Jeerio tries to find a job

I originally wrote and illustrated this in sixth grade. It’s been

lightly revised; it was almost but not quite presentable as is.

(If you're curious, I did use words like 'inexorable' when I was 11.)

In the land of flaids there lived a promising young man, Jeerio by name, who was interested in Alchemy and Logarithms and Sailing Ships and Chronometers, and everything else a young flaid should be interested in, and more.

He lived in his Mom’s house

in lower Flaid Land, and when his mother told him she was fed up with his sleeping all day, and napping all night, and said he was getting too big for his desk, and really ought to go out and seek a living, why then Jeerio was terribly sorry, for you see, he liked sleeping.

He knew that packing for a trip was important, so he took with him four books on Alchemy, four books on Logarithms, four books on Sailing Ships, and three books on Chronometers, because he couldn’t find a fourth. He knew he would have to eat, so he took a flask of water, ten sandwiches left over from lunch, and fourteen salami rolls. He had not been gone for ten minutes, before he returned and picked up his umbrella, a change of underwear, a soup pot and a packet of spices, two mugs with pictures of monsters on them, and his pillow.

He thought for a minute, and added a folding chair, a thick pad of paper, at least twice as many pencils as he’d possibly need, and a pencil eraser.

His pet poodle, Twain, was not forgotten. He was to trail along.

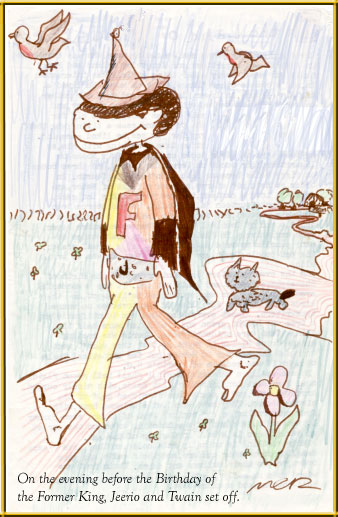

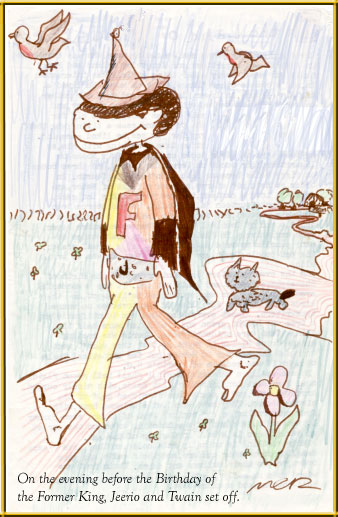

On the evening before the Birthday of the Former King, Jeerio and Twain set off. It was a wonderful evening, and the sun was setting, as it so often does, and the birds were singing in the trees—polkas and waltzes, mostly. The trees were bright and green, and there were bright colored flowers on the grass, and very often a squirrel or a rabbit scampered by. Jeerio felt that anything could happen—a job or an entire adventure.

They met very few other flaids.

Perhaps they didn’t want to get in the way of the view, or perhaps, as Twain believed, Jeerio should take a bath more often.

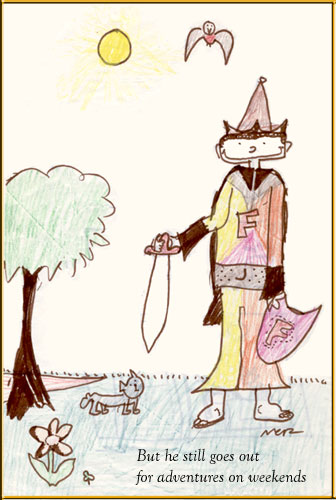

I should tell you something about

flaids. They are taller than human beings, with very big, flat heads. They have small eyes and very large mouths, which fortunately are usually smiling. Jeerio wore a tall conical hat with a bell on the top and a turned-up brim, a shirt and pants in very different colors, a cape, and no shoes on his very large feet. None of this was at all unusual for a flaid, although Jeerio felt that his hat was taller and finer than other flaids’ hats.

It was late in the evening when Jeerio decided to pitch camp, near a burbling stream. He had been walking without stop for many hours, and he was quite tired. Twain was also tired, and said so. Dogs, cats, and many other animals can talk in Flaid Land. They might be

able to talk here if they tried harder, which they usually don’t.

It was late in the evening when Jeerio decided to pitch camp, near a burbling stream. He had been walking without stop for many hours, and he was quite tired. Twain was also tired, and said so. Dogs, cats, and many other animals can talk in Flaid Land. They might be

able to talk here if they tried harder, which they usually don’t.

