid.

Lower-class people are known, or notorious, for the greeting ssǁ— the [s] is loud and prolonged. A relatively mild put-down for the masses is ʇsǁ, the people who say ssǁ.

On parting, you say tan ʘinye, literally “The gods call”— the idea being that only a summons from the gods is grounds for ending a conversation. The response is Tan kɯbæ “They summon so go!” (a rare use of the conjunctive clitic with verbs).

If you receive something, you say Enyɤl ‘you are kind’; the response is Ekak ‘you say it’, which in general is used for noncomittal replies (“is that so”).

If you’re mildly sorry about something, you say Mæm dɯǁs ‘great is my sin’; the response is kɤǁ ‘it doesn’t exist’.

You would add honorifics before a superior’s name, and in elite contexts, to an equal’s or even a lofty inferior’s: ʘily Laš ‘Queen Laš’, An Laš ‘Lady Laš’, hɯm Laš ‘elder Laš’, umɤ Laš ‘older brother Laš’. An all-purpose honorific was sɤl ‘good’.

Relatives of your spouse are formed with the appropriate genitive, e.g. pa hilyat ‘mother of-wife = mother-in-law’. If it’s clear (e.g. on second reference, or addressing the person), you can just say hilyat, or hikat if you’re female.

Names are unisex, at least from the time of queen Nyaʇa who established female dominance in the nobility.

One-syllable names are preferred, but two-word N+A phrases are not uncommon, e.g. meʇsiny ‘beautiful boy’, filašɤm ‘blue flower’, keǁip ‘fast sword’.

Names can also be inflected verbs:

In such names final 3s -n is optional: the last name could also be kakak. Queen Nyaʇa’s name means ‘it thunders’.

šeǁs we waited snan he/she (probably a god) showed to us gemih I will sacrifice kakan he/she talks a lot

The text explains, but also simplifies, the two classes of spriritual beings— gods (m. ʘi, f. ʘily) and spirits or godlings (fæm ‘great soul’). The gods were powerful; there was at least one per valley, with the gods of the Šɤ valley (ʘai Ɯʇa and An ǁikam) above them all. The godlings had less power, but were far more approachable. There was a tendency, not universal, for the elite to worship gods and the rabble to follow spirits, which may mean that they are really from different religious systems entirely.

Mat saii, con no Wai Uça.

Mat saii, kɤn nɤ ʘai Ɯʇa.

day early-loc / exist-3 only lord shaper

One day, there was only ʘai Ɯʇa.

Con® nëcnë si.

Kɤnǁ nyeknye si.

exist-3-not land-pl

There was no world, no spirits.

Çan An ‰icam hilyno wgolyatnoße.

ʇan An ǁikam hilynɤ ʘgɤlyatnɤše.

create-3 lady ocean semen-3-abl / wife-3

He created An ǁikam from his semen as his wife.

Wmon çiçi lyo, ifa mon alynë çiçiny: men fämnë.

ʘmɤn ʇiʇi lyɤ, ifa mɤn alynye ʇiʇiny: men fæmnye.

3-bear-3 child many-pl / and 3-bear other-pl child / be-3 spirit-pl

She bore him many children, and their children had other children, who were the spirits.

Con® upit nap, hoi gain wai Uça Weš Wai Nëh, ifa çan nëc mobä.

Kɤnǁ ɯpit nap, hɤi gain ʘai Ɯʇa ʘeš ʘai Nyeh, ifa ʇan nyek mɤbæ.

exist-3-not that.one-gen house / therefore cause-3 lord shaper fear lord chaos / and create-3 land water-and

There was no room for them, so ʘai Ɯʇa frightened Chaos and made land and water.

Ulyon wi fämnëbäi, ifa wtun Wai Nëh buha nyai.

Ɯlyɤn ʘi fæmnyebæi, ifa ʘtɯn ʘai Nyeh bɯha nyai.

reside-3 god spirit-pl-and land-loc / and 3-fight-3 lord chaos night every-loc

The gods and the spirits lived in the land, but Chaos fought them every night.

Oçlil, çen Wai Nëh An ‰icam, hoi con saßa.