“How far do you think

we’ve gone?” asked Jeerio, as he set up the folding chair.

“I bet we’ve gone

halfway through Flaid Land,” answered Twain.

“I’m going to make

soup,” said Jeerio.

Jeerio gathered water from the burbling stream, and looked around for ingredients he could add to his soup. He found some chillee plants, which are something like lettuce but spicy, and some bird’s eggs, and put those in the pot, along with some salami, the packet of spices, and a sandwich. He built a fire and boiled the soup over it. He thought of adding a lizard’s eye and some bat wings, but that might render the soup poisonous, and even create a magic spell, once he recited:

Bubble,

bubble, toil and trouble,

Fire

burn and cauldron bubble.

He had learned about that sort of

thing in his Alchemy books.

He laid down on the grass, waiting

for the soup to be done, and read aloud from one of his books on Alchemy.

“Chapter one. Theory,”

he read.

Twain squirmed.

“‘Alchemy is the art

of making substances into other substances; while Higher Alchemy is the art of finding the Primordial Matter.

“‘Here is an interesting experiment in Alchemy. Take a triple-X flask of water, heat it over a flame of sodium, and add ammonia, lye, parsley, fingernail scrapings, naphtha, and orpiment. Cover the flask, distill for three hours, and heat the distillate, which will be a bright neon brown. Shout “Pyrzqzyl” over the roaring flames, and the distillate will ooze up, assuming the color of bread mold, take on a variety of shapes, and finally splash gaily onto your desk.’

“I think I’ll try that,” he remarked. “Don’t you think I should?”

“I think you should tend to

the soup,” said Twain.

Jeerio looked at the soup. It was done. He served it into the monster mugs, one for himself and one for Twain. I don’t think you would have liked it—perhaps Jeerio should have washed the eggs first, and taken the bread off the sandwich—but the flavor was certainly rich and interesting.

Jeerio cleaned up the pot and the mugs afterward—his mother could not do this, because she was back home—and went to bed, yawning dreadfully.

In the morning, they had scarely been on the road for an hour before they came upon a Dragon. Dragons are common enough in Flaid Land; this one was the size of a small house, perhaps a bungalow, with shiny scaly skin like a snake, batlike wings, fiery eyes, a horn on his head, and a row of sharp spikes down his back. He was bright green. When he breathed, hot steam came out of his nostrils.

“Oh, hello,” said

Jeerio cheerfully. “I presume you are a Plundering Pyrosaur?”

“I am that which you

say,” said the dragon, speaking haughtily, as dragons do.

“What’s your

name?”

“Carnivorous Unanimous the

Twenty-third.”

“Carnivorous Unanimous the

Twenty-third.”

“Oh. I’m

Jeerio.”.

Carnivorous Unanimous the

Twenty-third grinned, showing a large number of sharp teeth, each with valuable

gold fillings.

“What brings you out so

early, so early in the morning?” asked the dragon, in a sort of mocking sing-song.

“I am searching for an

occupation,” said Jeerio.

“An occupation? Is that the

name for that beastly gray animal?”

“I’m not a beastly

animal, I’m a dog,” said Twain.

“It can speak!” said

Carnivorous, as if surprised. “What’s your name?”

“Twain,” replied

Twain. “And I come of a high imperial lineage. I date back to St.

George’s poodle.”

“I date back to St.

George’s dragon and farther,” said Carnivorous.

“How far?” asked

Jeerio.

“To Arlemange of the Burning

Mesa of the Barbarian Plains,” replied Carnivorous.

“What does that mean?” asked Twain.

“I don’t know,”

said the dragon.

Perhaps it felt embarrassed by

this answer, because it paused to clean its back paws. It did this by

breathing fire on them, burning off anything that shouldn’t be there.

“Sorry to go—”

began Jeerio.

“Oh, I can’t let you

go,” interrupted Carnivorous. “It would be totally against the

rules of Dragonry! Think of what Arlemange would say!”

“I must go,” objected

Jeerio. And he walked boldly forward.

“No!” protested

Carnivorous, and he aimed a blow at Jeerio’s flat head. “I guard

the castle of Burntup the magician, and I am under very strict orders not to

let a flaid, human, iliu, or even an Ant to cross! If I disobeyed, I’d

be painted blue!”

“What’s wrong with

that?” asked Twain.

“Would you like to be

painted blue?”

“Certainly not.”