ɤʇlil, ʇen ʘai Nyeh An ǁikam, hɤi kɤn saša.

end-loc / destroy-3 lord chaos lady ocean / therefore exist-3 peace

Finally An ǁikam destroyed Chaos, so that there was peace.

Con wi fämnëbä, ifa nëßnë si.

Kɤn ʘi fæmnyebæ, ifa nyešnye si.

exist-3 god spirit-pl-and human-pl none-and

There were gods and spirits, but no humans.

Fifihan fämnë mecat winyat.

Fifihan fæmnye mekat ʘinyat.

hab-work-3 spirit-pl foot-loc gods-pl-gen

The spirits worked for the gods.

Ninin ßaßal šalacbä, ifa çoçoin ®ony, ifa mimin.

Ninin šašal šalakbæ, ifa ʇɤʇɤin ǁɤny, ifa mimin.

hab-grow-3 junegrass knotcorn-and, and hab-dig-3 valley-pl and hab-sacrifice-3

They grew grain and dug river valleys and made sacrifices.

Loßan ifa on fiha.

Lɤšan ifa ɤn fiha.

tired-3 and stop-3 work

They were tired and stopped working.

Wcu mutil daš nyow mumin®.

ʘkɯ mɯtil daš nyɤʘ muminǁ.

3-go-3 god mind-loc know why vent-sacrifice-3-not

The gods came to them to see why they did not sacrifice.

Can fämnë, Loßas fiha.

Kan fæmnye, Lɤšas fiha.

say-3 spirit-pl / tired-1 work

“We are tired of working,” said the spirits.

Mes® çiçil mew? Ge-fihas® se.

Mesǁ ʇiʇil meʘ? Ge-fihasǁ se.

be-1-not child-2-pl Q / intent-work-not more

“Aren’t we your own children? We will not work any more.”

Gegen winy, ifa wcon® fämnyit dihnë.

Gegen ʘiny, ifa ʘkɤnǁ fæmnyit dihnye.

hab-talk-3 god-pl / and 3-exist-3-not spirit-pl-gen ear-pl

The gods talked and talked, but the spirits had no ears for them.

Can An ‰icam, ge-ça ufihnë nyuße, sfihal.

Kan An ǁikam, ge-ʇa ɯfihnye nyɯše, sfihal.

say-3 lady ocean / intent-make worker-pl sand-abl / 1-work-adj

An ǁikam said, “We will make workers from sand, to work for us.

Ceh ha-doman, ge-spoç nepe a® wit.

Keh ha-dɤman, ge-spɤʇ nepe aǁ ʘit.

however irr-live-3 / intent-1-give body dead god-gen

But to make them live, you must give me the dead body of a god.”

Ba®an wi Uhol®.

Baǁan ʘi Ɯhɤlǁ.

mid-kill-3 god one-see-not

The god Ɯhɤlǁ [The Blind One] was killed.

Men wi çlicat, ifa weh nyow con® wi çlicil.

Men ʘi ʇlikat, ifa ʘeh nyɤʘ kɤnǁ ʘi ʇlikil.

be-3 god Črek-gen / and that-one why exist-3-not god Črek-loc

He was the god of Črek, and this is why Črek has no god.

Çan nëßnë An ‰icam, ifa fifihan nëßnë mekat winyit.

ʇan nyešnye An ǁikam, ifa fifihan nyešnye mekat ʘinyat.

make-3 human-pl lady ocean / and hab-work-3 human-pl foot-loc god-pl-gen

An ǁikam made humans, and the humans worked for the gods.

Pupulyan ®onë nëßnë.

Pɯpɯlyan ǁɤnye nyešnye.

hab-fill-3 valley-pl human-pl

The humans filled the valleys.

Oçlil, pägain ®o nyany Nyaça ifa men wily.

ɤʇlil, pægain ǁɤ nyany Nyaʇa ifa men ʘily.

end-loc unite-3 valley all-pl Nyaʇa and be-3 queen

Finally Nyaʇa brought all the valleys together and became queen.

Goçan gä daßaçil ifa ba®an.