“Then you know how I

feel,” said Carnivorous, and shuddered.

There was a lull in the

conversation. No one knew exactly what to say. Jeerio’s mother had

taught him things to say to strangers, such as “What is your name?”

or “What do you do for a living?” or “There has been a lot of

trouble with dragons lately, hasn’t there?” But he already knew

the answer to the first two questions, and the third one did not seem polite.

Jeerio sighed. “How am I

going to find a job,” he said reproachfully, “if I can’t

venture on?”

“I know, I know,” said the dragon. “A lot of people try to touch my conscience or my good nature, but I’m much too afraid of being painted blue to worry about things like that. I’m very sorry, but Burntup won’t allow it. Please, go another way. I’m getting a sore throat.”

“Drink from the moat,”

suggested Jeerio.

“I know that

trick,”said Carnivorous. “When I’m gone, you’ll zip

by, and I’ll get painted. Nothing doing. Go the other way; it goes to

Syxesteer. Flaids there, too. But you mustn’t come this way.”

“Oh, all right,” said

Jeerio.

“Where does the road go on

from there?” asked Twain.

“It goes everywhere in the

world,” said Carnivorous.

Twain supposed that this was a

riddle. Jeerio’s riddles were mostly about grapes, or Alchemy, and so

Twain preferred not to try to guess it.

Jeerio and Twain took the road to

Syxesteer.

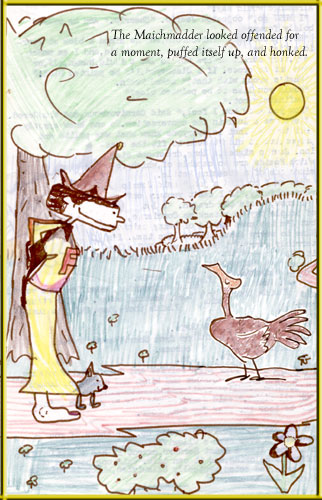

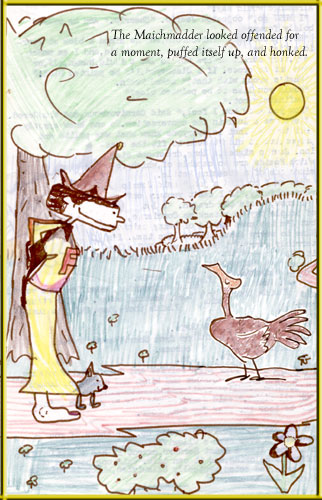

Not much further on, they came upon a large brown bird, which was hopping about on the grass. Very often it would stop, puff out its chest, and make a sort of honking burping sound. It was bigger than a chicken, and looked twice as large as it was, with a tail-fan of long brown feathers it held proudly out.

Jeerio and Twain stopped to watch it. It continued hopping around and burping.

“Can you talk?” Jeerio asked it. “If not, I think you might make a good dinner.”

“I can talk, I can

talk,” said the bird, and honked once more.

“You can say ‘I can

talk,’ but maybe you can’t actually talk,” suggested

Twain.

“I can talk,” insisted the bird; but Twain still looked skeptical.

“If you can talk, what are

you?” asked Jeerio.

“I am a Maichmadder,”

said the bird. “I am by far the most important bird for at least a hundred feet around.”

Jeerio and Twain looked around,

but didn’t see any birds closer than that anyway. They had to admit,

however, that the Maichmadder looked very important.

“Why do you honk like

that?” asked Jeerio. “Are you sick?”

The Maichmadder looked offended

for a moment, puffed itself up, and honked. “My call is a signal,” it explained. “The meaning of the signal is that I am by far the most important bird in this area.”

“There aren’t any

other birds here,” said Twain.

“That is because they have

understood the signal,” said the Maichmadder.

“What do you do for a

living?” asked Jeerio.

“I eat insects,” said

the bird. “However, I do this to support myself. My primary purpose is to be the most important bird in this area. In fact,” it added, with a honk-burp, “you shouldn’t be here.”

“Why not?”

“This is my area, and no

other birds are allowed here.”

“I’m not a bird,

I’m a flaid,” said Jeerio.

“I’m not either, but I

am a dog, and a hungry one,” added Twain.

The Maichmadder turned its head

sideways and looked at them, then turned its head the other way and looked at them again.

“Very well,” it said.

“As you are not birds, you may stay here for a time. However, you must tell me, as the most important bird in this area, what you are doing

here.”

“I’m walking on the

road,” said Jeerio.

“You are seeking

adventure?” asked the bird.