Gɤʇan gæ dašaʇil ifa baǁan.

rule-3 year hundred-loc / and mid-kill-3

She ruled for a hundred years, then died.

Ceh çeçeça nëßnë ifa mimin gapum, hoi cäcän wily çeçno.

Keh ʇeʇeʇa nyešnye ifa mimin gapɯm, hɤi kækæn ʘily ʇeʇnɤ.

however hab-noisy-3 human-pl and hab-sacrifice-3 not.enough / therefore hab-molest-3 god-pl noise-3

But the humans were noisy and did not sacrifice enough, and their noise bothered the gods.

Hoi gun çbedurnë mutil çen Íuç.

Hɤi gɯn ʇbedɯrnye mɯtil ʇen Šɯʇ.

therefore send-3 Verdurian-pl mind-loc destroy Šɯʇ

Therefore they sent the Verdurians to destroy Šɯʇ.

Bah nyow mocu.

Bah nyɤʘ mɤkɯ.

this-thing-3 why vent-2-go

This is why you (Verdurians) came.

(To come: a voice recording of part of this text.)

Basseta Lyai.Presumably because he’s speaking to a Verdurian, Lyai uses the Verdurian word for queen, elye (< elrei).

Basseta Lyai.

mid-1-name-3 Lyai

My name is Lyai.

Doma gä teha ely.

Dɤma gæ teha ely.

live-1 year 18 4

I’m 72 years old. (A round number in eighteens— he could be anywhere 72 or older.)

Ecac ow?

Ekak ɤʘ?

say-2 what

What did you say?

Cac ®ec, musoson® dih mui.

Kak ǁek, mɯsɤsɤnǁ dih mɯi.

say loud / vent-hab-good-3-not ear somewhat

Speak louder, I’m a little deaf.

Ge-cac nilunyä mew? weh nyow?

Ge-kak nilɯnyæt meʘ? ʘeh nyɤʘ?

intent-speak machine-allat Q / that why

I should speak to the machine? Why?

Lcon dihnë; con nilut dihnë mew?

Lkɤn dihnye; kɤn nilɯt dihnye meʘ?

2-exist-3 ear-pl / exist-3 machine-gen ear-pl Q

You have ears, does the machine have ears?

Sßän gi-ecac, nilu.

Sšæn gi-ekak, nilɯ.

1-say-3 intent-2-speak / machine

She asked me to speak to you, the machine.

Sɤl, kan®.

Sɤl, kanǁ.

good / say-3-not

Miss, It doesn’t say anything.

Con ®itil nilut ow?

Kɤn ǁitil nilɯt ɤʘ?

exist-3 heart-in machine-gen what

What is inside the machine?

Ai weh. Cocon elët nilut lyonë hopat bahat.

Ai ʘeh. Kɤkɤn elyet nilɯt lyɤnye hɤpat bahat.

oh that-thing / hab-exist-3 queen-gen machine many-pl face-gen this-thing-gen

Oh yes. The queen had many machines like this.

Word count: 503

ai interj oh, ooh, ah afa v blow; breathe afah n breath; breeze aly pr other, another; (answering a negative questiion) no, it did happen an n lady, chief, noblewoman anl a noble, high-born An ǁikam n the chief goddess [‘Lady Ocean’] aʘis n statue of a nude goddess, bringing blessings [Bh apsiś ‘nymph’] aǁ a dead æh interj ow, ugh ætaš n fox bah pr this one (inanimate) baly pr this -bæ afx comitative bæl n hand bedɯk n Verdurian language Bedɯr n Verduria [V] bepɯš n rifle, gun [V] besak n Wesaitan language Besat n Wesaita [Bh] beš v lose; (middle) be lost beših n loss biʇ n side, flank Bɤgat n Bhöɣeta Sea [Bh] Bɤhat n Bhohait (country) [Bh] bɤl n eye bɤla a guard, watch over; check, test; spy bɤǁ n rock, stone bɤǁl a rocky, stony bɯha n night dak n tree dalɯ n king (of Verduria) [V] daš v know dašaʇ # one hundred [Bh] daših n knowledge dek # ten [V] dæ a moral, right, virtuous dæh n morality, virtue dæf n dance dæfa v dance dæm n back dæml a posterior, in or at the back delæ n ash, ashes; soot; ink delæl a ashy; gray den n document, paper; relic [V] dih n ear; listening diʇ v hear, listen dɤm n life dɤma v live dɤsat n salmon dɯi n steam [V] dɯk n bean [Bh] dɯl v miss (not hit); fail; sin dɯǁ n failure; sin ebæs n condor (a bird of prey native to eastern Lebiscuri) ekak v you’re welcome (response to thanks); so you say, do tell [‘you say it’] eke # one third Eles n Eleď, Verdurian deity— in full ʘai Eles [V] ely # four elye n queen (of Verduria) [V] enyɤl v thank you [‘you are kind’] ep # seven [V] faba n breast fak n knot, binding faka v tie, bind; wear (i.e. tie on) fakah n skirt; clothing fala n coin, money (esp. Ereláean) [V fale] fæm n godling, minor deity, spirit [‘great spirit’] fæml a uncanny, fae; relating to godlings; name of a river fæt n soul, spirit fila n flower fih n work, toil fiha v work, toil fiʇ n blood fiʇl a bloody fɤt n door, gate; entrance fɤta v enter fɯl a light, white fɯm n silver [‘great white’] fɯna n apple [Bh] gai v make (someone do), cause gapa n tail gapɯm adv not enough [‘bad amount’] gasɤl adv enough [‘good amount’] gat n amount, sum; rate gæ n year gæl a tall, high ge pfx intentive prefix gep v talk, chat, converse (3s form gem) geʘ n conversation, chat geʘem v argue [gep-šem ‘talk hot’] gɤ v drink gɤh n drink gɤly n penis gɤm pr you gɤš n moss gɤʇ n head; capital (city); rule gɤʇa v rule, reign gɯ v send, cause to go gɯh n bottom, base; ground, floor gɯha v found, establish; (middle) be located gɯi n way, manner; path [related to ‘send’] gɯn n skin gɯp n dog haly n girl child, daughter han conj or ha pfx irrealis prefix had n line, row [Bh] hakak v whisper [imitative ha + ‘say’] han n field, yard Hanan n Hanuana he n temple hela a round, curved helah n ball; sphere heʘ n aunt (father’s sister only) heš v, n wash, clean hi # two higai v divide, cut In two higaih n division hik n companion, partner; husband hikat n father- or mother-in-law (of wife) hily n female companion; wife hilyat n father- or mother-in-law (of husband) hiʘɤ pr some his a fast, quick hisa v run hɤh n vision, looking, observation hɤi conj therefore, so hɤl v see, look at; habitual observe, watch hɤlǁ a blind, unseeing [‘not see’] hɤp n face, front hɤpl a frontal, in front hɯ v cry; mourn hɯh n tears; mourning hɯkal n coastal desert; the arid places between the valleys hɯm a old, aged; elder hɯmih n age ih a small, little ifa conj and, then, moreover iʇ n center, middle iʇl a central, middle kai adv less kak v speak, say kah n language, speech, speaking kap v hide, conceal; (middle) be hidden. 3s form is kam kæʘ v bother, molest, annoy Kebi n Kebri [K] kebik n Kebreni language keh conj however, but, in contrast kel n a Verdurian city [V ‘port’] ket a different, separate keta v separate; treat differently keʘ v, n drop; (middle) fall keǁ n sword kip a green kiʇ v steal, rob kɤ v exist; there is/are (existential verb) kɤba v gather, collect; fish kɤh n thread, string [Bh, with nominalizer] kɤla n oil [Bh] kɯ v go kɯh n road, route; departure kɯm n fire kɯna n money, coins [V] labah n lorbil, a type of squash [Bh] laš n storm lip v teach; counsel, advise; (middle) learn, study (3s form lim) lis v build, erect liʘ n teaching, education; advice, counsel lɤpih n song lɤpi v sing lɤš a tired lɤša v be tired, be worn out lɯk v run, manage, lead lɯka # twelve [Bh] lɯl b beard lyai n icëlan lyeh # ten lyes v have sex, make love; (n) sex lyika n star [Bh] lyɤ pr much, many lyɯ n hide; leather mah n milk maha v nurse (a baby); (middle) suck, be nursed mahl a milky; name of a river mai # half makak v moan, murmur [imitative ma + ‘say’] mal v sit; serve, work for malih n servant mašuh n beer, fermented drink mašuk v brew, ferment; (middle) be fermented [Bh ‘brewer’] mat n day; time