“Yes, that’s

it,” said Jeerio, thinking that the bird was more intelligent than he had

thought.

“You have no

equipment,” said the Maichmadder.

“I do! I have books, and a

soup pot, and a pillow, and all sorts of things!”

“My dear flaid, for an

adventure you need a sword and a shield. These are required to fight the

fierce enemies you will meet.”

Jeerio was inclined to argue with this, but he was worried that the Maichmadder might be right. People sometimes started off an adventure without a sword, but sooner or later it seemed that they needed one.

“Do you know where I can get

one?” he asked.

“I have checked this area

thoroughly, and have not seen even one,” said the bird. “If there

were one here, I would know about it.”

It puffed out its chest and honked

again.

“In that case, we’ll

have to keep on,” said Jeerio. “Goodbye.”

“Goodbye,” said the

bird. “If you find another Maichmadder—a female Maichmadder, mind

you—you may invite her to my area.”

Jeerio promised to do so, and they

travelled on.

“I wish he had been

dinner,” said Twain. “Do you think you’ll get a shield and

sword?”

“What do you think?”

“No,” replied Twain.

“Aren’t you looking for a job?”

“Of course, but I’m

looking for adventure, too.”

“If you get a job, how can

you go on adventures? Where would you put your shield and sword?”

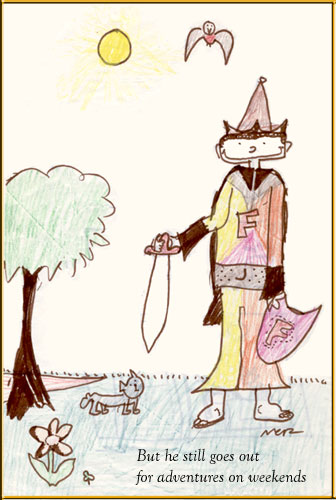

“I could look for adventures on weekends,” Jeerio pointed out. “I could find some Dwarfs—they always have adventures to share—or an evil wizard, or a medium-sized monster, one that I could vanquish in a weekend.”

Twain looked a little disapproving. There was a long silence, during which they walked on, and each thought their own thoughts, which they had found was a good deal easier than thinking each other’s thoughts.

Each of them was thinking of good arguments to prove their point. When they went over them in their heads, each of them found their words inexorable, which means that the other would simply have to give in immediately. However, when they stopped for dinner, instead of having an argument they had dinner. So we will never know if their words were inexorable or not.

The next day Jeerio kept his eye out for swords, or for Maichmadders. But this was soon forgotten, when Syxesteer was spotted.

The next day Jeerio kept his eye out for swords, or for Maichmadders. But this was soon forgotten, when Syxesteer was spotted.

Syxesteer was a very large city,

with elaborate buildings painted blue or red or orange. The houses were tall, so that the street was in shadow; perhaps because of this, there were lanterns set on iron lampposts all along the street. Their road was colored red and the other streets were black, so that you could easily follow it without getting lost.

The city was full of flaids—flaid children playing games or doing their homework or delivering newspapers, flaid adults watching the children, or riding horses, or buying things, or talking to each other about all sorts of things. They were friendly, as well; Jeerio soon knew ten or fifteen young flaids; and Twain had met even more dogs, most of which became his friends, because of his pleasant disposition.

Between meetings with dogs, Twain

busied himself counting houses. 176 houses since the sign with the name of the city on it, they came to the downtown area. He and Jeerio had never so many stores, offices, and important-looking buildings. Businessmen, businesswomen,and businesschildren rushed by busily on business. Boys rode by on bicycles, or tricycles, or even quadricycles and quinticycles. Dogs rushed by after cats; cats ran by before dogs. There were even short, small-headed people with big clumping boots. Jeerio stared at them because he had never seen a human before. If one of them was you, he didn’t mean to stare like that and would like to apologize.

The red road ended at the water, because Syxesteer was on the ocean. Beyond the city was blue water as far as they could see, with hundreds of ships and boats.

It struck Jeerio that he should take a boat ride. He rushed up to a flaid who was tying a boat to a dock, and asked if he could buy his boat.

“Do you have any

money?” asked the man.

As it happened Jeerio had received

a large silver coin for the Former King’s Birthday. Flaids like to give presents on the King’s Birthday, and they saw no reason to stop when they found they had no more kings. The coin was called a meckin, and it was worth about ten dollars, or maybe eleven.

He showed the coin to the man.

“It’s not enough for a

boat,” the man said. “But old Jijo rents boats, and good ones; there he is, you can talk to him.”