An Mat Ënomai, the Sunmatɤlat n winter [‘time of snow’] matmɤkat n birth, birthday [‘day of bearing’] matšemat n summer [‘time of heat’] maʇ n luster, shine maʇa v shine maǁ n gold [from ‘shine’] mæ a big, large mækak v shout [‘big say’] mæm v great, huge, enormous me v be; (as clitic) imperfective mek n foot; mekat X-(gen) for X, on X’s behalf meʇ n boy, son meǁ pt no [‘it is not’] meʘ pt question particle [‘be’ + interrogative] mida # nine [Bh] mih n sacrifice, worship mik v sacrifice (to gods), worship [Bh] Misæt n Mirzait [Bh] mɤ n water; river mɤgɤh n tavern, inn [‘place of drink’] mɤk v bear, give birth; (middle) be born mɤl a watery, liquid mɤly n sister (daughter of a pa) [‘born’ + fem.] mɤs n grandchild (child of a umɤ or mɤly) [‘born more’] mɯ v lie down, recline mɯbesat n shop, store [‘place of the Wesaitan’] mɯg a heavy, dense mɯi adv somewhat, a little, partly mɯil a partial; scanty mɯlip n school [‘place of learning’] mɯlyes n brothel [‘place of sex’] mɯpily n country, kingdom, queendom [‘place of queen’] mɯs n place, location, site mɯsa v put, place mɯš n worm, grub mɯt n liver; (metaphorically) mind, will; (loc) intending to, of a mind to mɯtl a willful, impulsive na n father, father’s brother nabir n ship [V] nak n edge, rim; shore, beach nal a urban, of or in the city nam n palace, mansion; court [‘big house’] naml a courtly, governmental nan a short nanɤt n grandfather (i.e. the na of any na) [‘father of father’] nap n house naǁ n city, town naʘ v show, draw attention to, cause to see næ v throw, cast næh n slingshot næp a wise; prudent næpih n wisdom, prudence nef # nine [V] nepe n body ne v sleep neh n sleep neš a previous, last neteǁ n viper, poisonous snake in the coastal valleys; slang for Verdurians neʇ n bee ni a young, new nih n opening, hole nil a feminine, female nilɯ n machine, device, contraption [V] nily n young woman, girl, maiden nim pr I nis v plant, sow, grow (tr.); farm; (middle) grow (intr.) niʘ n finger niʘa v touch; find, locate niǁ v open nɤ pt only, just, nothing but nɤf v desire, need, love nɤi n herb, weed nɤʘǁ n bitterleaf (ŋastwaśam) nɤnɤp n obsidian [from a western language] nɤǁ n seed, egg nɯh n pursuit, chase, hunting nɯi n cousin (see kinship section) nɯis n child of a cousin (see kinship section) nɯš v follow, chase; seek, search for; hunt; want to know nɯʘ n cod, a commonly caught fish nya pr each, every nyaʇ n thunder, lightning (they’re viewed as a combo) nyaʇa v thunder, strike (of lightning) Nyaʇa n the queen who conquered all of Šɯʇ [‘thunders’] nyaʇap # eight [Bh] nyaši # six [Bh] nyalɯ # seven [Bh] nyar # five [Bh] nyaš n bravery, boldness nyašl a brave, bold nyæk n garlic [Bh] nyæt afx allative nye a malignant, evil nyeh n evil, chaos nyek n earth, land; (pl) the world, Almea nyeš n human; person, individual; (pl) people nyešl a human, mortal nyih n lie, deception nyik n bug, insect nyily v lie, deceive (3s form nyiny) nyɤh a kind, generous nyɤša n fish nyɤʘ pr why, for what reason nyɯ n sand ɤmi n uncle (mother’s brother only); the son of any (ʇ)ɤmi ɤʘ pr who, what ɤʇ v stop, end, finish; (as prefix) stop (doing that)! ɤʇl n end, finish; (locative) finally, at last pa n mother or mother’s sister pal # four [V] pan # five [V] papɤt n grandmother (i.e the pa of any pa) [‘mother of mother’] pæ # one pægai v unite, bring together [‘make one’] pægaih n unity pæš n bresh, a plant producing a fabric like cotton [Bh] pely n cat piri v tell, recount pirih n story, tale pɤk n flauk (large lagomorph) [Bh] pɤp n leg; walk pɤpa v walk pɤš n fat, grease pɤšl a fat, fatty pɤʇ v give pɯly a full, filled pɯlya v fill; (middle) intr. pɯm a bad; sick, ill pɯt n sauce, cream; any viscous liquid pɯtl a creamy, viscous pɯǁ a foolish, stupid pɯǁa v act foolish, make a dumb mistake sai a early; ancient sak v heal, cure; care for; middle get better salat n arrow [Bh] saša n ease, relief; peace sašaly n whore, prostitute [‘ease woman’] se adv more ses # six [V] sesɯn n ktuvok [Hanuanan] set n name seta v name (someone), call; (middle) be named si pr none, not any sih n food; meal sil n, a hair; hairy siny a beautiful, lovely ssǁ interj hoy! hello! sɤl a good sɯm n bone; tooth sʘ v fry; cook, prepare food [imitative] šalak n knotcorn [Bh] šap n frog; drunk, high; (verb) be drunk— 3s is šam šašal n junegrass [Bh] sašur n Šočyan governor [V] šæh n request; beg; prayer šæha v ask, request; pray šæla n oasis, spring šæm n smoke šæml n smoky šæp n a peachlike fruit; an Ereláean (because of the skin color) šæs a dark; brown, black; a river -še afx ablative šel n sky šem n heat; the south šeml a hot; southern šeǁ v expect, wait for, hope šif v eat šil a male, masculine šim n young man, youth šiš a cold; northern šiših n cold; the north šɤ a long Šɤ n a river valley [‘long’] šɤk # eight [V] šɤm n blue Šɯk n the language of Šɯʇ Šɯʇ n the people or nation of Šɯʇ (Šočya), or of the Šɤ valley [‘of Šɤ’] tam v call, summon tat n thing, object, item teha # eighteen [Bh] tenaʇ # 324 (182) [Bh] titɯ n bird tɤk n rod, staff tɤka v strike, beat tɤl n/v snow tɯh n war, fight tɯl v fight, go to war tɯm n mountain; (in pl) the mountains west of Šɯʇ; the west tɯml n western; mountainous ɯbaly pr this one (animate) ɯbalip n student ɯbɤl n guard; spy ɯda n flour [Bh] ɯfih n worker; commoner ɯɤgɤly n tavern-keeper (usually female) ɯhɤl n watcher, observer; herdsman ɯhɤlǁ n blind person ɯhɯkal n scavenger, esp. someone who hunts in the coastal desert (hɯkal) ɯkiʇ n thief, robber ɯkɤba n fisherman ɯlip n teacher; counselor, advisor ɯlɤpi n singer ɯlɯk n leader, manager ɯlyes n lover, sex partner ɯly a holy, sacred, numinous; name of a river ɯlyɤ v live in, reside, inhabit ɯmal n servant, esp. male ɯmaly n maid, maidservant ɯmašuk n brewer ɯmɤ n brother (son of a pa) [‘one born’] ɯna n nose ɯnan n elcar [‘short one’] ɯnæ n peltast, slingshotter ɯnæp n wise person, sage ɯnis n farmer, peasant ɯnyeh n villain [‘evil one’] ɯpe pr that one (animate) ɯpɯǁ n fool, idiot ɯsai n ancestor ɯsak n healer, physician; caregiver ɯsalat n bowman, archer ɯsiny n a beauty, a beautiful girl/boy ɯsʘ n cook ɯš n forest, woods ɯšap n drunkard ɯšæh n beggar ɯšɤm n iliu [‘blue one’] ɯtɯl n fighter, warrior, soldier ɯš n egg ɯʇa n shaper; potter ɯǁe n commander ʘ pt yes! (short for ʘeh); as prefix, forms nominalizations and fractions ʘai n lord, nobleman ʘai Ɯʇa n consort of An ǁikam ; former chief god [‘Lord Shaper’] ʘæʘ a insane, crazy ʘæʘih n insanity, madness ʘdakat n wood [‘that of the tree’] ʘe pr that (demonstrative) ʘeh pr that one (inanimate); (answering a question) yes ʘelyat # quarter, one fourth ʘeš v fear, be afraid ʘgɤlyat n semen [‘that of the penis’] ʘgɯl n cargo, merchandise [‘that sent’] ʘha n lip ʘhanet n peach [‘thing of Hanuana’] ʘi n god ʘil a divine, godly ʘily n goddess; queen ʘilyat n the capital of Šɯʇ (Verd. Bílët) [‘(city) of the queen’] ʘilyni n princess, heir to the throne [‘new queen’] ʘisa n strong; last queen of Šɯʇ (to the Verdurians, Bisa) ʘlis n building ʘlyɯ n bag, sack [‘that of leather’] ʘket n tongue [‘that of speaking’] ʘmidet n one ninth; tax ʘneʇat n honey [‘that of the bee’] ʘnyarat # one fifth ʘnyit n monster [‘that of evil’] ʘšæs n coal, charcoal [‘that black’] ʘɤ # three ʘɤk a free, independent; (physically) loose ʘɤka v free; loosen ʘɤml a slow; a river ʘpɤpat n loincloth [‘that of the leg’] ʘɯm n mouth ʘɯt v subdue, (middle) abase oneself, bow down ʘɯtl a subdued; abased, humble, poor ʘʇɤi n mine, dig, excavation [‘that of mining’] ʘǁ a bitter, sour ʇ p son or daughter of ʇ- pfx member, individual with a characteristic [‘child’] ʇa v shape, form; create (as a god) ʇah n shape, form; creation ʇak n a river valley, south of Šɤ ʇala n homosexual [Bh caura] tæh n husk, peel ʇæk v peel, dehusk; strip (clothes); (middle) be naked ʇækl n peeled, dehusked; nude, naked ʇbedɯr n Verdurian ʇbɯha n moon [‘child of night’]