So Jeerio went to see old Jijo, and asked if he could rent a boat for his large silver coin. Fortunately, old Jijo was a friendly old flaid, and he took a liking to this promising young flaid, who seemed to be interested in Alchemy and Logarithms and everything a flaid should be interested in.

He showed Jeerio a serov, which is a small sailboat with room for one flaid and a dog. Old Jijo showed Jeerio how to pilot it; Jeerio learned quickly because he had read four books on Sailing Ships.

When Jeerio thought he was ready, he cast off, and he and Twain sailed away from Syxesteer. It was a beautiful day, and the breeze blew the boat’s flag forward. You might expect that the flag would point backward, but on a sailboat the flag points where the wind is blowing.

I suppose I really should finish this story up and let Jeerio have a job. You all probably want to read something else.

Jeerio piloted the boat for the rest of the day, and when they had slept he started up again. There weren’t any storms, or monsters, or seasickness, or collisions—it was all very pleasant. Twain was worried about falling off, or getting hit in the head by the sail, but the worst that happened was that his eyes got bloodshot from the salt in the air.

Imagine Jeerio’s feelings when Twain shouted, “Land ho!” He carefully sailed to shore, feeling quite adventuresome. He was eager to explore this new land.

It turned out to be an awful waste. The boat had made a big circle, and the adventurers were back in Syxesteer. They returned the boat to old Jijo, and walked disconsolately through the streets, following the red road, past the area where the important bird lived, past the dragon—not saying a word, because they were so disappointed in their sea journey. Finally they arrived back at his mother’s house, where they ate a fine meal.

It turned out to be an awful waste. The boat had made a big circle, and the adventurers were back in Syxesteer. They returned the boat to old Jijo, and walked disconsolately through the streets, following the red road, past the area where the important bird lived, past the dragon—not saying a word, because they were so disappointed in their sea journey. Finally they arrived back at his mother’s house, where they ate a fine meal.

“How was your trip?”

asked Jeerio’s Mom.

“Fine,” said Jeerio.

“What went wrong?” she

asked.

“Our sea journey,”

said Jeerio.

“I think your land journey

went askew,” she answered. “Why didn’t you go to the

restaurant half a mile down the road from here? It needs a waiter.”

“Why, that’s not a bad

idea! I will!” said Jeerio, brightening up.

He kissed his Mom goodbye, and

went to the nearby town, Pickapo, where he applied for the waiter job at the restaurant.

“It’s very

strange,” he thought, “that I took such a long trip, when there was a job right next door in Pickapo.”

Jeerio is still working at the restaurant, taking orders, collecting money, cleaning pots and pans, giving coffee to anyone who wants it and some who don’t, wiping off the tables, writing out the menu, eating extra desserts, cooking the beef bourguignon, chasing down people who don’t want to pay, and all that.

But he still goes out for adventures on weekends.

It was late in the evening when Jeerio decided to pitch camp, near a burbling stream. He had been walking without stop for many hours, and he was quite tired. Twain was also tired, and said so. Dogs, cats, and many other animals can talk in Flaid Land. They might be

able to talk here if they tried harder, which they usually don’t.

It was late in the evening when Jeerio decided to pitch camp, near a burbling stream. He had been walking without stop for many hours, and he was quite tired. Twain was also tired, and said so. Dogs, cats, and many other animals can talk in Flaid Land. They might be

able to talk here if they tried harder, which they usually don’t.

“Carnivorous Unanimous the

Twenty-third.”

“Carnivorous Unanimous the

Twenty-third.”

The next day Jeerio kept his eye out for swords, or for Maichmadders. But this was soon forgotten, when Syxesteer was spotted.

The next day Jeerio kept his eye out for swords, or for Maichmadders. But this was soon forgotten, when Syxesteer was spotted. It turned out to be an awful waste. The boat had made a big circle, and the adventurers were back in Syxesteer. They returned the boat to old Jijo, and walked disconsolately through the streets, following the red road, past the area where the important bird lived, past the dragon—not saying a word, because they were so disappointed in their sea journey. Finally they arrived back at his mother’s house, where they ate a fine meal.

It turned out to be an awful waste. The boat had made a big circle, and the adventurers were back in Syxesteer. They returned the boat to old Jijo, and walked disconsolately through the streets, following the red road, past the area where the important bird lived, past the dragon—not saying a word, because they were so disappointed in their sea journey. Finally they arrived back at his mother’s house, where they ate a fine meal.