An ʇbɯha Iliažë, the larger moon [‘Lady Moon’]

ʘai ʇbɯha Iliacáš, the medium moon [‘Lord Moon’]ʇbɯhaih n Naunai, the smallest moon [‘small moon’] ʇe n priest, priestess [‘child of temple’] ʇeš v destroy, break ʇeʇ a noisy ʇeʇa v be noisy, make a ruckus ʇfæm n seer, oracle, prophet [‘child of godling’] ʇiʇi n child ʇlik n Črek, a nation and people north of Šɯʇ ʇnam n courtier, member of the court ʇnaǁ n resident of a city; citizen, townsman ʇɤh v, n cough ʇpily n subject of the queen, inhabitant of (greater) Šɯʇ [‘child of queen’] ʇsǁ n the masses, the commoners [‘people who say ssǁ’] ʇšɤ n inhabitant of the Šɤ valley ʇɤi v scratch; dig, mine ʇɤmi n cousin (daughter of ɤmi); the daughter of any (ʇ)ɤmi ʇɯny n pot ʇʇ v, n rain ʇʇlik n someone from Črek ǁ afx negative; standalone word don’t! no! ǁat v kill; middle die ǁe v command, order ǁek a loud ǁika n sea, ocean; the east; second queen of Šɯʇ ǁikal a eastern ǁikam n the Ocean surrounding the world ǁim n dung, feces, shit ǁit n heart; (metaphorically) vigor, guts; insides ǁitl n vigorous; a chief of ʇak [‘heartful’] ǁɤ n river valley ǁɯly n vulva, vagina [related to ‘valley’]